by Katie Wachsberger كيتي واكسبرجر קייטי וקסברגר

A few months ago someone from one of my social circles in Israel reacted to a message I shared regarding large-scale disregard for Palestinian civilian life in Gaza. He wrote, “Israel is not obligated to do everything in its power to protect the lives of Palestinian civilians. Rather, it is obligated to do everything possible to protect the lives of Israeli civilians, and soldiers, and thus the lives of Palestinians may sometimes be the price of that task.”

This made me wonder: For whom are we responsible? Whom are we morally obligated to protect and care for? And can protection and care really be achieved when they cost the safety or lives of other beings? We live in a world where we are constantly prioritizing the wellbeing of some over others. I wonder if our current moments of deep grief and darkness can teach us to reevaluate our thought patterns of identity, community, and belonging and to accept opportunities to learn what it really means to be human.

A Different Approach

For the first weeks of the ongoing violence in the Gaza strip I was hosted by Tamera, a research center for peace and intentional community in southern Portugal that supports activists from around the world and promotes ecological and social regenerative practices. Tamera puts a heavy emphasis on the principle of “free love,” referring to the removal of barriers that prevent us from channeling the energy of love beyond the framework of monogamous relationships. This unconventional approach is the bedrock of the community’s work with activism, justice, and peacebuilding, encouraging us to redefine our relationships with all beings and dynamics around us based on unfettered love, mutual responsibility, and care.

It is argued at Tamera that we cannot address underlying causes of violence or the inability to peacefully coexist among countries, or even groups of people, before we address the ways in which we interact on a much smaller, interpersonal scale in our lives and relationships. That we cannot imagine a peaceful society when love is so restricted and ingrained in dynamics of hierarchy, power, control, ownership, and the search for safety.

“This focus on challenging monogamous relationships,” explains Hala, a friend from Egypt who had visited Tamera before I did, “seemed strange and removed from the reality of our lives, especially in the MENA region. I don’t feel necessarily compelled to accept this way of life, but the concept underlying this philosophy is powerful; it makes us wonder if the act of preferential love is part of our higher nature or whether it is a weak spot in our culture that limits our ability to be united in action and sentiment.”

When I received the message from my acquaintance about the obligation to prioritize Israeli lives over those of Palestinians, it occurred to me that perhaps this idea of free love challenges our conceptions of safety and obligation. Tamera’s ongoing research about unrestricted love led me to examine assumptions that love can and must be hierarchical. While safety in relationships comes from having expectations met, mutual trust, and being truly seen, it is also rooted in the concept of prioritization: if I do not have the security of being prioritized — of always knowing that someone or something will put me above all else — how can I feel safe in this world? The way in which a citizen expects her state to prioritize her wellbeing over the lives of those across the border, no matter the price, mirrors her expectation that her partner will always prioritize her needs over those of others.

These expectations are rooted in the same illusion that our wellbeing and safety require hierarchical structures, and that we need to be more important than others to ensure that our needs can be met. This is based in a fear-oriented paradigm that assumes scarcity, as well as in the illusion that the fulfillment of our life’s needs relies on actions of others external to us — that we are not the drivers of our own experience. Our understanding of safety assumes that we can control the external, manipulate our surroundings so that we can anticipate and rely on things happening our preferred way, and build a reality that meets those expectations.

Letting Go

But in these moments of darkness when suddenly nothing makes sense, we have a learning opportunity of a lifetime to confront the truth, which is that we have no control, no escape from constant change. The only moments we can find safety are when we accept the ever-changing nature of our world, breathe into what is without averting our gaze, and accept that all we can do is try our best to bring safety and love to as many people as we realistically can.

These moments — happening as they are in the midst of much agony — are sacred teachers of how we can love each other: When we accept that safety and security cannot be engineered through commitments and expectations, that life is erratic and unexpected, we have an opportunity to imagine what it might be like if we choose to love with all our might in every moment that allows it. We are open to practicing truly uninhibited universal care for all human beings, as we know that any structures or agreements will eventually disintegrate . . . like almost everything else that exists on Earth.

And yet, in seeming contradiction, these critical moments also teach us that we have tangible needs that require us to rely on support from others (sometimes in a way that implies hierarchy or prioritization). We understand that focusing our care and love on some before others is a phenomenon embedded in our DNA as a mechanism for survival — but the revolution is in our ability to extrapolate from this natural function the tools to expand our hearts to love all beings unconditionally.

This past December, when the atrocities were piling up and the humanitarian situation in Gaza was starting to plummet, I was spending many sleepless nights trying to coordinate the movement of my friend’s family from Gaza City to a haven in the south. One morning I awoke to a message from my friend linking to an Al Jazeera news report displaying a photo of a family of about 25 men, women, and children, all waving white flags. The caption identified the family; they had my friend’s last name. They had been bombed on their way to the safe space in the south. All of them were killed.

My heart stopped; we had failed, and perhaps I was partly responsible for this unbearable tragedy.

A few minutes later, we discovered that my friend’s family was still in their home. They had not yet tried to leave and were still safe. Immediately I felt relief, but then I wondered Why does my friend’s family deserve to live more than this other family with many of the same characteristics and the exact same family name? If real love is universal, why should I feel any less disturbed by their death?

Acknowledging Some Biases

While I do believe that our hearts can expand infinitely with love for all beings, and that love for one is not inherently at the expense of love for another, it is unrealistic to expect humans not to feel closer to some people with whom we have deep connections, or share vision, experiences, values, stories, blood, traditions, language, let alone allocate valuable time and energy to some more than others.

We also make agreements with people to co-create projects, a home, community, new human beings — and those agreements allow for us a deeper capacity to give and to love others because we can share the responsibility of having needs met. Sometimes we need others to make important things happen -— like growing food to feed ourselves and those around us or providing shelter for other beings — and these efforts require organizing and prioritizing some connections over others in specific circumstances.

Similarly, it is important to acknowledge that states, like human beings, have limited resources. Such resources include time, capital, food, water, shelter, and energy, which physically cannot be distributed equally to all of the planet’s inhabitants. So we have decided as a society to organize the distribution of these resources in the same way we organize love and care: This reinforces nationalistic politics within states that are organized around ethnicity, religion, language, and factors beyond our universal humanity.

We should not be hard on ourselves for the natural, evolutionary characteristic of the human psyche that looks to extend a hand to those in our “in group.” But perhaps we should question the nature of prioritization as it exists in our world today, notice when it comes at the expense of the collective good, and when it inhibits our ability to expand our hearts fully. In these moments of learning, of extreme darkness and despair, we can see how these systems or providing care — while natural and well-meaning — have failed to truly protect us.

Expanding Our Idea of Responsibility

I sometimes think about my own family members working in the defense industry, and others who work in harmful and polluting industries that are creating an increasingly dangerous and precarious society for the next generations to navigate. The defense industry in Israel not only creates economic incentives for violence, but also allows trade with government entities that oppress democracy and human rights — not to mention financially marginalizes creative, educational, and regenerative industries within our national economy.

Yet so many people justify their involvement in destructive industries or actions with the argument that they are providing for their families and children. “We are creating a more robust, powerful, and safe society for our children,” argues my cousin.

Our Jewish Israeli children are perhaps the only children who will reap tangible security benefits from these industries, but ultimately they will live in a world where weapons are trained on neighboring populations to increase their accuracy and scalability, perpetuating our society’s reliance on military infrastructure and safety nets of violent actions and surveillance. If our own nuclear priorities come at the expense of the collective wellbeing in such profound ways, leaving us vulnerable to repercussive attacks and constantly leading us to play the role of perpetrators or violence, are we really looking out for our loved ones?

What if I were to be responsible for all children the way I am responsible for my own biological children; if I could acknowledge that their wellbeing is not just about the insular reality of their biological parents making sure they have what they need, but rather, about living surrounded by beings taking care of one another out of the wisdom of interconnectedness.

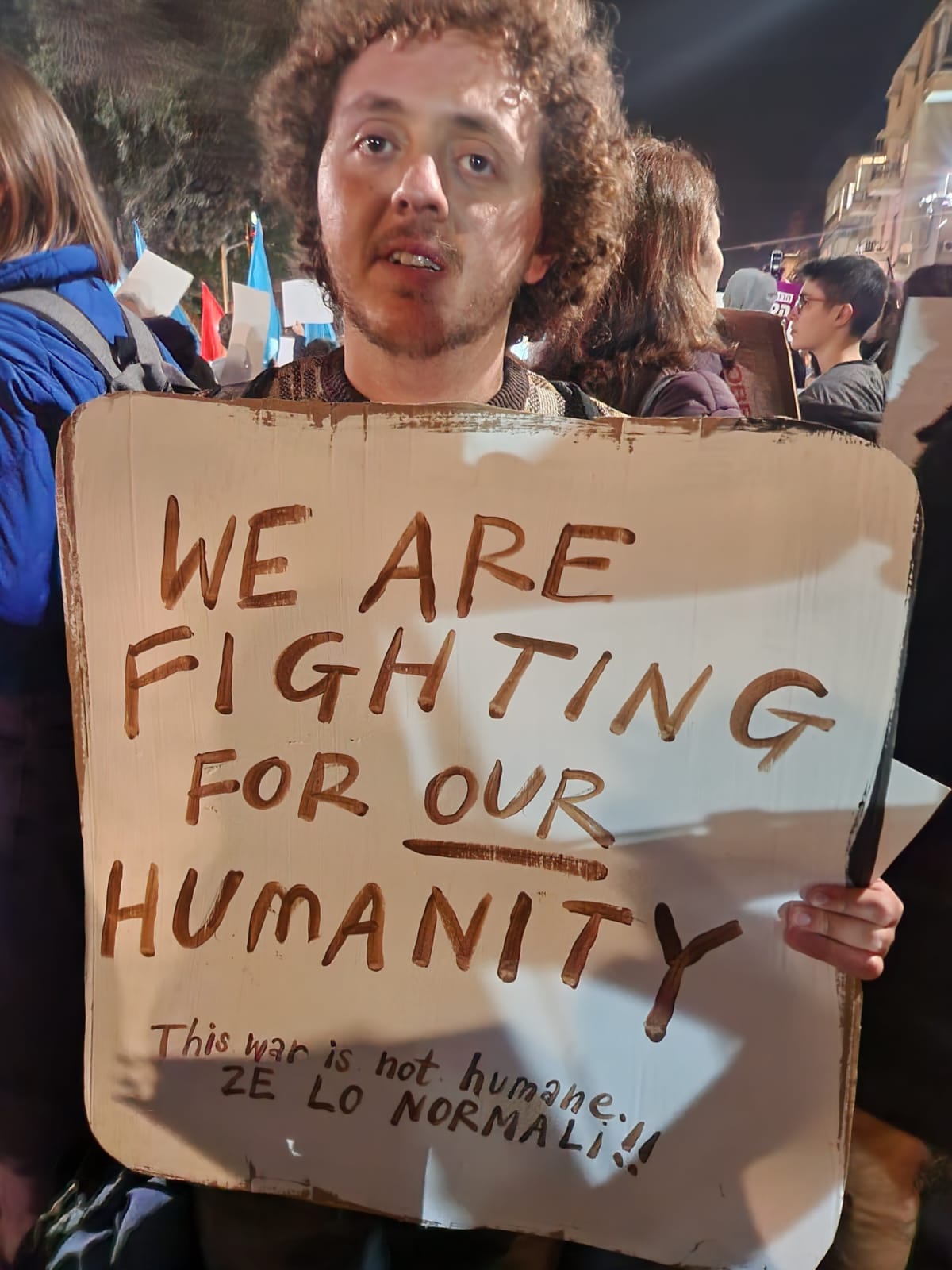

There will always be people in our lives to whom we give more, and there will always be relationships in which we invest more time, resources, and care. Over the months of the genocide, I have consistently decided to allocate time, efforts, and savings to groups within my society who share my values of nonviolence and strive for an equal and decolonized state structure, even though the real challenge for someone like me is to accept the humanity of those I disagree with and allocate time to attempting to engage in dialogue with them about shared humanity.

Amir, a fellow activist from the West Bank, has repeatedly tried to convince me to step out of my comfort and spend more time with those who do not agree with us regarding the vast imbalance of power in this ongoing occupation and the unprecedented violence against Palestinians. “Jewish Israelis should spend their time trying to sway parts of Israeli society that are too traumatized to understand that they are manifesting evil.” And while I agree on a practical level with his argument and believe that my emotional wellbeing is tied to that of all inhabitants of this land, I long to engage with efforts and communities that mirror my own values; that’s a much more comfortable place to be.

But the key to real love — love that starts from those near us and extends to all beings — is understanding that nobody is safe until we are all safe, and that our relationships with each other cannot bring us true light if they are there only to benefit those directly involved.

The people on one side of the border will never know peace and harmony if those on the other side are suffering. In the words of Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, “There is one precious thing I cannot ask God to just give to me and not to the rest of the world, and that is peace. Either it is for the whole world, or it isn’t there at all.”

May all beings know real peace.

Katie Wachsberger is an entrepreneur in the sustainability and agricultural sectors and an expert in the Gulf countries’ society and economy. Her background is in academia, research, venture capital, and post-capitalist organizational and financial structures, and she is currently focusing on the interrelationality of ecological and social justice in the regional context. She has spent years being active in different initiatives promoting justice for Palestinians. Listen to an interview of Katie on the topic of questioning Zionist upbringing.

Some recommended resources:

Seeds of Peace conflict resolution summer camp whose alumni (including Katie) are working in 27 countries worldwide.

Os Forum for Regional Thinking aims to “bring about a change in the way the Israeli public perceives the Middle East and Israel’s place within it, and to provoke complex discourse about the non-Jewish-focused region.”

DANA Global, which Katie cofounded, is an “Abu Dhabi-based venture builder and investment platform that supports women-led startups in desert technologies, including sectors of agritech, food tech, water solutions, and renewable energy.”

Katie is currently managing the association Union de los Rios in Andalucia, which aims to create enabling conditions for the emergence of a situated, complex, life-supporting natureculture.