Written by: Andrea González and Juan José Lugo

Revised and edited by: Maru Vasco, Sierra Allen, and Alessandra Pomarico

Abstract

Along the paths of our lives, we will find many approaches to what seems appropriate, what seems to be what we want, what we can do, how we make a decision, and how we relate with others and our environment. The ways we learn and unlearn are all related to how we decide to manage this process. This article talks about a way of learning from the world, a form of pedagogy, and an axis in our paths. This is about the importance of caregiving, a subject that has emerged while working and playing with the profound spirit of regeneration and the healing practices that are born along the way. It also shows how a private initiative (Pangea), driven by regenerative principles, can get involved with a public institution and facilitate communal development in a highly dense urban area in the middle of a city.

The Andean territory is where we practiced and learned what this article has to share. Here, caregiving practices are essential foundations of community life. If another person is well and cared for, the community thrives – not only the human community but also the natural environment that surrounds it.

Through these lines, we want to share the experience of a pilot project that took place at La Huerta que Cura (The Healing Garden), a community garden in the Elders Hospital for Comprehensive Care, in the city of Quito – Ecuador. A green space co-designed by the elders and the volunteers, following principles of permaculture, where a lot of dedication, discipline, care, and commitment were put into place.

How did the healing garden emerge?

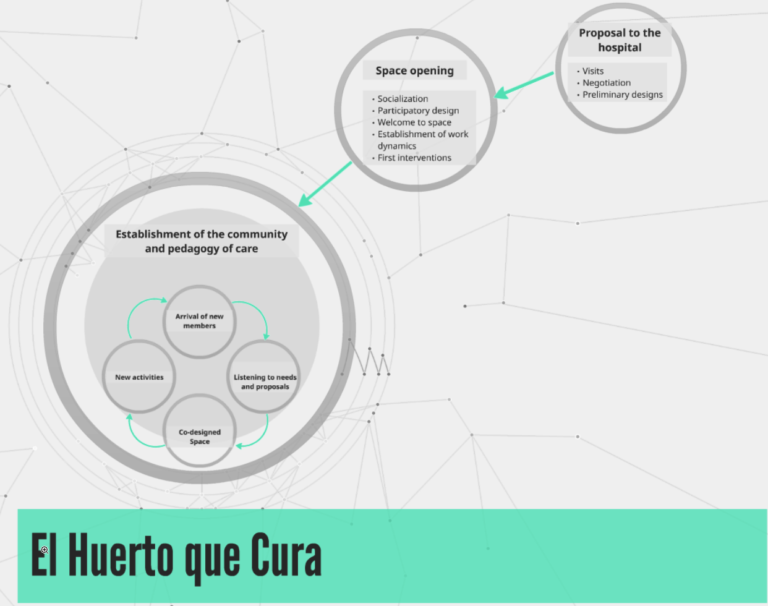

An underused green space was found within a public hospital in May 2019; the project was designed after getting to know the staff and a group of volunteers who were hosting workshops with the elders. This initiative entailed the creation of a therapeutic garden co-designed and developed by the elders (who were about to be dismissed); our proposal was accepted and implemented. This process was planned to follow permaculture’s guiding principles and ethics.

The project recognized that our relationship and connection with land has been, for thousands of years, the way in which people define their own spaces; and what has allowed diverse communities to flourish (Prest, 1988, Gunnarsson, 1992, Gerlach-Spriggs et al., 2004, Söderback et al., 2004, Greenleaf, 2014, Menatti & Casado da Rocha, 2016, Ulrich et al., 1991, Huisman et al., 2012). The development of the project has sought to revive this relationship with land and allow those factors that renew and heal to manifest and express, in order to create bonds between the self and the landscape.

To date, more than 40 grandparents have passed through the garden, of which 9 have decided to be part of the community garden by voluntarily attending the sessions held. Time and experiences during the development of the project made evident the elements that provide the garden community with learning lessons, tasks, and clues around spaces for healing, caregiving, and community life. This knowledge should be analyzed and shared to promote the dissemination of regenerative impulses within cities.

Elders Resuming their Place in Society

The proposed project was executed within the individualizing modernity of Quito, the capital of Ecuador, managing to introduce concepts such as the appropriation of public space, the redefinition, and empowerment of health, the recovery of underused green spaces, and community care, all within a public hospital dedicated to elderly people.

The construction of the spaces is framed by various elements, each place with its own layers of complexity. For the purposes of this article, it is worth situating the elders and their position in society within their territory. Part of the motivation for this initiative arises from a social notion within the Ecuadorian and Latin American context of the city / urban / modernity that at a certain age people are no longer useful to society. We have forgotten how to respect the elders as wise, keepers of vision, and storytellers. They have been relegated to “retired” and have stopped being productive for the system. However, their bodies embody the life of our society, telling stories that transcend time and space, allowing us to see their struggles and experiences of inequality, social injustices due to race, class, colonialism, origin, or sexual orientation.

In Ecuador and Latin America, the population of elders has grown, according to data from ECLAC (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean) and the UN (United Nations). Life expectancy at birth in 1950 was 52 years, for 2015 to 2020 life expectancy reached 72 years and the estimate from 2070 to 2075 is 85 years (González Ollino, 2018). There is a change in the social age structure which entails a transformation in the configurations of the social and economic contexts that must be taken into consideration to analyze the present and future of Latin American and Caribbean societies.

In relation to the statistics presented above, not only is there a need for prioritizing attention to this growing population but also the human and social aspect calls us to generate different initiatives, policies, and spaces that can assure tending to the elders and their needs, providing the forms of care and attention that they deserve.

A process of evolution towards regeneration through learning and caregiving.

As mentioned at the beginning, this essay seeks to tell the story of this caregiving laboratory as a pedagogical practice for regeneration.

Linking self-managed initiatives with state public spaces is quite new in the practice of government entities. Strict codes, bureaucracy and even political interests can be strong elements defining and interfering within these spaces. However, community awakening is a potential path and exercise for citizen’s empowerment.

There were different project stages that we went through.

Elderly Hospital for Comprehensive Care

Receptiveness started the moment the hospital’s head of maintenance (German Navarrete) got to know the social dynamic that was taking place inside the facilities: grandparents who were going to be treated for their illnesses and also got the opportunity to meet other grandparents and enjoyed a shared moment outside of their daily routines.

The hospital door was then open for Juan José Lugo (a member of Pangea, a private initiative that proposes regenerative design of spaces), to visit and approach the patients. After several visits, he was able to identify those in the chronic section who wanted to participate in activities that complemented their well-being and contributed to their health´s empowerment.

The idea of sustaining a therapeutic community garden in the hospital’s green space was then contemplated. The first conceptualization of the project was elaborated and later socialized with the director and the maintenance manager. After several observations on the proposal, a legal agreement on the use of the space was signed for a period of 3 years. Once the agreement was signed, Pangea began the co-designing process.

The Local Space

Photography 1. Initial photograph of The Garden that Heals´ green space.

Located in the southeast part of the property, the garden has a surface area of 500 m2 and has a direct connection with the hospitalization area and laboratory, allowing direct access for patients to enter the garden. It is also connected to an indoors space which is regularly used by hospital patients for workshops held several days a week. Its main access is through the south parking lot, which also facilitates the loading and unloading of materials in the space.

The green space is divided by cemented paths that segment the space into four main zones which met in an area similar to a central roundabout. In addition, on the east side of the garden there is a simple bamboo construction that allows a more intimate space with shade that protects from the sun.

An important characteristic is the presence of two trees of considerable size, an Avocado (Persea americana) and a Cholan (Tacoma stans), the latter being the one that dominates the landscape since it is located in the central part of the green space.

Co-design and its link to the private sphere

Pangea, a private and autonomous initiative, proposed to co-finance and sustain the execution of the project through its income, thus seeking to turn the initiative into a seed of regeneration within the city.

Regeneration (Jenkin and Pedersen, 2009) investigates how humans can participate in the development of ecosystems through the creation of optimal conditions for health in human communities (psychological, physical, social, cultural, and economic) as well as for other organisms and living systems. One of the important considerations within the framework of regeneration is the understanding of the constant flow of life, the balance within the static dimension of death, a very important concept when accepting the evolution of the system and the manifestation of its design.

Pangea works with intentional families and communities, facilitating the creation of links with their territories and the manifestation of the dreams and potentials of those inhabiting it. Its work takes regeneration as a framework of thought and action when using participatory social technologies, as well as technological tools such as drones and geo-biology to guide the design process.

The proposal developed in the space bases its design concepts on permaculture, defined by Holmgren (2002) as a system of conceptual, material, and strategic components assembled in an arrangement that allows life to benefit in all its forms. Within the permaculture proposal, it is also important to understand the need for empowering one’s self from the actions of our context in order to begin generating changes that transcend the notion of sustainability (Holmgren, 2002).

This is a fundamental reflection in the context in which we live, as humanity and as planet Earth. An old Sufi story captures the importance of our actions in this context:

There was, some time ago, a man who was recognized in his village and in the region for his wisdom.

Two young people decided to test their wisdom one day: “Let’s catch a little bird” – they said to each other. “I will ask him if the bird is dead or alive. If he says it’s alive, I crush her with my hands. If he says that it is dead, I would let her fly to prove him wrong ”. When they approached the wise man, one of the young men said: “Wise old man, hidden in my hands is a bird. Since you are so wise, can you tell me if the bird is alive or dead? The wise man looked at the boy in the eyes and with a smile said: “It is in your hands.”

Destiny is in our hands. (Mang & Haggard, 2016)

Inclusive Levels of Design

The creation of the garden was proposed as a meeting space that allowed the empowerment of elders’ health who had treatments for non-disabling diseases. The proposal initially defined some basic elements that allowed understanding the potential manifestation of the space in the development of the first stages of design; this opened the doors for the integration of new members that later became the basis of the community gardening, with whom a process of co-design and evolution was initiated. All this is crossed by the pillars of permaculture which are: governance, construction, education, well-being, spirituality, technology, art, communication, economy, and healing.

The design evaluated the following aspects:

- Climate (Internal – External)

- Precipitation patterns

- Wind directions

- Microclimates

- Movement of the sun in the landscape

- Decision-making system of the context

- Actors involved in the space

- Legal status of the intervention

- Life and soil manifestations

- Fertility of soils

- Geo-biological expressions

- Water

- Sources

- Capacity to collect and harvest water from spaces

- Logistics

- Access

- Space security

- Location of warehouses

- Biology

- Present species

- Available plants

- Biological indicators

- Environment, well-being and networks

- History

- Links with projects and donors

- Medical and psychosocial profile of the participants

- Forms of connection with the project

- Activity levels of intensity according to mood / physical states

- Constructions Support

- Structures

- Design patterns

- Energy flows (systems)

Each of the former elements was processed and systematized, which determined the basis of the design in addition to the strategies of relationship with the elders. Perhaps one of the most innovative themes incorporated is the contemplation and understanding of geo-biology.

Geo-biology or bio habitability is the discipline that studies the energies emanating from the earth and our environment, and how they affect living things. It does not belong to any strictly academic branch of science, nor does it claim to, although it takes from key concepts from geology and biology. It also collects ancestral knowledge, integrates it with the design of spaces, and materializes it in specific protocols to facilitate the manifestation of healthy and beneficial environments for the expression of life.

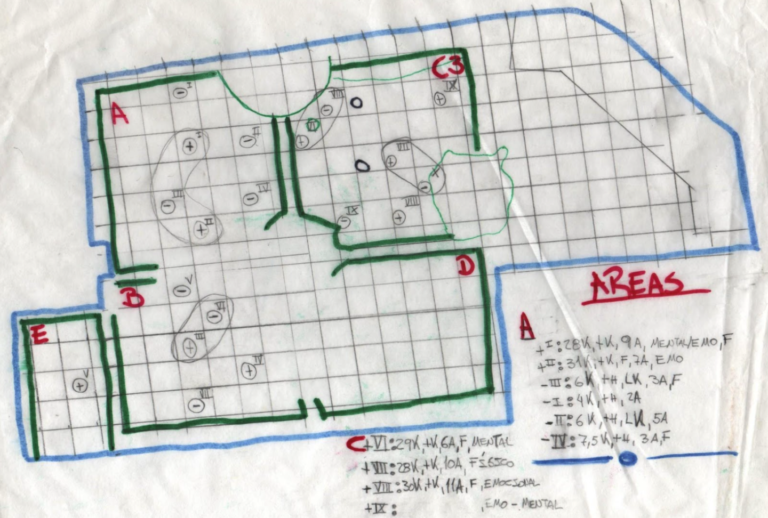

In practice, the geo-biological evaluation allowed the recognition of energetic expressions of earth by locating points that manifest places of well-being related to physical and emotional areas, in addition to allowing the allocation of suitable places to energize encounters and vitalize trails, places of importance (acupuncture of the land), plants of energy and a specifically designated space for soil regeneration.

Acupuncture of the earth seeks to channel the subtle manifestations of the entrails of our planet through trees and plants that seek to balance or amplify them in the spaces in which we intervene. This action is a form of exchange or co-creation between humans and nature.

For example, in the garden space, a point was identified where microorganisms, insects, and worms were at ease. At this point, we located the soil regeneration area (for composting) which in turn became a place of emotional venting and dedication to the earth. This process was identified as a practice based on Pangea’s research in ancestral ceremonial centers, where it was identified that the places of offerings became suitable spaces for the transmutation of the material (composting) and non-material. The material offerings were given with specific intentions and this was transmuted; therefore, in the garden, the area of soil regeneration (composting) helped to transmute emotions.

Graph 1. Map of subtle energies manifested in the space of the orchard

The former information manifested in a first design that served as a guide at the beginning of the project. As the community evolved, they took over the reins of the design, giving the process the essence of each encounter, co-design, and making community as a living practice.

The proposal included six zones with different garden designs in addition to the basic functional infrastructure: a mandala garden design, medicinal spiral garden, horseshoe design, zone of fruit trees, gallery/exhibition area, kitchen, and workshop area.

The design expressions were based on a few key elements. The first was focused on the experience within the garden as essentially therapeutic, thus breaking with some conceptions of the hegemonic system where everything must generate a material production or must be focused on esthetic parameters that do not consider the well-being of the environment and those who inhabit them. The representation of the cycles of life was also an important part of the conception in the design, with circular spaces that manifested references to the stages of it, both in spaces for the seeds and their development, growth, fruiting, and finally the transmutation of matter and the renewal of soils.

Finally, another of the fundamental elements to consider was the different emotional, physical and psychological states of those who came to the garden. Open spaces, were also included, that allowed grandparents to relax without feeling saturated by an overload of plants, colors, and smells. Alternative spaces where they could have intimate sensations that enabled them to be in the garden feeling safe and warm without the need or obligation to interact with other members of the community. Rest and interacting spaces were also available, as part of the design, for those who searched for an opportunity to do so. All these considerations were put into practice due to their relation with the proposed activities, dynamics, and rhythms of work within the garden.

Graph 2. Map of the garden’s final design

Opening of the space

Socializing the Proposal

The socialization of the first design began in March 2019 in the hospital auditorium where all those interested in the proposal to build a garden within the green space were summoned. Two sessions were held to share the proposal and receive feedback in addition to motivating the active participation of those who were interested. An average of thirty elders attended these socializations.

In the field, the work began with a group of fifteen grandparents with whom the Mandala Garden was developed. Its main characteristic was a representation of the cycles of life through the circular ditches divided into four sections: the first dedicated to the sowing and care of seeds of different species, followed by an area focused on ornamentals and perennial crops, a section for short-cycle crops and an area dedicated to the recycling of nutrients and soil life.

Caregiving as pedagogy - Relationship dynamics

Photograph 1. Members of the community in front of a mural dedicated to them

A day in the garden included various group dynamics:

- 9 am – Don Segundo, one of the first members of the community who has an especial relation with nature and has been part of many community projects, was already in the garden because he always arrived an hour earlier. He would circle around the space but did not launch himself to star working the field.

- 10 am – Volunteers arrived along with grandparents from the garden, people outside the hospital, among others. They gathered in a circle to share the first words and with that start the day.

- Daily activities included: exercises to warm up and stretch the body, group shoulder and back massage in a circle to loosen tensions. “Karate”, a game with postures, shouts, and martial art movements replicated to energize the body. Here the participants get a chance to socialize what they want to do for the day and what they are not willing to do.

- Everyone participates in the decision-making process of what should be done and how to do it, based on what is needed. In order to include community members in this process certain questions are asked such as: What should we sow in this part? Are we going to move the compost? What color of thread should we use for Grandpa Cholán’s (the guardian tree) sweater today? This last question referred to an activity of weaving a sac that was placed on the guardian tree every Friday.

This moment was key in the construction of governance and co-design. It is here where the intentions, desires for action, autonomy, and the willingness to care, were gathered and later put into practice. This process also entails human/nature facilitation and companionship.

- 10:20 am – Each one took their gardening tools and set off to do their job. The activities are diverse depending on the day. Some days they consisted of removing herbs and earth, germinating seeds, pruning plants, weaving the sweater of the grandfather Cholán tree, and so on. These activities were organized as mini workshops and spaces where everyone had the opportunity to share their knowledge.

- 12:00 – Sharing or food depending on the day or just saying goodbye.

This was the general ritual; every day we started like this and little by little, as more people gathered, activities were added. Sometimes they brought food, life stories, photos taken by the local media, and more.

The unfolding of this process allowed us to identify ways in which rituals are created with a purpose, they respond to the place, people, and activity, shaping the social dynamics that will embody the experience in the garden. All these practices manifest a pedagogical experience based on caregiving and the empowerment of wellbeing and its relationship with spaces.

Perhaps an element that we think may be interesting to delve further later is in relation to the configuration and learnings of the space-territory with the Andean cosmo-living. This is due to the fact that in Ecuador 14% of the population is indigenous and in cities like Quito this representation is invisible due to the various causes explained above that bring the logic of modernity. However, the territory speaks, the mountains manifest themselves and it is in the interaction where certain traditions accompany the doing and the community practices are part of the cosmo-living that we maintain as Andeans, and it is the legacy of the ancestors. In Quito, the majority of the population is mestiza, which is the mix between Spanish, Afro-descendant, and indigenous traits-ancestors. This triad within the social configuration has different representations that are shown in the interaction. One of the most predominant manifestations is related to the fact that the mestizo is intertwined with the urban, with the cities and mark a rhythm of life in relation to the systemic logic in which education, the social, and the cultural are presented.

It would seem that within spaces where the community is configured as part of the social dynamics, these messages of the territory emerge again that invite us to return to the nature of the Andean, to meet the culture of mutual care as the nucleus of community life, such as Ayllu was understood. This is based on love and its different branches, such as compassion, care, protection, security, sharing, reciprocity, work, and empathy. For the indigenous peoples of this part of the world, the caregiver practices a form of compassion.

The bond of caregiving and Andean living cosmology

In Ecuador, 14% of the population is indigenous and in cities like Quito this representation is made invisible by the logic of capitalism, globalization and modernity brought to us by the social, economic and political processes that we are part of. However, the territory speaks, the mountains manifest themselves and through this interaction of people with their landscape, certain traditions accompany community practices that are part of the living cosmology maintained by us, Andeans, and is the legacy of our ancestors.

Andean ancestors built a culture of mutual care as the nucleus of community life known as the Ayllu. This care is based on love and its different branches, such as compassion, caring, protection, security, sharing, reciprocity, work and empathy. For the native peoples of this part of the world, caregiving practices are a form of compassion. Care encompasses human and non-human beings since within this living cosmology we are all part of the whole and respect encompasses all forms of existence.

In the garden, this mutual care was an essential part of sharing, it is one of the elements that aroused naturally for those who attended. Spontaneous moments of sharing, bringing food, talking, laughing, getting upset, became key parts of the exchange.

Why caregiving as a pedagogy for the garden that heals?

The forms of learning lead us to practices that revolve around the creation of possibilities and the construction of knowledge rather than its transmission (Knowledge from Paulo Freire -Pedagogy of freedom). Learning spaces outside the regulated system invite us to become more and more humble, to understand learning as an exploration, a life experience and an invitation to pay attention to our senses, territories and our relationship with what is not human. While in the educational system, schooling, modernity and the logic in which we seek to inhabit the world tells us how to learn, the invitation in the healing garden is to awaken the senses, exercise autonomy, and experience doing and sharing.

Learning, as Munir Fasheh mentions, is a biological act, it is part of our path, it is like food for our bodies, it is part of life itself. How we organize our inner world, our life, the stories that we tell and share, involve us in territories of exchange of what we are through sharing with others. Each detail in the process shows an interpretation of how community building and learning (through the Healing Garden) can be a path for regeneration. This was put into practice at the Elders Hospital for Integral Care, the approach to those who administer it, the planning, the co-design, the feedback, the link with permaculture, the stories, the sharing, the elderly, the living and non-living elements, all that was learned and experienced.

Expanding this vision of the biological act we find that the relationship with the non-human is essential for the construction of a caregiving pedagogy at the garden. The approach to understanding the expression of earth’s energy and its relationship between humans and non-humans has allowed reinterpreting ancestral practices and ties with the territory to facilitate the wellbeing of those who interact and bond in the garden. These subtle energies allow certain expressions of both microorganisms (fungi, bacteria, actinomycetes, etc.), elemental beings (salamanders, undines, gnomes and fairies), and even the influence of physical, mental and emotional aspects of people can find expression in a dynamic that is directed towards free oscillatory equilibrium in the places of interaction. Contrary to community learning processes, the dominant educational logic/dogma limits the expression of life through, static, controlled and artificial equilibrium.

A path to regeneration; social wellbeing in practice

A common problem elders have to deal with in the city is people forgetting about them. My grandmother used to sing a song that said: “in life, you should love me, because when I am dead it would be too late” She referred to this as a complaint about how she felt forgotten, that people and family members did not visit her often. This is an example of a request for attention in the present moment, and how there is an imaginary that is embodied in the elders around the idea that they are being forgotten. By keeping this situation in mind, caregiving was manifested and expressed as the natural response required for the configuration of the community in the garden.

The situation of many of the elderly who were in the garden is related to stories of abandonment and lack of accompaniment. Therefore, in this space, they were able to find an activity that would make them smile, do things, take care of the plants and share. It is in their actions and “doing” that they go once a week to the place where the fruits of their interaction with the land, the rhythm of the activities and their own will to take care of the place are at stake.

There are various stories to share and unravel in order to explain how a pedagogy was formed around this reality of elder´s solitude:

Doña Anita Almeida, 69-year-old, mother, grandmother, farmer, lives in Pululahua, a passive volcano located 2 hours from Quito. Doña Anita tells us that she had to go to the hospital because she had a leg problem and for her rehabilitation, they recommended that she opted for an activity to complement her therapy. Among the options offered by the hospital, which are: dance therapy, embroidery, laughter yoga, reading club and the healing garden, she chose the garden. Anita goes with her daughter-in-law and sometimes with her 7-year-old granddaughter to weave Grandpa Cholán’s sweater or to weed the land. Her daughter-in-law told us that before coming to the garden when they called Doña Anita over the phone, she used to mention feeling very depressed and sad to be so alone. Now, even after finishing her physical therapy, she comes to the garden with her family every Friday. This is her activity of the week where she can socialize, laugh, and share her knowledge about the land. She is a farmer, she is the advisor on which plants to plant in “skinny” soils, the planting distances, how to make the furrows, she is the one who has taken care of the small plants and she is the one who has dedicated the most to the weaving for Grandfather Cholán’s sweater.

Weaving a sweater for the tree was an activity proposed as an alternative to working with the land, which can be more physically demanding. Grandfather Cholán’s weaving gave the place beauty, an opportunity for sharing of life stories, laughter and tears. This action gave Grandfather Cholán an identity within the garden and materialized the idea of sharing stories called “From the roots”. Volunteers who came to the garden approached Grandfather Cholán to share stories, to sing their songs to the seeds, the earth and the sun. One of the visitors, Suanua Maiche, from the Shuar Kuamar community of the Ecuadorian Amazon, came to the garden and shared stories about her grandmothers. Thus, Grandfather Cholán emerged as a character in the garden and gave life to the story of Uruchnum, a woman who became a medicinal tree of dragon’s blood that heals wounds and diseases.

Link to the video of the story here: https://youtu.be/PSmeJXqMXdA

This framework is an example of the manifestation of fertile land: they are the flowers and the fruits that are gathered from an experience of regeneration.

Another story of caregiving practices born in the healing garden is about an avocado tree that was at the Hospital’s green space before the garden was co-designed. This tree was dry, overgrown, and lacking in nutrients. Months after the exercise of caring for the garden, paying attention to the ground, bringing more beings to the space, the avocado tree started to shine being nourished by the tissue that generates a relationship for the exchange of activities, knowledge, energy, learning and unlearning.

The place, as mentioned in the design of the physical space, was intentional in each step, it was thought in great detail, with the acupuncture of the earth, with the vision of the design that allowed a safe place to share, to do, to be and to care for.

Conclusions

The process that is reported in this article begins with a seed question brought by Pangea.

How does regeneration take form inside a city?

The process of the healing garden brought some light to this question and there are several elements to name and to make sense of them an experiential component is required, but we want to summarize the caregiving pedagogy as part of a regeneration process with three key elements:

- Learning how we relate with our territory; the deep relationship between what is alive now and the ancestral origins, together with the community that inhabits the space gives a particular learning experience.

- The notion of the non-human as an important factor within the pedagogy and geo-biology as a means to understand and connect with everything subtle that manifests and interrelates from the earth.

- Pedagogy as a biological act and as a way of relating to the world in awareness of the constant and necessary learning that occurs in our landscapes.

The manifestation of the above, even in a small space like the garden, brought us close to a nurturing flow where all the members of the community, humans and no humans, where in a state where we can say its closest to life and we can only empirically imply that in doing so a healing process begin to emerge. We were witnesses of how human relationships were mirroring the care put in the garden, and these relationships began a feedback process where diverse manifestations emerge and improve the inner and outer landscape of the community. Further information and investigation with a holistic point of view are required to shed more light on this process.

Our goal with this document is to promote experiences like these, where nature is encompassed, the intangible, the ritual, public entities and the will of young and elderly people that can create spaces of transition becoming examples and living alternatives of higher education.

We shared some elements to other initiatives around our planet Earth that are willing to start with regenerative processes. In addition, this social laboratory leaves a possible configuration between state, private initiatives, community, and volunteering as a possibility of action in the territory and from within.

Finally, we want to underline that elders are a population that can be taken into account for alternative educational processes with the aim of reintegrating their presence into society, retrieving their place as wise old women and men from whom we can learn.

Audiovisual Gifts from La Huerta

Stories from la Huerta: Uruchnum y el árbol de sangre de drago

A project to rescue stories, knowledge and experiences from the Healing Garden. Abue cholan connects with a community in the Amazon of Ecuador who tell him the story of how the sangre de drago tree was created.

Bibliography:

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of freedom: Ethics, democracy, and civic courage. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Mang, P., & Haggard, B. (2016). Regenerative Development and Design. 274.

González Ollino, D. (2018, noviembre). Datos y estadísticas para monitorear el avance de los ODS en los temas de envejecimiento y personas mayores (ODS 17.18). Presentado en Reunión de Expertos sobre Envejecimiento y derechos de las personas mayores, en el marco de la Agenda 2030 para el Desarrollo Sostenible.

Prest, J. M. (1988). Garden of Eden: The botanic garden and the re-creation of paradise.