A month prior to the Global gathering of 2019 in Michoacan, Mexico we had come together at the source of the Nile near Jinja in Uganda for a First African Ecoversities gathering. We extended personal invitations and reached out through our networks to share about the community of learning practitioners from around the world that is cultivating human and ecological flourishing in response to the critical challenges of our times. We received twenty-five registrations of people involved with alternatives to higher education reclaiming knowledge systems and cultural imaginaries in an effort to restore and re-envision learning processes. The gathering brought together educators, scholar-activists, independent researchers and curators, filmmakers, rappers, muralists, philosophers, organizers, choreographers and chief listeners.

Choosing Jinja meant meeting each other with the source of the Nile as our echo. A great source of inspiration lied in our coming together from North, West, East and Southern Africa to spend five days together in the Pearl of Africa. The objectives that informed our tentative flow for the five days spent together included: learning about each other’s contexts and how our work reflects these; listening to land, people and each other; discussing pedagogical practices and formats; conducting a field trip; and reflecting on our pedagogical tactics and strategies in light of socio-political constraints and repression in dealing with authoritarian regimes, military rule, censorship, restrictive NGO laws, etc.

Our first regional gathering in Africa welcomed twenty people from nine countries. It was a rare opportunity for people from across the continent who were looking to exchange on alternatives to mainstream education to do so on the continent. Listening to each other’s stories, anecdotes and trajectories in relationship to emergent spaces, initiatives and networks in South Africa, Egypt, Morocco, Uganda, Nigeria, Senegal, Congo and Kenya was both eye-opening and heartwarming.

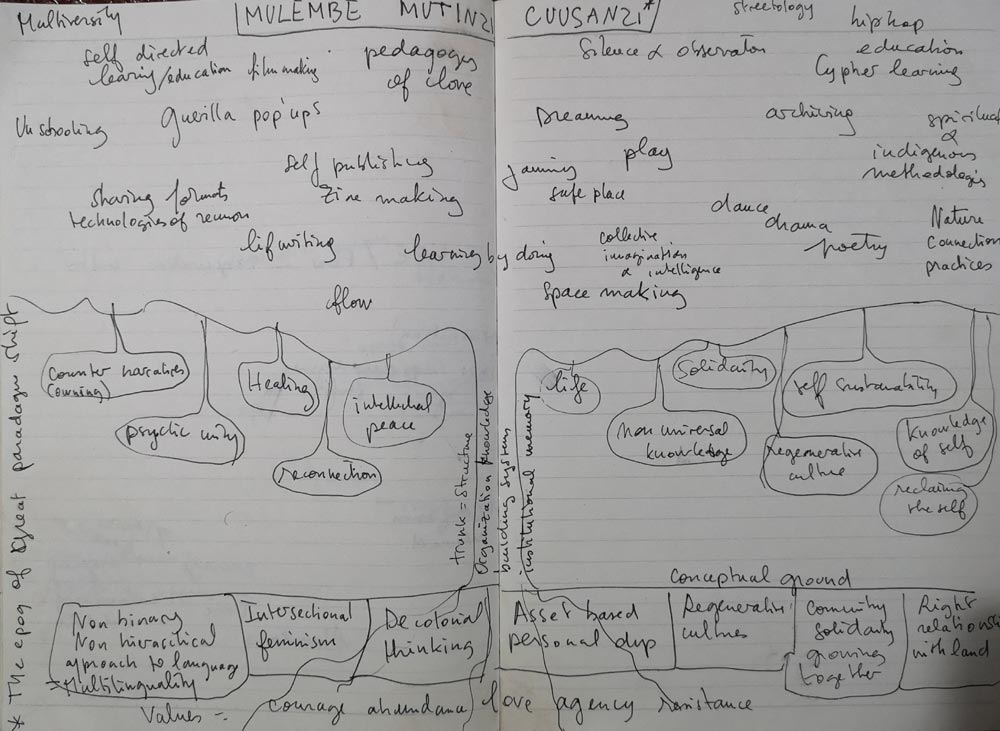

Our conversations revolved around non-binary and non-hierarchical approaches to language and multilinguality; our relationships with land and bodies of water; intersectional feminism; our work in and with communities; decolonial thinking and regenerative practices; archiving and self-publishing; film and space making; unschooling and hip hop education, among other things. Two themes resonated at the gathering. The first theme is that of Mulembe Mutinzi Cuusa-Nse – or the Great Turning in Luganda – which refers to a prophecy that was received by African spiritual leaders fifty years ago and that emerged in the face of a world depleting to perilously low levels of its material basis for its continued existence.

The prophecy calls our attention to “the declining humility to recognize and celebrate the right to the self-determination of all the peoples, nations and countries of the world” (Wangoola, 2019). Mulembe Mutinzi Cuusa-Nse signals an opening for the revitalization of Indigenous knowledges and the re-emergence of the spiritual philosophy of Tondism which derives its name from the East African God of Peace Katonda and reminds us of the land where all human life began and with it all human spiritual and intellectual life.

A notion that intrigued us at the first African gathering was brought up by Capetonian street artist, muralist and illustrator Breeze Yoko (see his sketch on the beginning). Breeze recalled his formative years in South Africa finding ways, loopholes and opportunities to a particular awareness he had developed in the streets of the township he grew up in. He came to call this awareness, broken down into presence, observation and action (in that order) – Streetology. Breeze’s storytelling on his urban experiences resonated with folks who had grown up or spent time in Lagos, Casablanca, Dakar, Kinshasa, Nairobi, Cairo, Kampala and Johannesburg. Breeze’s Streetology was invigorating – not debilitating – the experiences lived in African cities. It was celebrating movements and motions, fashion statements, choreographies, sounds, subversions, make-shifting and shape-shifting. Breeze was reminding us to look at daily struggle, hectic hustling and precarious lives with fresh eyes that would allow us to see the street smartness, or the idea of ‘seeing what might happen’ as a quintessential tactic (Simone, 2005) performed by African city=dwellers. Breeze was drawing our attention away from the predominant framing of African cities as wounded places, whether wounded by war, famine, disease, poverty or political turmoil.

It’s worthwhile to remember that Africa’s cities have been connected by networks of trade and knowledge exchange for centuries. In the 21st century some of these ancient meeting places have grown into the fastest growing cities in the world. By the end of this century Dar es Salaam, Kinshasa, Cairo, Johannesburg and Lagos are expected to grow into mega-cities with well over 50 million inhabitants. Hand in hand with such demographic growth and urban concentration arise pressing urban challenges related to motorized and non-motorized mobility, human and food security, mental and physical health, and affordable and precarious housing to name a few. This transformation of African cities is changing the way they are being experienced by their inhabitants; from the sweet smells of the shisha cafes in the streets of downtown Cairo to the smell of toxic damps of the Agbogbloshie – the large e-waste sites in Ghana; from the sound of a Kora played by a Malinese storyteller to the ticking of the keyboards in the hackerspaces of Kenya’s Silicon Savannah, and the electronic beats of nightlife in Lagos. For us as learning practitioners, educators, scholars, artists and activists, Streetology invites us to pay attention to urban ecologies, local histories and geographies, the social production of spaces and the making of places, processes of dispossession and displacement both in inner cities and in peri-urban areas, the securitization of gated communities and the militarization of shantytowns, car sharing apps and informal transport systems, street food cultures and gang cultures, urban land- and soundscapes..

How do we bring Ecoversities into conversation with cities, their echoes and their streets. Late capitalism often manifests most visibly in urban settings as they provide investors with the prestige and glamour of adding to the built environment. That these additions are often made at the cost of forced removal, demolition, uprooting and displacement, tend to remain unnoticed. Structural violence, modern/colonial or otherwise, plays out spatially and at the expense of bodies of color who are at home in cities of the global south. As a trans-national alliance, it is paramount that we tune into Streetology.

Download the First African Ecoversities gathering report