By Sangeetha Sriram

The real purpose of education is to serve life and enable meaningful living and bringing out the highest potential in people; fulfilling and dharmic livelihood is one among its many dimensions. But we now live in a world where an insatiable and destructive capitalist economy has come to exist for its own sake, and almost all of education is being designed to serve this cancerous growth. The current industrial system of education is churning out unimaginative degree holders (1), pushing them into what we might as well call ‘deadlihoods’, sucking them dry of their agency and creativity, and touting consumerism as the cure for the lack of joy they experience. It is clear that we need a radically new vision. And thankfully, beyond the field of mainstream capitalist education, there are ecoversities which are reclaiming diverse knowledge systems and reimagining new approaches to higher education that are inspiring and preparing young people for ‘alivelihoods’, occupations that help them and the world heal, come alive and thrive! And there is an urgent need for Ecoversities to bring to the heart of their conversations and practice, a radically new vision for the economy and embodied experiments to actualise it. Auroville, an international, intentional community (located in Southern India) where I reside, that aspires to be a learning society that is at once a university as well as a city where learning happens in live-in laboratories, offers some insights into how this can happen.

Over the past couple of years, I have been part of a weekly study circle in Auroville with others who held similar questions and aspirations which we explored at three levels: the personal (our individual journeys, struggles and insights around money and wealth), Auroville ( the collective journey of Auroville in the economic realm and lessons to be learnt) and the larger systemic (what new models can we offer through our work here to creatively challenge and dismantle the already obsolete and crumbling global financial system). This essay lays out the process in the following four distinct sections: the personal, the collective (Auroville), the National (Vikalp Sangam), the Global and an aspiration for the way forward to weave them all together.

I – THE PERSONAL

Over the past year, The New Economy Study Circle met every Monday morning over a community breakfast of idlis and vadas, plenty of laughter, and serious conversations around our insights on what we meant by ‘the new economy’. Every week, one member shared their understanding of the ongoing capitalist economic crisis, their personal journey and their vision for the new economy. When we realised that we had a shared understanding of the nature of the crisis (2) and since we had all individually already spent many years trying to understand how the dehumanising market system worked at the global and national levels, there was a collective need to deep dive into the other end: the personal, which we felt was largely unexplored. If we want to be part of creating a larger system that is based on abundance, the quality of the most fundamental building blocks (i.e. individuals) becomes very critical.

We had each been part of collectives where individual members, without having a deep personal commitment to looking at their own fears and insecurities and habitual behaviours around money, attempted to “change the system out there”. Since our experience in these spaces had been dissatisfactory and shallow, and sometimes even led to a collapse of the experiment itself, we decided that a non-negotiable qualification to be part of the circle would be a willingness to sincerely share our questions, dilemmas, self-discoveries, dreams, shame, arrogance, fears, aversions and desires (around how the money system affects our inner worlds) as they arise at different points along our journey; and the ability to laugh at oneself at the end of the day! The group believed that deep change needs to be simultaneously personal and political; that unless we bring our inner worlds into the game, we cannot change how it operates in the various layers of the outer realm. We did a few experiments around this.

We had each been part of collectives where individual members, without having a deep personal commitment to looking at their own fears and insecurities and habitual behaviours around money, attempted to “change the system out there”. Since our experience in these spaces had been dissatisfactory and shallow, and sometimes even led to a collapse of the experiment itself, we decided that a non-negotiable qualification to be part of the circle would be a willingness to sincerely share our questions, dilemmas, self-discoveries, dreams, shame, arrogance, fears, aversions and desires (around how the money system affects our inner worlds) as they arise at different points along our journey; and the ability to laugh at oneself at the end of the day! The group believed that deep change needs to be simultaneously personal and political; that unless we bring our inner worlds into the game, we cannot change how it operates in the various layers of the outer realm. We did a few experiments around this.

‘Money on the Table’, for example, was an experiment where, once every two weeks, everyone placed on the table any amount of money that they felt called to. Two of the Circle members’ names got picked randomly through lots. They took the fund to come up with any way that they would like to use it to seed the new economy of their dreams and share their experiences and insights at the next meet. The key thing was for everyone to share their experiences all the way from pulling out cash from their wallets (Am I offering too much or too little? What will others think of me? Do I feel scarce? Am I being calculative?) and offering it to the collective, to what they learnt about themselves and their relationship with money. An experiment that came out of this was the semi-spontaneous ‘multicolor wealth exchange’ (recognizing and sharing multiple forms of wealth) in a public place in Auroville.

One member led the process of creating a repository of resources (books, essays, films, podcasts, games, etc.) which explain the fundamental dysfunctionalities of the old system, as well as inspire imaginations and possibilities for the new.

At the next level, the Study Circle attempted to study Auroville’s journey in economic reorganisation.

II – THE COMMUNITY

Auroville’s Vision and Founding Principles

"The aim of its economics would be not to create a huge engine of production, whether of the competitive or the cooperative kind, but to give to men—not only to some but to all men each in his highest possible measure—the joy of work according to their own nature and free leisure to grow inwardly, as well as a simply rich and beautiful life for all”.

Sri Aurobindo

Such is the loftiness of the dream on which Auroville was founded half a century ago by Mirra Alfassa (fondly called ‘The Mother’), the spiritual companion of the Indian seer Sri Aurobindo. Since then, about 3,000 people from about 56 different nationalities have moved into this evolving ‘City of the Future’, many of them drawn to the ideals described in its founding texts: The Dream, The Auroville Charter, and To be a true Aurovilian.

Our starting point, both in Auroville and the world at large, is a context that has it the other way round. Instead of the economy serving society, and all of Life for that matter, we have all aspects of life – education, culture, health, knowledge, art, religion, polity – being made to serve the economy, a dysfunctional, parasitic system that has lost its soul and its way. The purpose of Auroville is to develop as a spiritualised society, in which The Mother envisioned a new way of being and living, laying down several economic principles for the township to experiment with:

“All wealth belongs to the Divine and those who hold it are trustees, not possessors… Auroville belongs to humanity as a whole, its residents are only its caretakers. For a conscious use of matter, there is no need for the sense of personal possession… Auroville is the ideal place for those who want to know the joy and liberation of no longer having any personal possessions… All is collective property to be used for the welfare of all.”

“The spirit of competition is to be replaced par the spirit of cooperation based on a sense of mutuality, coming from a sense of inner unity. It is the responsibility of each individual to give sense in his life and work to the notion of “change of consciousness”.

“Work would not be there as the means of gaining one's livelihood, it would be the means whereby to express oneself, develop one's capacities and possibilities, while doing at the same time service to the whole group, which on its side would provide for each one's subsistence and for the field of his work.”

“Money is not meant to generate money; money should generate an increase in production, an improvement in the conditions of life and a progress in human consciousness. This is its true use… [Money won’t be used in Auroville] Auroville will have money relations only with the outside world. And one does not have to pay for one’s food, but one must offer one’s work or materials; those who have fields for example, should give the produce from their fields; those who have factories should give their products; or one’s labour in exchange for food. That in itself eliminates a lot, the internal exchange of money… In reality, it should be a township for study and research in how to live in a way which is at once simplified and wherein the higher qualities will have more time to develop. Those who produce food will give what they produce to the town and the town is responsible for feeding everyone. That means that people will not need to buy food with money; yet they must earn it.” (emphases added) (3).

Through my own journey as an activist over the past two decades, in my attempt to understand the nature of our civilisational crisis, I had arrived at exactly these ideals. So had our Study Circle members. These, along with the larger vision of Auroville which aspires for human unity and Integral Yoga (bringing together matter and spirit) had drawn us here. Like us, since its founding 50 years ago, several Aurovilians have gathered here from different cultures, inspired by these founding economic principles, have experimented with various modes of economic organisation and practices, attempting to create a trust-based, collaborative economy. Here are a few that we found to be the most significant among them all:

1. Ownership

There is no private property in Auroville: land, all immovable assets (including homes), and community enterprises are owned by the collective. Aurovilians may be stewards of an Auroville home, but they cannot sell it (even if they have financed it) or even bequeath it; they can only exchange it for another housing asset within Auroville. Similarly, there are no owners of Auroville enterprises. Even those who have set them up, and usually invested the start-up capital, are only executive managers. They cannot sell the enterprise, neither to another Aurovilian, nor to a non-Aurovilian. If they choose to step down, a community body called the Funds and Assets Management Committee (FAMC), approves new executives. Some enterprises are run by a small team of executive managers, while others work along the principles of a co-operative. For example, the Auroville Arts Service is an co-operative of 67 Auroville artists, through which they sell their artwork, and contribute to the service on a voluntary basis.

2. Forms of sharing

Community Funds: Income-generating enterprises fund a communal budget, which is allocated across various ‘service’ sectors of the community (farms & forest, health, education, arts, municipal services, etc.) by a group of their representatives. This developed from the Envelopes system through which funds were distributed in the earlier years of the community, when there were very few community services. Representatives of different settlements within Auroville placed their needs in regular community meetings, and disbursements were made through a collective process. The communal budget also funds Maintenances, monthly financial and in-kind support for Aurovilians (awarded on the basis of their workplace and their level of need).

- Common Accounts: in Auroville there have been many experiments (some abandoned, some continuing till date) with common accounts, such as The Circles experiment, a large-scale community mobilisation in the early 2000s to encourage many members of the community to participate in collective accounts projects, based on the success of a couple of previous experiments (Seed and the Common Account). Each collective accounts project group decides its own principle of functioning. While many have failed or have been disbanded for various reasons, some collective accounts projects last to this day. This active experimentation has provided for a valuable natural learning experience. Some of the successful projects that pool member contributions are Nandini (a clothing and tailoring service), and the Pour Tous Distribution Centre (PTDC), an internal distribution centre primarily for food. Collective contributions meet the cost of operations, irrespective of individual members consumption and payment, and there are no prices on products, encouraging members to take what they need. There is a periodic reconciliation that shows both the contribution and consumption allowing for the member to re-adjust subsequent contributions or initiate a conversation that allows for them to share their monetary ability.

- Sadhana Forest, Pitchandikulam Forest, Botanical Gardens, Pavilion of Tibetan Culture and Sacred Groves are communities and projects that have extensively embodied various forms of gift culture, freely sharing knowledge and resources, relying on donations made by well-wishers and their own income-generating activities, from both outside donors (in the form of money) or internally among members of Auroville who share other forms of wealth.

3. Forms of exchange:

- In AuroOrchard, a farm that supplies fresh produce to many communities and eateries, labour can be exchanged for fresh produce.

- Aura, an online marketplace where needs and offers are exchanged, is in its experimental phase. It attempts to bring together the idea of Universal Basic Income and alternative currency.

4. Forms of wealth

Instead of a universal basic income, there has been an attempt towards realising universal basic services in the following forms:

- Natural wealth: Auroville’s land itself is a huge source of natural wealth. From the early years, community members have invested in what is today exemplary environmental restoration through afforestation and water conservation, reviving a once barren landscape. Projects like the Auroville Botanical Gardens and forest communities like Pitchandikulam preserve and propagate valuable vegetation and disseminate knowledge about how they can be used for human wellbeing. Roots is an initiative that helps residents to rely on the natural wealth of Auroville through forest walks to identify wild edibles, forest foraging and gleaning sessions, workshops on making cleaners like tooth powders and bio-enzymes using locally available natural materials, etc.

- Knowledge wealth: Access to schools is free for all the resident children. Auroville is a place with an abundance of learning opportunities for children and adults with workshops on arts and craft, music, theatre, movement, facilitation, healing, yoga offered throughout the year. Many of these are subsidised by the communal fund, offered in the spirit of gift, or for a voluntary contribution.

- Material wealth: Auroville has a Free Store, where residents offer items that they have in excess of their need – clothes, footwear, crockery, books, toys, accessories, etc., and anyone can take these for free. A-LoT (A Library of Things) is a place where things could be donated / lent to and borrowed from.

- Social wealth: Opportunities to participate in weekly potlucks (or eat daily at Auroville’s community canteen, The Solar Kitchen), community gatherings, workshops and governance processes (in various flavours) abound across Auroville. While the Resident Assembly Service (RAS) attempts to involve the residents in governance, experiments like Integral Entrepreneurship Lab (IEL) attempt to tap into the collective wisdom and wealth to build synergies. Spaces like Youth Centre and Youth Link enable youth to connect with each other and express their imagination and creativity.

- Spiritual wealth: There are plentiful opportunities for spiritual nourishment and growth, from quiet time in nature to meditation halls, healing spaces, nonviolent communication practice groups, discourses and workshops on Integral Yoga.

- Health wealth: Quiet Healing Centre and Verité offer free services to Aurovilians, and finance their operations from the income generated through service to the guests and the Auroville Health Fund Insurance Scheme. Pitanga offerings are subsidised by Auroville’s communal fund. Many individual healers working independently from these centres offer their services to Aurovilians on a gift basis as well.

- Cultural wealth: One of ‘The Dream’ statements says “Beauty in all its artistic forms, painting, sculpture, music, literature, would be equally accessible to all”. Auroville offers abundant opportunities to access this form of wealth with the experiment being located in the rich soil of ancient Tamil culture, the active engagement of people from 56 countries and through various countries / cultures having their own Pavilion that showcase the offerings from that region. All performances and cultural events, including daily film-screenings are open to all residents and visiting guests alike; free of cost, many paid for by the communal fund.

- Financial wealth: Auroville generates financial wealth through its income-generating enterprises (within Auroville for residents at a discount, or for guests and visitors, and outside supplying to shops and boutiques); receives recurring government grants for educational research, donations from individuals (Aurovilian and non-Aurovilian), foundations (such as the Foundation for World Education, and Stichting de Zaaier), or CSR funds for specific community projects.

Gaps & Challenges

Auroville is a unique experiment in that it is among a very few places in the world, where people from so many different cultures have attempted to live together in such numbers on such a large land area, and managed to sustain it beyond five decades; and all this in the spirit of co-creation without the direct instructions of any single leader or ‘Guru’. The Mother’s vision statements are treated mostly as guidelines that are constantly revisited in order to see what they might look like in practice in the present context. While this does make Auroville very welcoming of new social experiments, and while we do have such a wide variety of economic experiments that have been made over the past many decades, in an overall sense, the discourse and form are very far from being radically different from what one sees in the world outside. And here are some reasons for why it might be so.

- The economy is almost entirely based on money, apart from the monthly ‘maintenances’ offered to Aurovilians, which are offered partly in kind.

- Studies say that only 15% of the food needs of Auroville are being met by what is grown locally. The situation is similar in the case of other common products made here like soaps.

- Though the monthly financial and in-kind support is sufficient for a simple lifestyle within Auroville, it is hard to accommodate financial savings or other kinds of expansions in one’s life, including visiting families in one’s home country.

- Though there might be some evaluation of economic initiatives, there isn’t a process to continually assess whether and how these are engaging with Auroville’s economic ideals, in order to inform and encourage future practices. Review of commercial units is restricted to mainly mainstream metrics and financial returns. When compared to fields such as art, farming, healing and design, there is relatively little research, experimentation and documentation that happens in the field of alternative business and economics.

- Commercial units hardly interact, share resources or work towards building synergies, while the possibilities of doing so given the proximity of the units and the shared values, are enormous.

- Much of what is being offered without a cost or on the basis of gift is often cross-subsidised by charging the guests and visitors to Auroville a high price. This leads to perceived elitism and economic exploitation by the businesses in Auroville.

- Since the Auroville economy still deals with mainstream currency (rupee) as its primary mode of exchange, the investments are being made in global banks contributing to and strengthening the larger exploitative financial system which is embedded within the idea of debt and scarcity. The economy still relies on grants from the Indian Government and international donors.

- The local villagers are still largely employees of various commercial units within Auroville, although exceptional ones are actively co-shaping the larger experiment and discourse within.

And there are a number of challenges that come in the way of reimagining and taking decisive steps forward in the direction of our ideals.

- Lofty ideals can be a blessing and a burden, simultaneously. They are a blessing when they serve as an anchorage and a reference point. They turn into a burden when they set us up for failure and endless self-criticism. The feeling that nothing-but-perfection-is-good-enough creates an unhealthy atmosphere of insufficiency, and sometimes inertia.

- This being a melting pot of many world cultures and the local village culture added to the mix, there are various perspectives that need to dialogue with each other in order to arrive at any consensus. This makes decision-making often a long-drawn process, coming in the way of taking decisive steps forward.

- Attempts to build and maintain bridges with like-minded groups outside are few and far between. Apart from personal connections, there is a rudimentary contact with academics studying alternative economy models. Information is not very systematically shared, stored and used.

- Though, of late, structured programs are being offered to bring new members up to speed with the intricacies of the Auroville model, there is still a long way to go towards enabling smooth entry into the often confusing and contradictory reality.

While there are more details and nuances to these gaps and challenges, when such chaos and pluriformity can be embraced with curiosity and acceptance, they transform into a rich field for study and experimentation, both of the system and of the self. Through our study, we collectively arrived at what we call ‘The Integral Economic’ model.

Exploring an ‘Integral Economy’ for Auroville

Through our study and collective contemplation, we realised that the emerging economy needs to be integral in two ways. It needs to integrate the personal and the systemic. It needs to be a dynamic meta-form that can accommodate different models in a way that they can all co-exist with, converse with and support each other.

Integrating the personal (the yin, interior) and the systemic (the yang, the exterior):

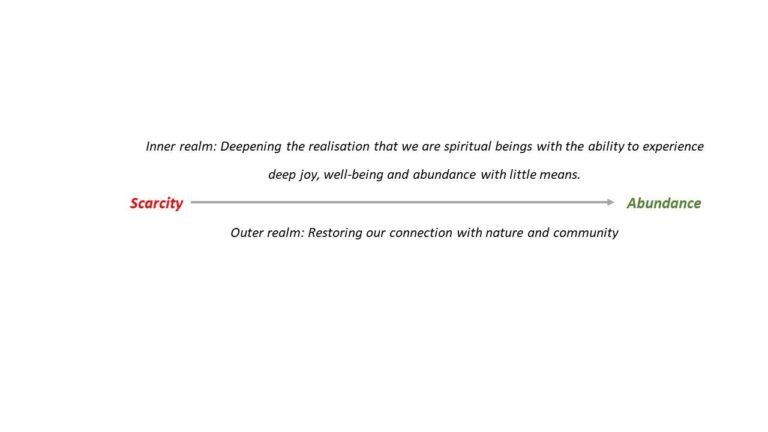

Imagining and creating new economic models primarily requires a move from the illusion of scarcity to an experience of abundance; a shift that needs to occur primarily in our inner worlds which will then reflect in our outer worlds. In the inner realm, an experience of abundance springs from an increasing realization that we are primarily spiritual beings having a human experience, and are capable of experiencing a deep sense of contentment, joy and aliveness with very little material means. In the outer realm, an experience of abundance springs from increasingly restoring our lost connection with Nature, our Mother and sustainer, and with fellow beings, and designing our social and economic structures on the basis of this shared intimacy. With some work to acknowledge, embrace and address our collective blind spots and structural inefficiencies, we realised that Auroville is probably among the best-placed communities to actualise such a shift in scale.

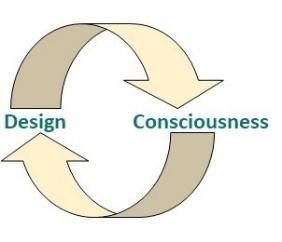

Designing new experiments in economic organisation based on trust and collaboration is like opening small windows in suffocating closed rooms filled with the air of fear. The opening of these windows can be transformative, help people see and experience what is beyond their limited selves and belief systems. But these experiments themselves can sustain, thrive and deepen only if the participants then pick up the cues, and make their own effort to open more small and large windows and doors and step out of their rooms, eventually breaking down their garden fences, creating newer ways and greater depths of communion and co-creation. This requires continuous inner work and expansion of the sense of self. Thus, designs can create powerful transformational fields that can inspire a shift in consciousness. Deeper shifts in consciousness can in turn further radicalise organisational designs.

Integrating different models of economy

Sri Aurobindo developed the praxis of ‘Integral Yoga’ which synthesised the different forms of yoga and that served and integrated all the different levels of the being: the physical, the vital, the mental and the spiritual. The physical being is limited to the realm of form and matter. The vital is the realm of the animating energy (prana). The mental is the realm of the rational, discerning intellect. The spiritual constitutes the ranges immediately above the normal human rational intelligence. In general, it may be called intuitive.

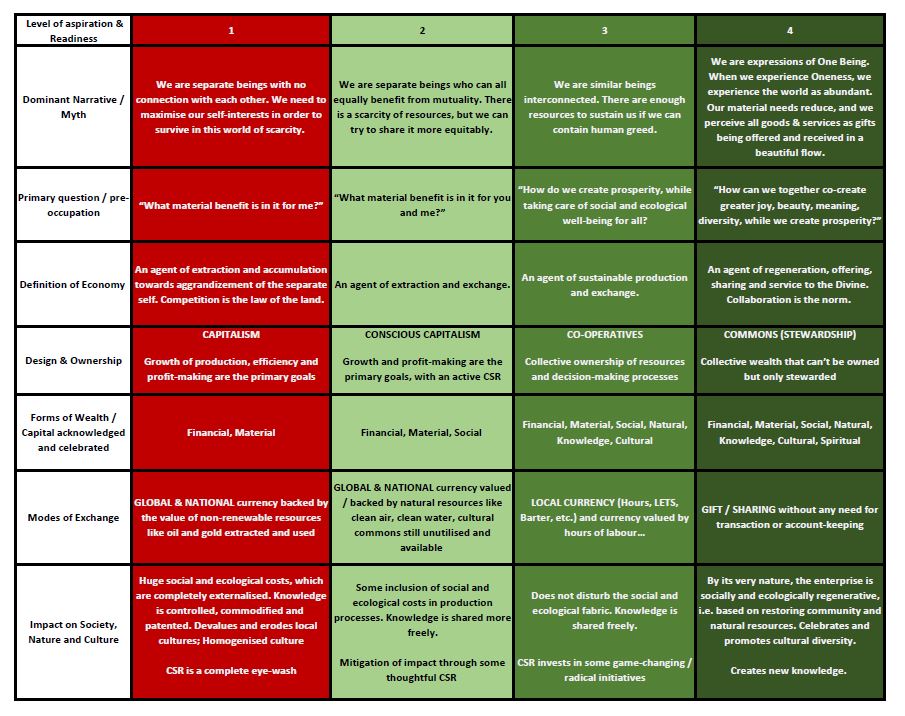

Here is a matrix to understand the different universes that are anchored in these different realms of consciousness. Each of them embodies a different level of aspiration and readiness for adventure, trust and collaboration. The current dominant materialistic worldview which has given rise to the system we have is represented in red. The emerging worldview is shown in different shades of green.*

From our study of Auroville as a system and its experience so far, we realise that there can’t be a single solution for all. What is appropriate for one actor may not be for another. What is appropriate at one time may not be at another. What is appropriate in one context may not be in another. And all these three factors (actor, time and context) are constantly in a dynamic process of coevolution. What then makes sense is to imagine and create a many-layered economic model; an Integral Economy, where multiple experiments in valuation, ownership, sharing/exchange and decision-making can happen simultaneously (ensuring that they are not at cross-purposes), each serving a different level of intimacy and readiness. Even when we have moved to a form of economic system where we are primarily offering and receiving gifts, in our globalised world, we will be sharing our gifts across a wide spectrum of people: from those whom we know really closely, to those we don’t know at all.

* At the level of a family or a close-knit community, there is a deep level of trust to recognise everyone’s gifts and that they will be offered whenever and wherever possible and needed. Sharing our gifts with this level of trust, has no need for a system of tracking or account-keeping, and hence for any form of currency.

* At a slightly larger level of the village (or a cluster of villages) with a thriving local economy, local forms of currency like ‘Hours’ or ‘LETS’ or ‘Barter’ will be needed. Local currencies are a way of ensuring that our resources circulate locally.

* At an even larger scale of society, where we get products from places as far away as other continents, we will need to use a common global currency, preferably networking with sister initiatives.

In this model, each person can choose to plug into, experience and co-shape any of these multiple experiments depending on their reality and readiness, and keep modifying their choices along the way.

The shift from the mindset of scarcity to an experience of abundance is something that can happen neither overnight, nor in a linear manner. It can be most pragmatically envisaged as a dabbling with different forms and experiments at different points in time and in different contexts, and also depending on the intimacy of the circle of connection itself.

In an initial attempt to visually depict the Integral economy, we came up with these concentric circles on the left side. But it is very likely that the drawing on the right, with an organic, sometimes clumsy, emergence of experiments in all shades of green, is what we will see. It’s a drawing partly conceived and drawn by a nine-year old who listened to the idea of an integral economy explained to her.

III – THE NATIONAL / GLOBAL

The conventional economy of Auroville is heavily connected to the larger economy in terms of inflow of money (through loans and grants from governmental and non-governmental organisations, private and corporate donors) from India and abroad. These funds have been used for research, development as well as for asset creation. Many products made in the commercial units in Auroville rely on export markets, both national and global in scale. Apart from these, money from the system is also invested in the global banking system. While this is at the systemic level, individual Aurovilians also rely on sources of personal financing from their respective countries, by working there for part of their time, getting support from friends and family based out of there, or from their personal finances invested there. Though this hasn’t been carried out yet, a more holistic study of Auroville as a system would need to sense into and analytically understand these larger connections as well, both qualitatively and quantitatively.

The alternative economy of Auroville is also connected to the growing movement of alternatives in the realm of economics both nationally and internationally. Members of the study circle recently hosted the ‘Alternative Economies Vikalp Sangam’ which is a pan-India network of alternatives engaged in creating systemic alternatives. 80 members from across the country came together for four days to share their work, dreams and ideas for the new economy and foster collaborations. In May-June 2020, some members had planned on undertaking an over-land travel as part of the Green Silk Road, as a response to the crises of global warming and cultural erosion. The group had planned to journey through and collect different stories of economic alternatives all along the way from India through Iran, Turkey, Balkan to Spain (Barcelona) to participate in the World Social Forum of Transformative Economies (WSFTE). (However, due to the coronavirus pandemic, the journey had to be cancelled.)

THE WAY FORWARD

The Study Circle was initiated by a few of us who are rather new to Auroville, ranging from two to ten years of residency here. Over time, the circle has slowly grown to include some community elders who have engaged in economic experiments here over decades. Our Circle is evolving into an interesting inter-generational group, bringing together the gifts of experience-based wisdom and those of fresh ideas and energies. There are a few ways we are looking to continuing our work forward.

Currently, much of the discourse and its related experimentation remains limited to Auroville, often inadvertently excluding the local villagers who have played and continue to play a significant role in its economy. The first step is to redefine our area of work from ‘Auroville’ to the ‘Kazhuveli bioregion’ which is a collection of villages in the Kaluveli watershed area including the growing city of Auroville, and connect deeper with our larger cultural and ecological context.

Though there are many initiatives that have been working towards this new dream and several attempts at creating collaborative spaces like the IEL (Integral Entrepreneurship Lab), there is still a huge untapped potential in this area. The second area of work is therefore to create spaces to further the dialogues and collaborations to fill these gaps.

Os third step is to continue to experiment with increasing local production and consumption, farmers markets, local currencies, community funds for seeding local sustainable enterprises committed to serving the Kaluveli bioregion.

Os fourth and probably the most important step is to reimagine learning spaces and involve children and youth in this whole exercise, integrating their learning with real contexts and bringing their attention back to their cultural roots. Without this critical piece, we will continue to churn out colonised, individualistic minds sold out on modernity, which will be at cross-purposes with the larger vision.

As we imagine this larger ecosystem of initiatives as a forest, apart from the right conditions of moisture, temperature and nutrients, we realise that it needs two important things in order to thrive. One is a rich mycelial network through which information can be in a constant flow, informing every part about the whole. The second is a healthy and diverse population of agile pollinators who can network and foster collaboration. We need to expand the scope of community media like local newspapers dedicated to the revival of the bioregion, and invite more and more people to participate through the different platforms.

Though there are small groups of individuals studying the impact of the Government’s taxation policies on Auroville’s economy, the dependence of the community on external sources of funding, the order of investment by Auroville residents and as a collective in the global banking system, etc. their implications and alternative ways forward remain to be studied and understood more deeply. This involves individually and collectively diving into questions like ‘How much do I/we care about my/our money being invested in arms, toxic, chemicals, fossil fuels and other forms of violence? How do we build critical mass to push the system to cater to our needs as ethical investors? Are we willing to accept less financial returns if we knew that our money was not doing harm while being held by banks?

When it comes to human systems, every attempt at creating an imaginative, self-governing and self-managing one unleashes the inherent complexities of the human mind. Often, deep-seated fears, assumptions and insecurities get unleashed in the process of transitioning out of known and habituated frames like transaction, accumulating and using mainstream money, playing by the rules of the game already laid out, knowing one’s role in hierarchical structures, etc. To lead and hold this meta-exercise requires a mature and agile collective leadership, which is deeply committed to understanding the many dimensions of the crisis, to an integral practice involving all levels of the being (the physical, vital, mental and the spiritual), to developing the ability for self-reflection and to work in teams. Strengthening our ‘evolutionary leadership program’ for local change-makers will be at the core of this work, in order for it to grow deep roots, sustain and thrive over the long term, at all levels from the personal to the global

I would like to express my gratitude to Divyanshi Chugh, Gijs Spoor, Manish Jain, Manoj Pavitran and Suryamayi Aswini for their contributions towards shaping this article.

Bio:

Sangeetha has spent over two decades engaging in many social experiments exploring what it means to be an effective change agent in the face of today’s multiple converging crises. Her long search to integrate inner and outer change led her to Integral Yoga and Indic Knowledge, both of which she is a keen student of. She is one of the stewards of Vikalp Sangam, a pan-Indian confluence of systemic alternatives. She loves to sing, write, forage in the forests and design systems for change.

Notes:

Some institutions might be churning out very imaginative and creative people but to serve the capitalistic economy. The explosion of industrial creativity cannot be denied. The question is “what is the imagination serving?”

- Charles Eisenstein’s ‘Sacred Economics’ was a book that every one of us had already read and deeply resonated with. This made it easy for us all to quickly get onto a common shared space and take the next steps.

- https://incarnateword.in/

References

Henk Thomas and Manuel Thomas, Economics for People and Earth: The Auroville Case 1968-2008, Social Research Centre Auroville, India (2013)

Charles Eisenstein, Sacred Economics Banyan Tree (2015)

Olivier Hetzel, The Future of the Economy, A Holistic Socio-economic Paradigm for Evolving Societies, Dance with thy Life, Auroville (2007)