By Miki Kashtan

Part 1: Linking Education to Larger Systems

What might human life be like with a radical reimagining and implementation of the ancient life principles of flow, togetherness, and choice? What is ours to do in the face of the immense gap between this vision and what we see around us? Ecoversities allies around the world are grappling with such questions as they work to envision and practice educational and community ways of being that support care for all within the means of the planet. Nonviolent Communication (NVC) practitioner, author, and facilitator Miki Kashtan shares her vision, now a living experiment in process within the Nonviolent Global Liberation (NGL) Community she birthed, in this three-part series we are pleased to debut.

In the weeks leading up to writing this piece I had the disturbing and illuminating experience of watching the documentary Schooling the World. This film helped me see more vividly than before the direct link between schools and global systems of capitalism that focus on extraction and exploitation. The principle that I rely on in this article is that educational systems are more generally linked to the larger social institutions as well as to the mindset that a given society includes and is based on.

The overwhelming majority of our species currently live within a patriarchal paradigm that is at odds with life and our evolutionary makeup. Its current manifestation is global neoliberal capitalism. It is reproduced, in part, through educational processes that prepare each of us to function within it. Despite how deeply embedded these systems and their interrelationships are, I hold the conviction that it is possible for humans to realign with life principles within a paradigm based on what I am referring to as maternal gifting.

As in any other social system, this approach spells a link between how learning is organized and how larger systems are organized. This applies to both the possible future society and the journey some of us are already taking and inviting the rest of us to join. At present, given the sheer magnitude of the gap, this journey is by necessity experimental.

The term “maternal gifting” was likely coined by feminist philosopher and economist Genevieve Vaughan. She drew the connection between maternal giving and the gift economy, a connection that is mostly lacking in other discussions of gift economy. I look at the maternal gifting paradigm as integrating three principles or insights that help to make sense of who we are as human beings: the biology of love, maternal giving, and the orientation of reverence for life.

The biology of love

The framework of the biology of love originated with biologist Humberto Maturana Romesin. I believe that one of the reasons this term is very little known is that he was from Chile, and that fits within patterns of knowledge production and consumption that are embedded within global capitalist relationships: Little attention flows to those from the global South.

I also believe that he is not very well known because his thinking challenges everything that we are told about what humans are within mainstream, patriarchal approaches. I see Maturana as a pioneer in reshaping our understanding of how evolution works, proposing what I see as a feminist path that is profoundly relational while remaining consistent with genetic theory.

He collaborated with psychologist Gerda Verden-Zöller in writing The Origins of Humanness in the Biology of Love, where they argue “that human beings belong to an evolutionary history in which daily life was based on cooperation and not domination and submission … [and] the basic emotion or mood was love and not competition and aggression.” Humans, according to them, evolved separately from chimpanzees, forming a different lineage that conserves the loving nature of mother-child relationship into adulthood, while for many mammals the prevalent mood of adulthood is one of dominance-submission relationships.

One of the significant consequences of being in this lineage is that we remain dependent on love for our entire life. Given how much patriarchal systems function in separation, this insight in itself can sufficiently explain the degree of suffering that is so common within human societies in the last several thousand years.

Maternal giving

The framing of maternal giving as the foundation of the gift economy is based on the simple and highly disregarded insight that all of us are alive because someone gave to us knowing full well that we couldn’t give anything back. As Genevieve Vaughan reminds us, infants cannot survive without the gift of mothering. She refers to us as a “mothering species” because of how central this orientation is to our very survival. She sees mothering as going beyond giving birth and even ultimately independent of it: it is an orientation to the needs of others and a fundamental willingness to give to others unilaterally and unconditionally. Nothing is expected in return and there are no preconditions. This form of giving also means, on the other side, that all humans are born into unilateral receiving. Within societies that put mothering at the center as a core organizing principle of how they function, we all orient in this way. This in turn leads to all of us thriving.

With or without linking to the maternal giving insights, an expanding body of scholars ranging from archeologists to economists believe that pre-patriarchal societies were radically different from what we now know. While no unified term for such societies exists — some call them matriarchal and some use other terms such as matricentric or matristic— there is a growing agreement that such societies are deeply egalitarian and function without structural differences in access to resources. Power is based on entrustment of those with natural authority, often “the person who cares the most for everyone,” as German philosopher-researcher Heide Göttner-Abendroth explains in her 2012 study Matriarchal Societies, rather than on fear of consequences based on external resources. Everyone’s needs are included when allocating resources.

Intricate and ongoing cooperation happen, as Maturana and Verden-Zöller describe it, “in the domain of mutual acceptance in a co-participation that is invited, not demanded. … Its realization occurs in play … in the enjoyment of actually doing things together.” The early and indispensable unilateral-giving orientation towards the young continues into adulthood and forms the basis of all social arrangements.

Reverence for life

The biology of love is also a biology of trust in life. Reverence for life is an organic and integral aspect of this trust. I believe that, prior to patriarchy, reverence for life meant an active relationship with the entire web of life. When we orient from within such reverence we learn to take only what we need, not more and not less. This practice is an expression of full trust that when we honor our relationships with our plant and animal kin, when we accept mystery, when we live in full humility and honor the limits of our knowing, and when we overall surrender to life, there will be enough for all needs over time within the magical flow of life. This experience is almost entirely foreign to modern humans, although it still exists in at least some Indigenous societies.

Putting it all together

Neither Maturana nor Vaughan saw the link between their bodies of work. I may well be the first person who saw that link, and we have been leaning on it heavily within the Nonviolent Global Liberation (NGL) community that was born through me. As I see it, this is a link between the social and the biological.

When Vaughan says that we are a mothering species, she is asserting that our evolution is inextricably linked to mothering. The significance of it is that when we replace the mothering principle with mechanisms of control, we interfere with our very evolution. This is because unilateral receiving is needed to reach adulthood, which makes maternal giving a biological necessity. All babies require it, and this is what shapes all of us.

It creates what Maturana refers to as our “manner of living,” which is the link with the social. When we put mothering at the center of how we organize our living, it influences everyone and creates a manner of living in which everyone mothers. Mothering, in this context, is simply an orientation towards others’ needs, a continual and collective flow of gifting linked to trust in life. Within this flow, all of us are cared for by all of us.

The result is peaceful, loving, collaborative societies thriving in balanced relationships with each other and the wider web of life, where women, men, and children live in relaxed trust of self and other. This is what settlers encountered in North America, which they wrote about in their diaries and then proceeded to destroy and tame. This is why the Haudenosaunee form of self-governance, for example, which is based on nonviolent and cooperative principles, has been in continuous operation for a thousand years, even within extreme conditions imposed by colonial settlers in today’s United States of America. This is also why in what is now the western USA, Europeans found thriving economies they could not understand. Nothing in their experience prepared them for truly regenerative abundance that is based on a collaborative relationship with the land and doesn’t depend on tilling and other extractive practices.

The patriarchal paradigm: scarcity, separation, and powerlessness

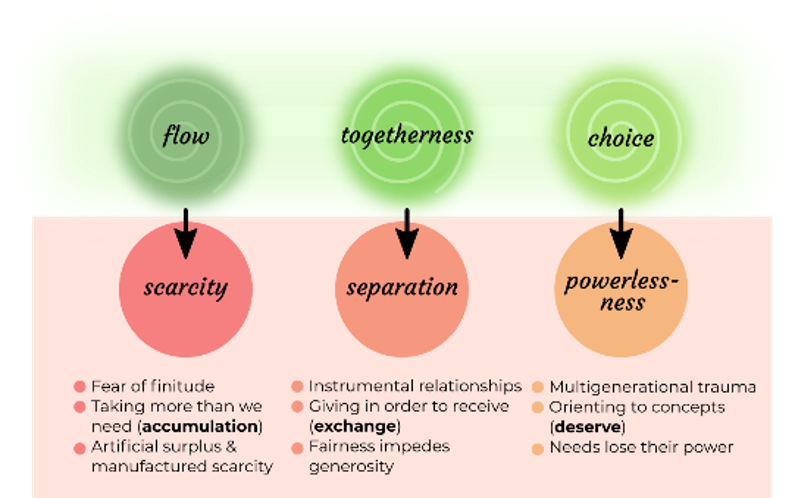

What happened that got us to lose all of this? How is it possible that egalitarian, peaceful, and stable societies which functioned in flow, togetherness, and choice turned into patriarchal societies based on scarcity, separation, and powerlessness?

To even ask the question is to be able to fully imagine that past as a real possibility, which the majority of scholars don’t. Even though the notion of an original matrilineality preceding patrilineal arrangements was quite common among archeologists and others in the 19th century, it was eventually abandoned because of what it challenged: According to Nicholas J. Allen et al., in Early Human Kinship: From Sex to Social Reproduction, this notion was rejected for political reasons because it had been adopted by Marx and Engels.

Modern human sensibilities are based on the assumption that some version of domination is inherent to human nature or necessary for social order, especially once we shifted from foraging to cultivating food. This understanding has been normalized to the point of not being questioned. The onus is on those of us who believe otherwise to make a compelling case for patriarchy having been caused by events on the material plane.

This is precisely the task taken on by independent scholar Heide Goettner-Abendroth (Matriarchal Societies of the Past and the Rise of Patriarchy: West Asia and Europe), and others, such as the collection edited by Cristina Biaggi, The Rule of Mars: Readings on the Origins, History and Impact of Patriarchy. Their work leans on and follows earlier work by Marija Gimbutas, such as in her book The Civilization of the Goddess. Their conclusions, many of which are now supported by DNA bone research, are that patriarchy emerged from local, specific conditions external to the spontaneous unfolding of any culture. These were major calamities, either of a natural order (e.g. desertification, flooding, or populations exceeding local resources) or from invasions, which interfered with trust on a scale large enough to overwhelm collective capacity to the point of trauma on a group level, with no prospect of metabolizing the impacts or of recovery.

This is the inception point of scarcity, which is a relationship with finitude that is based on trauma, from which patriarchy emerged as a fundamental orientation to being and living that is at odds with life’s flow. And we have been in collective trauma ever since, passing it on systemically and intergenerationally.

“One of the deepest tragedies of patriarchal economic systems is that when the gift of mothering becomes exploited within the exchange economy, it shifts from being freely given in generosity to being expected as a form of sacrifice.”

Once trust in life is lost, we are far less likely to gift anything, because it then feels like we will end up with less. Patriarchal economic systems are all set up on extraction, exchange, and exploitation, all of which are geared towards accumulation. One of the deepest tragedies of this is that when the gift of mothering becomes exploited within the exchange economy, it shifts from being freely given in generosity to being expected as a form of sacrifice. Each culture has its own version of how women are then expected to be the caregivers regardless of any capacity limits and often with little support.

All this, writ large, is why patriarchal societies are never stable. They require an ever-expanding economy backed up by state violence to make possible progressively more accumulation of what no human actually needs through more extraction from the many. All social orders that emerged since patriarchy lean on coercion and shaming in their explicit and implicit political, economic, and cultural arrangements and in relation to new humans.

Patriarchy shifted us — all of us, not only women, not only children, not only some groups —from flow to scarcity, from togetherness to separation, and from choice to powerlessness. The gap between these two ways of being is a tragedy beyond words. What we have lost is staggering.

We lost contact with our evolutionary lineage of love and reverted to an earlier phase of dominance and submission. We lost our trust in life and have lived, ever since, in an endless and futile attempt to control life. We lost our communal existence, especially with the rise of capitalism, and now exist as individuals who need to fend for themselves. And we lost the power that needs once held to invite the flow of gifting and our own power to know how to care for our needs within the interdependent web of life. Now, outside infancy, we can only care for needs if we have something to give in exchange for what we receive.

It is beyond the scope of this article to detail all these losses. As a result, I am focusing here only on one that is less commonly understood and that is significant for any possibility of restoring our capacity to align with life: loss of reverence for life.

With the patriarchal turn, we eventually came to separate mind or spirit from matter (with its non-accidental etymological root of mother!) and to devalue the material more and more over time. For some millennia, until the 18th century so-called enlightenment, some form of reverence was still preserved as faith. I consider this already a loss of the original and organic trust in life because faith is removed from the material plane by being directed towards a transcendental force. And it is still something that preserves our relationship to mystery.

And then we lost this layer, too, a loss captured by sociologist Max Weber with the phrase “the disenchantment of the world.” We no longer have even faith. On the global scale, the intensified disdain for what is now thought of as inert matter has made it possible to dramatically accelerate the processes of extraction and plunder. On the individual scale, it has led to a chronic experience of profound disorientation and loss of meaning. I believe the latter is so pronounced because some form of tapping into mystery, faith, or similar deeply felt states of being is an actual human need that is an aspect of the overarching basic human need for meaning.

And this is only one example of what the patriarchal turn has done to us. The mourning in me is immense, and I consider it vital to the work to pause and be with the mourning — me while writing, and anyone else while reading — in order to keep our hearts soft, loving, and ready for the work that awaits us to bridge the gaps.

How social orders reproduce themselves

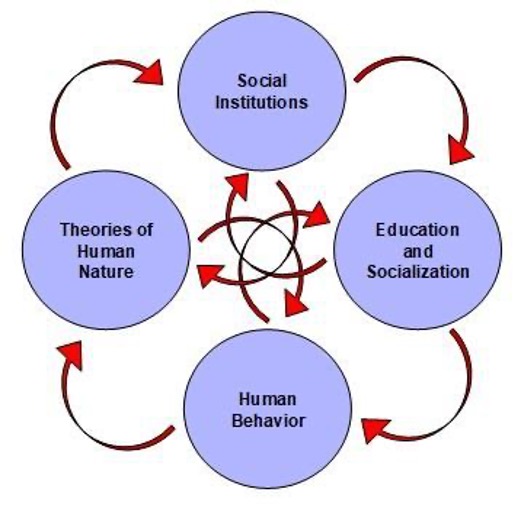

All social orders reproduce themselves through a complex interaction between four spheres of human existence that are schematically captured in the diagram above.

All societies have social institutions, which are the larger systems of how the particular society as a whole functions. All societies have their form of education and socialization which is how the culture moves from generation to generation. All societies have their unique ways of functioning in terms of how humans interact with each other and the larger web of life. And all societies have stories such as those about what it means to be human, what a good life looks like, or how we came to be.

And all these elements, these schematic four spheres, are interrelated in multiple ways. We function the way we do mostly because of what we learned in our early years, and that learning is reinforced by the stories we absorb from others and from the larger whole. We socialize the younger people based on knowing what institutions they will live in as adults and wanting to prepare them for that life. And we build our institutions based on what we see around us in terms of how humans function. Those stories also justify the systems that exist and the way we socialize our young.

There is no simple linear relationship. The diagram attempts to capture that by having arrows going in all directions. These cycles function in all societies, both those within which humans thrive and those in which humans suffer. And they look dramatically different based on the mindset that drives them. The table below lists how maternal gifting societies and how capitalist patriarchal societies reproduce themselves and what the four spheres look like in each.

After about 5,000 years of patriarchy, we are now a very low-capacity species. In particular, we function in massive disempowerment and are unable to make decisions together nor to care for each other and the wider web of life. Our ability to discern actual needs and direct resources to where they are needed is almost non-existent.

If we want to realign ourselves with life again, all four spheres will be relevant, as we will need to build enough capacity and resilience to turn the tide on all levels and in a way that can sustain itself intergenerationally. Below, I provide a high-level conceptual map which is not an exhaustive “recipe.” The specifics, at each of the levels, are endless and go well beyond the scope of this article.

Social systems

Creating change in our larger institutions, if it can happen at all, will likely include collective action to change how decisions are made and how resources are used and distributed.

Such collective action will likely include both nonviolent resistance and what Gandhi called “constructive program” and what Joanna Macy refers to as creating alternatives. The focus on decision making is different from most collective action efforts that usually orient to changing specific decisions rather than the foundational rules of how patriarchal systems function. Within this, building the alternatives often means creating blueprints that then make it easier for others to find them and use them in more settings until, so the longing goes, they might become common.

Education and socialization

At its best, what education can offer is supporting the next generation, with humility, to reduce the gap between what we have now and the vision of what’s possible for humans in terms of realigning with life. This is education for deep liberation. Given the significance of this task, I include below an entire section on what it can look like to fully rethink how we orient to learning, teaching, and the sacred task of supporting younger generations.

Human behavior

Our task in this area is to support all of us who are open to it in relearning to function in line with life, which means consciously choosing to exit the deep patriarchal grooves of our socialization. Our first step, usually, is to restore choice. This is because we need enough access to choice to be able to restore togetherness. Without it, we are too likely to imagine ourselves in togetherness while maintaining within us an either/or mindset. We either lose ourselves or maintain some separation, especially when anyone does something we don’t like. Ultimately, we need to relearn to have choice within togetherness rather than instead of togetherness. And this requires much more inner strength. Similarly, we are unlikely to restore flow without restoring togetherness first, because human flows depend on trust.

“The Story”

Stories matter. Because of this, if we want to turn around the march to extinction, our task is to tell different stories. One purpose of new stories is to counter the pervasive myth that” there is no alternative” to the current systems (also known as “TINA” and originally coined by Thatcher and Reagan). Telling a story of possibility brings forth a vision that can then remind people of who we are and what may still be possible. Because of this, I included a whole section called “Wisdom Tales from the Future” in my book Reweaving Our Human Fabric. The bulk of it is twelve fictional stories about what life could look like in a post-patriarchal world. My purpose was specifically to show, in minute detail, life outside the familiar, and in that way to fertilize my own and others’ imagination.

The other purpose of telling new stories is to make the gap visible. In order to be able to mobilize ourselves to move in the direction of vision we need to be more aware of the costs of what is happening, which are currently hidden from sight through supply chains and outsourcing of violence. Knowing the gap is part of rekindling life within us so we can mourn and choose to take action.

I believe that every article that’s ever been written is a story which either reinforces the status quo of the patriarchal social order or points us in the direction of realigning with life, what some Indigenous people invoke with the phrase “ancestral future.”

This article is no exception. In this first part, I’ve focused on telling the story of the maternal gifting way of living, how we left it, and what we might still do to realign with it, and situating education within this story as irreducibly linked to the entire social order. Education, in general, is an elemental aspect of any society and usually reproduces the ways of functioning and thinking within that society.

In the second part of this article (linked to here), I tell a story of possibility, also focused on the link between education and the larger social order. One part of this new story is about how education can be reshaped to become a tool for transforming the social order through applying principles that call into question norms, assumptions, and practices that reinforce the current capitalist patriarchal social order (as those in the Ecoversities Alliance are striving to do). The second part of this new story is about what it would take to reshape resources flows, on a global scale, to where the organizing principle is about moving resources to meet needs rather than to where resources already exist. Both of these spell radical departures from business as usual.

In the third part of this article, I share two actual case studies from applying these principles in a particular context — the Nonviolent Global Liberation community. It’s a different version of telling a story of possibility, focusing more on the nuts and bolts of actually trying to live differently on the material plane, building an alternative on a small scale, discovering the depth of internalization of the very thing we are trying to transform, and taking a journey made up of many baby steps. Once again, the focus is both on education and on the larger systems. We see the first experiment as seeding a “Liberation University,” and we see the second as prototyping a global maternal gift economy.

We are quite far from complete proof of concept, and we are tiny on a global scale. Still, at the scale we are operating on, and given the immensity of internal limitations and external obstacles, I believe these case studies show that no matter how far from vision and how low capacity the human species currently is, openings exist for us to play big, take ourselves seriously, and move ideas into action.

Miki Kashtan is a practical visionary exploring the application of the principles and tools of Nonviolent Communication (NVC) to social tranformation. She dreams of local and global systems based on care for the needs of all life. She is the mother of the Nonviolent Global LIberation (NGL) community, and all she does emerges from and ffeeds that experimentation. She has written four books and has published articles on many platforms. She blogs on The Fearless Heart.

We invite you to read the second (more specifically focused on transforming educational models and resource flow systems) and third (sharing case studies) parts of this article as well.