By Miki Kashtan

Part 2: Realigning Education and Systems with Life

In the first part of this article I spoke about the maternal gifting paradigm as an understanding of our evolution into what Humberto Maturana calls a “biology of love” lineage, which has then shaped us socially to be what Genevieve Vaughan calls a “mothering species,” where both the capacity to orient unilaterally to others’ needs and the capacity for ongoing social collaboration are essential for our survival. This framework is at odds with mainstream theories of human nature that orient from within the patriarchal mindset of scarcity, separation, and powerlessness and put competition at the center of theory and practice.

I also spoke of the four spheres that make up any social structure and support the reproduction of any social order: social institutions, education and socialization, human behavior, and “the story,” otherwise known as theories of human nature. One of my key points in that first part is that this is true of all social orders, whether they are aligned with life and maternal gifting principles, or whether they are aligned with patriarchal principles. This also means that any attempt to transform any social order — such as many of us are calling for in order to create a livable future on Earth — would also need to touch in some way on the four spheres as a way to reduce the chances of efforts for change being reabsorbed into the existing social order.

What is ours to do

At a talk I gave at the Re-imagining Education Conference from which this article emerged, I was asked a particularly harrowing question by a person from India about the system of education there. Given the deep and thick links between schools and the totality of the colonial and ostensibly postcolonial social order, I am painfully aware of just how far we are, collectively, from being able to influence systems at the level that could result in making a dent in the lives of billions of children.

And yet, as I shared with the person on that talk, we all want to act. How, then, do we find a path within what I described here that has integrity and meaning? One of the key lessons that I have learned over decades of experiences is that we can find that compass when we focus only on what is within our sphere of influence rather than preoccupying ourselves with all the changes that “must” happen about which we can’t do anything.

Without knowing the circumstances of the person, I could only imagine a scenario. For example, if she had a child in a school setting that is similar to what she described in her question, it is within her sphere of influence to engage with a teacher in dialogue oriented to caring for both the teacher and the child. And if that works out, the next thing may be talking with the principal and supporting change in how teacher meetings are run. The essential principle is that regardless of how big or small our sphere of influence, we take the most radical steps we can towards the maternal gifting way of life.

This, in essence, is what we do within the Nonviolent Global Liberation (NGL) community. We are not working on the large scale of how we change things, because we literally don’t have the capacity to do that. Instead, what we focus on is deep experimentation that reveals to us patterns and ways of functioning that may serve as blueprints for others in what they are doing. Whatever we learn we then share with others, which means that the sphere of learning and education is itself an area of experimentation within our work, one of about thirty different experiments within how we function.

Although our experiments touch on all four spheres of social functioning that I have introduced in the first part of this article, in the rest of the article I am focusing primarily on the application of maternal gifting principles in two of the four areas: “education and socialization” and “social institutions.” At the same time, given how deeply interrelated everything is, our experiments by necessity also touch on “the story” and on “human behavior.”

In this part of the article I am focusing primarily on the larger principles we have both uncovered and leaned on in our work. In the third and last part of the article I am taking a closer look at the actual experimentation. Within that part I present two case studies that illustrate what can actually be done, right here and right now, to align with maternal gifting. The case studies also illustrate the intertwined nature of all four spheres, since so many of our experiments overlap with other experiments and span more than one area.

Lessons from educational giants

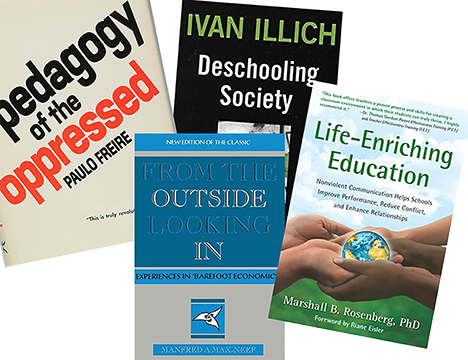

In addition to the deep focus on maternal gifting, our work within NGL includes an attempt to walk in the footsteps of educational visionaries Paulo Freire (Pedagogy of the Oppressed), Ivan Illich (Deschooling Society), Marshall Rosenberg (Life-Enriching Education), and Manfred Max-Neef (From the Outside Looking in). In different ways they each engaged in deep experimentation about what supports both learning and teaching to be voluntary and collaborative activities oriented to the needs and capacities of all involved. This focus, and orienting to people of all ages, puts them all at odds with the general direction that education and schooling have taken.

Like so many thinkers and practitioners whose work aligns with life, their work is pointing in the direction of vision and offers specific principles, practices, and processes that support the journey. Within NGL we have been engaging with six key shifts that I see within their work. I am not surprised to see how much the “to” part of each of these shifts is also aligned with the organizing principles of maternal gifting, even though to the best of my knowledge none of them knew about it. I am illustrating each of them with some reflections about what we do within NGL and about what else may be possible.

From knowledge consumption to knowledge co-creation.

Our teaching tends to be dialogical and participatory. For example, twice a week, we have times when people come together to engage with Learning Packets that I have put together to share the learning from our current experimentation and my previous work. Instead of coming to listen to me and take in knowledge, these two hours provide two ways for people to participate in creating the knowledge. For the first hour, I am not there; people study on their own. For the second hour, I or sometimes someone else comes to answer questions, and we invite those present to be the first ones to answer any question before we do, so that they engage with the content in a way that their capacity and leadership can increase. More deeply, my own thinking is shaped, in part, by what others say, and that, too, is part of knowledge co-creation.

Knowledge co-creation is one way we can exit the “banking model” of education. We also can antidote it with mutual feedback. This means that students give feedback to teachers in addition to teachers giving feedback to students. This makes all of us human together, all of us learning and teaching in different measures. There is a Talmudic saying: “I have learned from all my teachers, and more than anything I have learned from my students.” Knowledge co-creation and mutual feedback don’t necessarily mean we are all in the same place, only that we are all actively contributing to the learning as full human beings no matter our age, our knowledge, our capacity, or our social location.

From control and “power over” to natural authority.

It rarely happens among us in NGL that decisions about anyone’s learning and access are made by others. Simultaneously, we give more weight to the perspective of those who are carrying the lineage within which we are working — who, in part, find themselves there because others have noticed their authority, maybe even before they themselves reached that level of self-trust. In this way we are reviving the ancient path of power that is based on natural authority. Within this approach, there is no expectation that carries any potential punitive consequences that anyone would do something just because someone “in authority” says so. Instead, we all attempt to embody qualities, experience, and knowledge that would naturally generate trust and respect in others so that they would want to hear from us. We have taken in fully that forcing anyone to listen or do something doesn’t help learning.

This focus on orienting to leadership based on natural authority, trust, and collaboration goes beyond education within our community. Both in learning and in how we function overall, our approach to leadership is an alternative both to top-down, command-and-control patriarchal functioning and to the anti-authoritarian reactions that insist that leadership isn’t necessary. We call this “co-creation within a led field,” and some of us believe that our practices may be uncovering deep aspects of being human that have been kept intact within some Indigenous societies and fully submerged within patriarchal societies. This capacity is essential for experimentation in how to support learning within and beyond our community.

From standardized curriculum to needs-based learning.

We have been experimenting more and more with supporting each person who joins our core learning programs to create their own learning journey based on their needs and capacity as well as a sense of what is needed within NGL as a whole. Similarly, in our courses and other offerings, we respond to each person according to where we sense they are in terms of their integration of what we are sharing at any given moment. We also attempt to orient, even in the moment, to what each individual we engage with may need to learn, and overall to structure our offerings to attend to various needs, not just one set of needs.

For example, we may offer different kinds of breakout activities for different learning purposes: In one of my courses I arrange a facilitation debrief for those who want to learn about facilitation while others continue in breakout groups; and we invite specific people who have indicated a desire to apprentice in particular areas to be primary participants in certain courses while others are invited to observe and ask questions at the end.

Orienting to needs also supports us in antidoting the false either/or in which the only alternative to coercive education is “free-for-all.” I don’t actually believe that free for all is a coherent educational system that can support learning and liberation. Orienting to actual needs, for everyone, brings to the foreground the variability of who we each are, the uniqueness of our capacities, and the irreducible reality that almost nothing will work for everyone in the same way. That’s when we start doing the hard work of integrating across differences and finding pathways to care for everyone’s needs.

From obedience to critical thinking.

|Despite the commitment to humility that we come back to again and again, whenever any of us are perceived as the “teacher” in any given context, pervasive disempowerment may lead people to believe that they are simply expected to agree with what we say. It takes ongoing attention to notice when this happens and to counter it with invitations to question everything, including what we ourselves say when we teach. At the same time, we stress deeply how vital it is for the questioning to happen from within trust and connection so that we can stay in togetherness as we seek knowledge. Our goal is for people to learn to think for themselves, to question systems, and to question what is happening within them, around them, and in the world at large.

As part of this we have adopted a profound and radical principle within NGL, which is that people do things only if they find true willingness. We see this as antidoting the reproduction of the social order through obedience. This applies, also, in our approach to engaging with children of any age.

I have anguish that I carry with me from a time when I led a training for a group of teachers within a public school in the USA. I asked them a simple question: “What needs of the children who come to school every day do you see yourselves responsible for caring for?” Their responses covered a wide range of needs in the areas of physical needs, connection, and meaning. Even with all the depth of caring I sensed in that group, there was still no mention of a hugely significant area of needs for all humans and all living beings for that matter: freedom.

Put bluntly, they didn’t see themselves in any way responsible for supporting the children to develop their capacity for choice and to have freedom. This, to me, is a symptom of the degree to which obedience is a core goal of so many educational systems.

What I want, instead, is that every bit of everything that anyone, of any age, will do is done only from true choice and willingness, not from coercion, shame, fear, “have to,” “should do,” duty, or obligation.

From shaming to deep self-trust.

One of the challenges of a post-patriarchal approach to teaching and learning is how to provide feedback to those whose focus within the setting is primarily on learning. The challenge is how to circumvent the deep groove of shame that so many of us are familiar with from our years in the school systems. When we are in a state of shame or fear, our capacity to learn shrinks and there’s no room for new information because we are in survival mode. Key to learning and useful feedback is to find effective ways of engaging with people precisely when they are not managing to align with what they want to learn and integrate and support them to find an empowered path in response.

One of the ways that we have been attending to this challenge within NGL is by adopting the capacity lens as an antidote to shaming and judgment. It reflects a deep quality of trust in life and each other to recognize that each of us functions based on what is actually within capacity — always. The impact of being shamed or judged, so common within conventional educational settings, leaves us with less capacity, not more. Conversely, if we manage to genuinely trust and accept our own and each other’s capacity limits and do only what is within capacity, then overall capacity grows. This is one of our most beautiful and paradoxical discoveries: Staying within capacity increases capacity. For example, we engage in many “Experiments with Truth” within NGL. Initially, many of us were quite ambitious in the practices we took on or the duration of our experiments. Over time we learned that doing shorter experiments with a smaller range of practices was less likely to overwhelm us and to give us a sense of integration and learning at the end of an experiment.

From discipline to love as the foundation of teaching.

The love we are talking about here is the love of life, of liberation, and of each person who is coming to learn and engage with knowledge co-creation. Putting love at the center of teaching links education directly back to us being a mothering species. This includes and invites a deep level of trust in everyone’s inherent desire to learn, heal, and align with life. Trust, especially its deepest layer — trust in life, can antidote the deep reliance on control that’s been with us since the patriarchal turn. Such trust, supported by having a needs-based and capacity-based curriculum, effectively means that there is no need for any extrinsic motivation in the form of rewards and punishments. Learning can then be based on intrinsic motivation only, a true revolution in what education could mean which aligns it, again, with maternal gifting and with life.

Aligning global resource flow with maternal gifting

One of our deepest areas of experimentation is at the heart of the maternal gifting paradigm. It involves a radical shift from exchange-based resource distribution to a simple gifting principle that we have identified: resources flow from where they exist to where they are needed. Simple doesn’t mean easy, given the depth of patriarchal conditioning and the intensity of external mechanisms that reinforce scarcity and separation, which show up as accumulation and exchange. Within all this, it is a tall order to get to a state where the flows are accurate to what the needs, impacts, and resources are; where the commitment to keep reducing unwanted impacts is solidly co-held; and where everything is grounded within willingness and capacity in exactly the same way that it is in relation to learning.

Although we function on an extremely tiny scale relative to our global population, we see what we are doing as prototyping a global maternal gift economy. We are very conscious of our dire global situation and of the likelihood of human extinction, and simultaneously full of trust that what we are seeing is the result of profound multigenerational patriarchal trauma rather than inherent to human nature.

This orientation puts us on a search for an alternative to current systems. We carry a deep conviction that shifting from global capitalism to a global maternal gift economy is both entirely possible and likely to also shift us to a life-aligned course that would make near-term human extinction dramatically less likely. And while our actual experiments are in the area of social institutions (an economic system), thinking through how to scale them to the entire global human population is in the realm of telling a new story that invites us to truly imagine a shift from matching supply to demand in exchange to matching resources to needs in flow.

If we take seriously the possibility that what we see around us isn’t caused by human nature, then this becomes an engineering problem. Solving such problems starts with design principles that function as an initial response to the question: What are the systemic elements that would need to be in place for a global maternal gift economy to be possible?

Making information available and accessible. One key element of being able to flow resources accurately is that relevant information needs to be available and accessible everywhere. At the level of design, this entails three shifts:

From effective demands to needs. Effective demand is a tool which serves to move resources to where people can claim them through money, without any mechanism to make the actual need known. In our current systems, having a need lacks any power, because the power of needs only exists within an interdependent web of care and relationships where the spontaneous response to a need is generosity — precisely the mothering orientation that we lost to patriarchy. The shift to putting needs at the center, in other words, requires reopening ourselves to the trust with which we were born: that others will orient to us when our needs are made known.

From externalized costs to actual impacts. By and large, the theoretical premise within exchange economies is that all impacts reveal themselves through their monetary imprint. This directly leads to the practice of externalizing costs, which then means that the actual impacts are absorbed elsewhere. Market mechanisms were never designed to care for human needs and are therefore inherently inadequate to the task of putting information on the table, because they don’t include direct ways of measuring impacts. It’s a huge act of imagination to even ask the questions of what it would mean to actually measure impacts and internalize feedback loops: Would we then re-adopt the practice of making only things that last and that are necessary to address actual needs? Would we, both individually and collectively, change our practices once the information about the horrific impacts on people in many “supply chains” are made visible so that most of us would actually be able to take in what they are?

From accumulation and scarcity to making resources available. I believe it’s literally impossible to have accurate information about what resources actually exist within an economy based on money, exchange, and especially accumulation, because this economy inherently creates scarcity. We would never throw away edible food or useful items except to keep prices down and keep sales going. Instead, what I can see possible is a dynamic, interactive system, based on technologies that already exist, for deciding who grows what where, and what will be produced where, so that we can can ultimately sustain the entire global population within the means of the planet.

Choice within togetherness

One of the many reasons so many of us are stuck within neoliberalism and see no other option is that we have been driven to believe that the only alternative is top-down, centralized planning in which our lives would be controlled by others who, like most parents, presume to know what our needs and capacities are. I could say a lot about how we got to where this either/or is almost all we know, which is not within the scope of this already very long article. What is more significant for this moment is to note that alternatives do exist. In Rojava, in Catalonia during the Spanish Civil War. In Chiapas, and in scores of undocumented spontaneous self-organized approaches, especially in response to situations in which central control falls apart. Such examples show that solidarity arises when needs are exposed, when trust in the capacity of the powers that be to address the needs is broken, and when some people take initiative and make things happen.

From what I have read and heard, such experiments involve no centralized planning or authority telling anyone what to do; people choose for themselves. At the same time everyone is oriented to the whole, not just to their own well-being; a sense of “We’re all in this together” permeates such experiments and brings people together. As I see it, at any scale, sufficient choice, sufficient togetherness, and sufficient leaning into trust in life are a path to restoring flow. The rest is an engineering problem, and we know how to address those.

Self-definition of needs. I consider the desire to quantify and to be able to make objective measurements of everything, including needs, as part of the problem, not part of the solution. I don’t believe any pathway to a livable future can proceed through telling people what they need because they fit this or that category; are this or that height, weight, or skin color; or have this or that many children. At the same time, restoring our capacity to assess what we actually need when we are habituated to scarcity and separation is no small task.

Still, recovering this capacity, collectively, seems to me essential for a livable future. It starts from realizing no one from the outside can tell anyone else they don’t have a need they experience themselves as having. If there is going to be a shift in how we relate to life, I see it coming from holding all the needs in some complex kind of togetherness, until the layers of protection soften and we can all hold everyone else’s needs alongside our own. That is what allows choice to happen within togetherness.

Staying within capacity and willingness.

One of the main casualties arising from living in exchange-based relationships is our access to generosity, which erodes rapidly whenever we do anything for extrinsic reasons. And yet the idea that anything will get done without incentives is extremely difficult for most people to accept as possible. What of all the work of administration, maintenance, and manual labor? Who would do all this if there wasn’t an incentive? My belief, partially based on experience, is that our evolutionary, collaborative, and generous makeup will reawaken when we what we do is all and only what cares for needs — without excess for profit, without massive work to protect access for the few, and without so much that we consume to compensate for the impact of living in so much scarcity, separation, and powerlessness.

Distributed, collaborative decision making.

This aspect of what it would take to create a global maternal gift economy may be the most difficult to imagine because it challenges two deep premises of exchange-based economies, and especially the capitalist version of them. One is that we are fundamentally self-interested and don’t really care about others or the whole. The other is that if we release all attempts to coordinate or bring active care at any level other than individual actors, then the totality of our activities, via the putative “invisible hand,” will bring about the best social benefit without ever intending it.

Instead, and in line with everything I have already laid out here, my belief is that it is entirely possible to coordinate and make decisions through mutual influencing and without anyone telling anyone else what to do. Just like communism, everyone’s needs and capacity are in the picture, with an intention to care for all the needs within overall collective capacity. Unlike capitalism, no one is free to accumulate at the expense of others. Unlike communism, there is full trust in life that people, on their own, without anyone deciding for them, can engage with each other and reach decisions that optimally flow resources from where they are to where they are needed, based on full willingness and capacity, and with the least unwanted impacts.

Nothing resembling this has ever been tried on any significant scale, let alone with a population of over eight billion people globally. It takes enormous courage to even name it as a possibility given the current state of affairs, and still I do. If ever enough of us came together to experiment on a large scale, we would no doubt encounter many challenges and many miracles and learn an enormous amount of principles and practices that would support us in the implementation of such a massive project. What comes next is, by necessity, a minuscule preliminary set of guidelines that I consider indispensable for such an experiment to be possible.

Matching resources to needs as locally as possible.

The current globalized market knows no borders and has no limits on how far and how exploitative it will get. The quest for new products, new markets, and ever lower production costs is a key driver in environmental degradation and in the instrumentalization of all relationships. Within a full global gift economy we restore relationships and our planet by having the bulk of the matching of resources to needs happen locally. Beyond the local, we would need mechanisms for making the information about needs, impacts, and resources transparently available to neighboring regions and beyond. Establishing gift links between regions around the world can facilitate the flow of information from place to place, make the needs real, the impacts visible, and the available resources known. (I have written a synopsis for a feature film called Wisdom Tales from the Future about a future organized along the outline of this part of the article, which includes a fictional transition story with many more details about what this could plausibly look like.)

When that can happen, the giving is informed by clarity about how to care for the whole, absent the attempt to extract, accumulate, gain advantage, or simply be comfortable and save money without acknowledging and sometimes even knowing it’s on the backs of others and all life.

Attending to essential needs before anyone gets more.

At present, within the scarcity that is generated within market economies regardless of how much is actually available to us, the primary way that we relate to each other in the context of finitude is competition bounded by rules and norms such as “first come, first served” or “equal sharing,” neither of which has any relationship with actual need.

Changing this ongoingly grooved habit begins from the deep trust in our human capacity to spontaneously orient towards giving when we fully understand a need that is present, and simultaneously trust that our own needs are cared for by others. And even as someone with full access to such trust I am aware of the tragedy that under conditions of scarcity, separation, and powerlessness, we become constricted and our imagination withers away. This means, to me, that any transition would need to unfold one baby design step at a time.

For example, flows between localities would need to be designed in ways that demand less intensive attention and rely on general patterning rather than individual variation, while keeping aside resources for unexpected needs. A key element of this kind of orientation is to remove money from the equation — which I believe is an indispensable move. This then makes it possible to look at the actual material resources that are needed and to flow those. When we achieve that we may finally have collectively discerned access to the entire material infrastructure and all the life energy needed to sustain all that is required for all of us to live well within the means of the planet. When the resources being distributed are material (and not abstract like money), I fully trust the power of others’ needs to influence our choices and the capacity of our big brains to solve complex problems collaboratively.

Collaborating in the face of finitude.

The biggest test of all for any approach that leans on our collaborative capacities is when the reported need exceeds known resources. All existing mechanisms I am aware of in our current systems are ultimately coercive and outside relationships. The deepest question of all is whether we can create mechanisms that are robust enough to support a creative outcome without reverting to the indifference of markets, to imposed regulation, to norms and rules that don’t attend to actual needs, or to outright war.

I don’t pretend to have a full answer. And I do have one inspiring example: the acequias, a system for collaborative stewarding of very limited amounts of water in the southwestern United States of America and elsewhere. The system was brought to the state of New Mexico in part through colonization and has functioned, uninterrupted, for a few hundred years. It involves collaborative and distributed management of water access through somewhere between 700 and 800 gravity-fed ditches that average about 6 km (3.7 miles) in length. The system as a whole, in other words, is about 4,500 km long! Everyone knows when they can water their gardens and crops and when not. Some people take on specific functions such as switching valves and caring for other elements in the system. There are mechanisms for dispute resolution and much else. And this is water, the quintessential scarce resource over which, we are told, wars are fought. Instead, this system, which is both distributed and collaborative as commons generally tend to be, has been a robust support for local people whose economic existence is precarious, as well as for the local vegetation which, within this system, is more abundant than in areas of the desert where people are not using the water.

This, to me, is the future we can have.