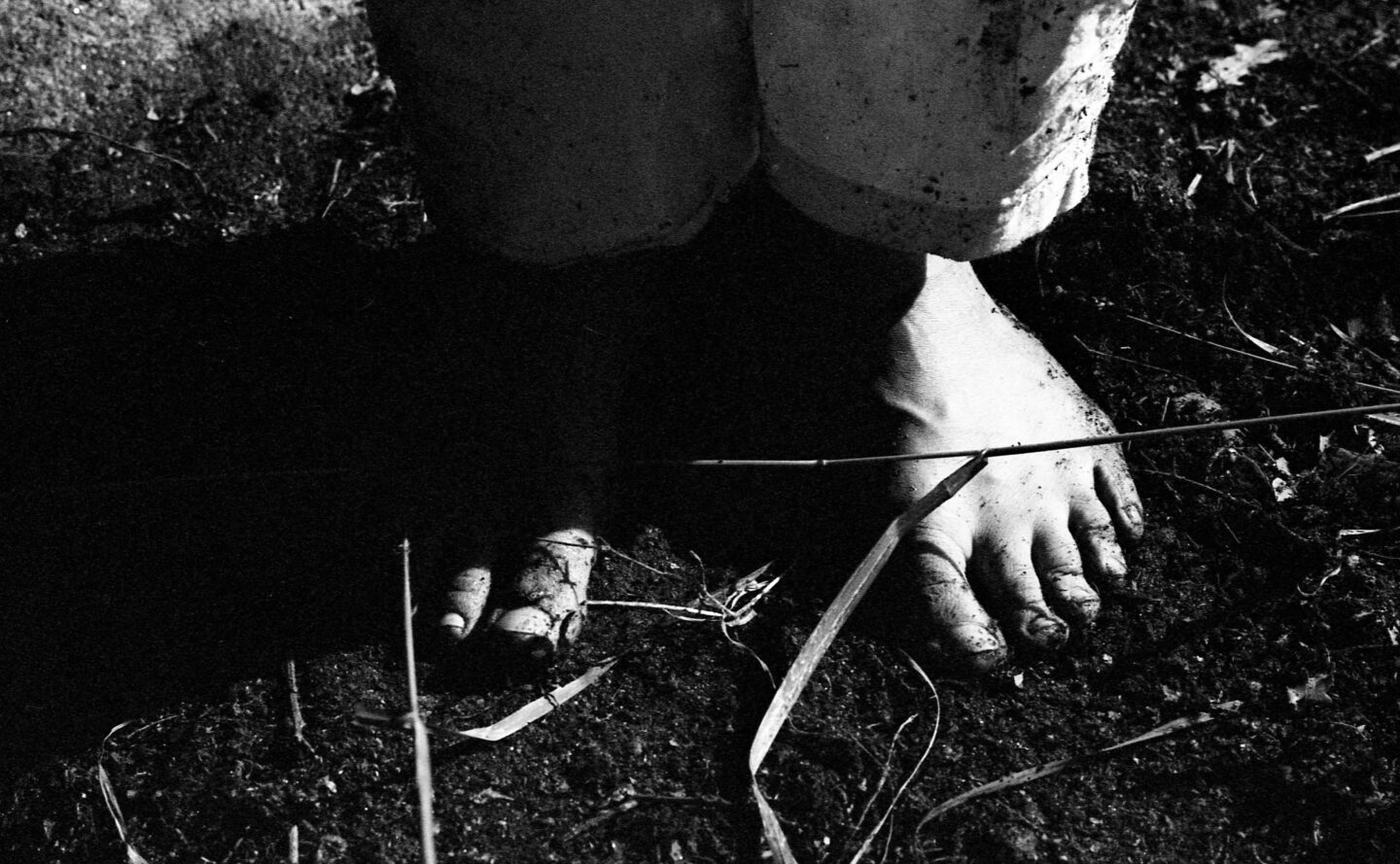

These texts by Dino Siwek and Mar Mordente are a continuation of a conversation that began in March 2024 with the Senti-Pensar Gaza gathering. This meeting took place in São Paulo, Brasil, and marked the start of an artistic-pedagogical inquiry into the culture of genocide. Photographs by Kya Roy Fay of performer Mar Mordente.

We found ourselves (and still find ourselves) confronted with a shared perplexity and astonishment: We remain incapable of interrupting massacres. And massacres continue to be produced. The names vary and are often contested: genocide, ethnic cleansing, self-defense, necessary evil. These debates matter. Taking a position is both important and urgent. But where do our voices resonate from? How can we learn to position ourselves from other frontiers — those at the edges of the Earth, from the intelligence that arises from cells, or from the words that emerge out of the shadows — frontiers that do not reiterate colonial logics of separation, domination, and extraction?

We are struck by policies of death in profoundly unequal ways, but collective pain cannot be processed in isolation. The enormity and diffuseness of what must be processed overwhelm us, so we orient ourselves through a set of questions that help us witness, digest, metabolize, feel, see, and simply be.

This is an invitation to enter a space for open dialogue, embodied and affective processing . . . for daring to bear witness, to face realities head-on, to resist forgetting, and to seek clarity in the fertile darkness of the Earth’s humus.

How can we unlearn the annihilationist impulses that continue to enable genocides?

How can we recognize that the impulse to annihilate also exists within us?

How can we move beyond identifying solely with what we perceive as good, just, and solidaristic?

How can we activate the body to feel beyond automatic responses, beyond the urge to quickly resolve the suffering, anger, sadness, indignation, and despair brought by the genocide?

How do we process these effects?

How does the Earth receive the dead?

What movements are necessary to hold and metabolize pain, shock, and trauma?

If we are extensions of the Earth-body, how do we co-responsibilize ourselves for this movement?

How do we perceive the Earth expressing itself through us? How do we attune to this listening?

Who speaks on behalf of the Earth?

Who has the right to speak on behalf of the Earth? Who names the Earth?

The two texts that follow in this series, in some way, have emerged from these questions. However, they do not attempt to answer them or even explore them through closely related paths. Instead, they reflect how walking together through this inquiry transforms each of us. They invite us to witness the pain caused by a bomb that not only shatters bodies but also splits the Earth, its impact contaminating the Jordan River, from the river to the sea.They challenge us not to articulate what we wish to say but to attempt to emit signals — pulses that might open possibilities for life beyond monocultures.

These signals, far from offering clear paths, are tentative — perhaps even desperate — attempts to persist. They are an effort to piece together some mosaic, some patchwork that might make a different future possible once again.

Ecos

by Dino Siwek

My daughter has been asking questions about death. Not just the death of people, but the death of the human species, other beings, and the planet as a whole. She also asks, curiously, what happens when everything ends. These aren’t questions surrounded by anxiety. In fact, there’s only curiosity, and some measure of tranquility. I wonder if what protects her is the innocence of a four-year-old child or if there’s something more. I wonder if the children born near the end of the world (or at least “a” world), are already configured differently to face collapse.

Lately her arrow of exploration has shifted direction. Instead of the end, she has turned her questions toward the beginning. What existed before everything? As a father, I feel obliged to both provide truthful answers to her questions and create space for the mystery to act within her. I feel it’s my duty to balance the things I can teach her with the delicate ability to not assume I know more than she does about everything. I constantly strive to make room within myself to accept that she might be better equipped to respond to certain situations and circumstances — without making it a burden for her, an abyssal child, but still a child.

When it comes to questions about the mysterious I avoid giving any overly definitive answers. At most, I try to clear her imagination of ready-made ideas so that the unknown can express itself through her.

Recently she became interested in knowing who created everything, and, faced with my uncertainty, she promptly said: “It was a man, Jesus.” I took a deep breath, parented myself first, then responded. “Nana, doesn’t the world seem too big to have been created by one man?” She agreed, thought for a little while, and then said: “I know! There was already land before the Earth, and it was generated from inside the Earth. And in that land, there were worms.”

The land within the land and Jesus take me to Palestine, to Israel, and to everything that land has been and wished (or not wished) to be. I come from Jewish parents, Jewish grandparents, Jewish great-grandparents, and beyond that, I know nothing more. The interruption of ancestry is a living characteristic of those who have suffered genocide. My daughter, however, does not have a Jewish mother. Within our small family nucleus, our daily lives, and our choices, her mother’s religion (or that of any of us really) is an absolutely irrelevant issue. The world, however, does not exist only in me. For Hitler, for example, my daughter would be Jewish. For Netanyahu and the other fundamentalists surrounding him, perhaps not.

To them, my lack of fundamentalism, my ignorance about the land they call Israel, would be enough to discredit my view of the current genocide carried out by Israel in Palestine, which they euphemistically call a war. Another term with which I might be described is “self-hating Jew.” In other words, my criticism of apartheid, 70 years of illegal occupation in the West Bank and Gaza, the destruction of all civilian infrastructure (including schools, hospitals, clinics, libraries, theatres, community centers, elder care facilities, and universities) in Gaza, the deliberate killing of civilians (more than 52,400 individuals killed and more than 118,000 injured as of May 1, 2025, the majority of whom are women and children, and the count grows daily); the continued policy of land theft in the West Bank; and the siege preventing aid from reaching Gazans, is seen as a symptom of a disease called self-hate, rather than a concern about displacement, death, and destruction carried out in my name.

But let’s return to the land within the land, whose name I will refrain from debating for a moment. It’s clear that within that space, not just different peoples but also different lands, different cities, and different stories share the same ground. This is not unique to there. I recall, for example, New Delhi in India, whose current city is the ninth version of Delhi, each with different peoples, power structures, and spiritual dimensions. What is different about the place we are discussing is that these various cities have collapsed not in space but in time.

In today’s Israel/Palestine, different temporalities have been forced to coexist, and the collapsed time of the present makes this a conflict in which pasts and futures are constantly brought to the surface. The land within the land does not inhabit the underground or distinct temporalities. Instead, all exist at the same time, though many people are able to see only the layer in which their own light, their own identity, their perfumed and distorted reflection shines.

These last two paragraphs might certainly sound like an “impartial” text. If so, it wouldn’t surprise me if they provoke feelings of disgust in bodies more attuned to the raw reality faced in Gaza and the West Bank.

Peeling Back Layers

I feel that one of the paradoxes we have to face in order to try to open space for different politics in the land is that the current conflict and its possible solutions are both simple and complex. It is simple in the sense that the violence, the bombs, the forced displacements, the apartheid . . . they all must stop. Before a solution, before an agreement, before any sort of preconditions are set forth. Yet, proposals for any long-term solution that embrace the rights of different peoples who hold long-established relations with that land to remain in that land, have been intentionally made unviable at present.

So, how do we make what is invisible viable again? I suspect part of it is to be able to open more space in our guts to deal with the complexity of the situation, which involves developing more capacity to sit with feelings such as disgust and rage at at least some degree (depending on your preconditioned mindset) of injustice, no matter what will be on the table. I cannot claim (and no one should) to be able to list and unpack all the different layers this multigenerational conflict demands, but I think it is necessary to talk about the trap into which Jews and Palestinians have been forcibly placed. Particularly, the often-invisible power structures responsible for creating and maintaining the permanent state of conflict experienced in that region for at least 70 years.

The foundation of the state of Israel is a junction of the decline of colonial administrative structures; the forced delegitimization of the Palestinian people, long inhabitants of that land; and the collective Western guilt for their tacit agreement to the Nazis’ genocide of the Jewish people. Because guilt over not stopping the Holocaust is a central factor in the failure of other nations to step in and put a stop to Israel’s violent authority. The narrative that Jewish people need to “defend” themselves at any cost in ways that were not possible in Nazi Germany remains one of the engines of the impunity experienced by the state of Israel in its discriminatory policies against Palestinian people. And here again a call is needed to examine the multiple lands, the multiple layers of complexity that need to be sustained if the world can honestly look at what is happening in that land.

Antisemitism is not an invention. Antisemitism is clearly on the rise worldwide. Part of this rise, though not all of it, comes from people very angry about the ongoing slaughter in Palestine, but struggling to separate Israel from Jewish people. This conflation of Israel with Jews is, on the one hand, strategic for those in power in Israel. It enables them to shut down any critique of Israel under the guise that it is a critique of Jews, or even a call for our annihilation. There is intentionality in reducing the experience of being Jewish to a requirement to be fully committed to the current state of Israel, even though Judaism existed and resisted without the state of Israel for almost 2,000 years. Furthermore, mislabeling critiques of Israel as antisemitism gives the impression that Jews are under existential threat, stoking fear and leading some to become more supportive of extreme measures in the name of protecting “Jewish safety.”

It’s essential to understand, then, which narrative is being amplified when we mobilize anger and fear from this mixture. There’s the narrative in which the safety of all Jews in the world (regardless of the seriousness of the threat) outweighs and justifies the genocide being waged on Palestinians. If it’s true that having been victims of genocide in the past, with the potential for repetition imagined around every future corner, is at least i part how Israel justifies its policies of extermination, occupation, and racism in the West Bank and Gaza, this rationale is also slowly undermining Israel’s own existence.

The horrific scenes of Hamas’s violence on October 7th are constantly mobilized because Israel’s existence as it is today fully depends on triggering a response to trauma. For that to work specially for the non-Jewish supporters of Israel, however, the memory of the prior genocide suffered needs to be greater and more impactful than that currently being waged by Israel.

Here lies yet another paradox to be faced by Jews who identify with, defend, and believe that Israel is their source of safety and peace no matter wherever they are in the world. The violence with which they think they are protecting themselves is the same violence that weakens and makes Israel unviable. It is not surprising that, for example, more and more young people from the United States (which is, in the end, where the safety of Israel really lies), who have less of the memory of Nazi Germany and more of apartheid Israel, are becoming more critical of Israel, and the Palestinian flag has become a global symbol of liberation and anti-oppression struggles.

It’s also necessary to recognize who else the narrative of “defense at all cost in order to avoid another holocaust” serves. By opposing Hamas, U.S. ideology also expresses its dominance over the rest of the world, through Israel. This feeds the collective myths surrounding the brave frontierspeople of the West invading the East, and of the individualist neoliberal Christian fundamentalism that destroys the possibilities of collective struggles, whether political, social, or environmental.

Rights, Wrongs, and the More-than-Human

Let’s zoom out of global politics, though, and get back to the politics of the land. That land within the land. That land promised to so many people. That land over which no one ever asked: But what about those Palestinian people there? That land that is so physically distant from myself. I write this text from the far west of the country today known as Canada. It’s 10,848.05 kilometers away from Jerusalem. I was born, spent most of my life, and have my permanent residence in São Paulo, Brazil, exactly 10,552.63 kilometers from Gaza City. I’ve never been there, nor do I intend to go in its current configuration. Still, there is a piece of land waiting for me there, over which I officially have more “rights” than people who have been there longer than the millennia-old olive trees. Olive trees that have survived everything, except the brutal Israeli bulldozers.

We do need to question ownership of the land, whether in Israel or anywhere; indeed, whether we humans can claim any ownership of land. And while the massive humanitarian crisis experienced by Palestinians needs to be addressed first as it has been here so far, we also need to open space to talk about the violence the land is having to bear, and the sort of destruction that is also being imposed on the non-human realm. If that is a sacred place, the sacrosanctity of it cannot be reserved only for people — even worse, for certain people who think for whatever reason they deserve more.

It is true that claiming ownership of land is deeply problematic, especially when it reflects a logic of control and exclusion. At the same time, the idea of ownership has been used so aggressively and for so long to justify violence that even those of us who reject it are caught in its web. We don’t get to opt out of the conversation — because the logic of entitlement has already been used to define who belongs and who doesn’t.

In that context, those of us who might technically have “rights” to land we’ve never touched, while others who have lived there for generations are denied that same right, can choose to use our position differently. Not to reinforce entitlement but to interrupt it. Even if it feels uncomfortable or risky we can use the rights granted to us by unjust systems to expose their injustice and to support the return of stewardship to those who have been caring for the land all along.

It goes without saying, I think, that if we have rights, moral or not, claimed or not, we also have responsibilities. We are responsible for the things done in our name, including the complicity in the slaughter of Palestinians that has been ongoing for seven decades. I think it is important that when we speak, act, and take position, we do so carrying the weight of complicity and responsibility for these deaths on our backs. Not in my name? That choice hasn’t been ours for a long time.

Responsibility, though, is something that connects us not just to the harm we inherit but to the possibilities for repair and renewal. Complicity, then, is not a static burden but a thread running through us, binding us to others. It is not a condemnation but a call to action: an invitation to participate in the ongoing work of reweaving a thorned tapestry into something else, yet to be made, yet to be any sort of safety for those that dwell and relate to that land, including the land itself. The land within the land is not just a metaphor for historical layers but also for relational ones. The past does not sit idly behind us; it is woven into the present, shaping how we see (or don’t), how we act (or don’t), and how we care (or don’t).

To look at complicity not as guilt but as relational accountability is to recognize our responsibility to reweave the patterns of harm into something that nourishes life instead of depleting it. But we need to stop depleting it.

By telling in this text a story of a child and the mystery that lives within her, I apologize and stand in solidarity with all those who have unjustifiably lost their children in Palestine, and with all of us who are terrified of being alive, and therefore complicit, in a world that deliberately kills children.

The War Never Learned to Dream.

That is why, before sleep, I refuse to feel its threat.

by Mar Mordente

Since October 2023 (and long before that), I have closed my eyes in tears and descended into the darkness at the Earth’s core. And it is from this frontier that I speak now. I breathe death and feel the Earth, a seismic movement rising from within the cells.

I search for words shaped like dreams that emerge from the shadows. I wish to rupture the genealogies of genocides, as one dreams with the loving force of ancestral time. I try to listen for a future: voices that sniff out the present, diluted across multitudes of times and beings.I long to speak a language that intertwines at the edges of unknowing, avoiding the false dichotomies of certainty and despairing moralism.

When everything around us is opposition and hierarchy, cycles of violence emerge from other cycles of violence, feeding the logic of threats and vengeance — even if only in careless words posted online.

The hollow of hatred knows how to find shelter in the deepest and most banal corners of our psyches…

I will not dwell on the news and information churned out by the machines of war, although I know the deep necessity of questioning the discursive, imaginary, and material fictions of power to speak about (dis)solutions for the Palestinian genocide:

Israel — war-industry; State — alliance-on-extractivist-route; State — ascension-of-the-Messianic-right; State — modern-colonial-project; State — apartheid; Israel — white-resolution: instrumentalization-of-antisemitism; tragic-chapter-of-the-catastrophic-history-of-nation-states…

There are many Israels, millions of Palestines. And countless Brasils, too — one of which I write from in this moment. The nation-state thrives on a false foundation of unity: universalisms that seize our words and actions into the domain of the fruitless, the impossible, the lament, the end of worlds, or the end of the other.

For this reason, now, even while physically distant from the Palestinian genocide, I feel its proximity in the wounds of the soil where I live. Eco-genocides cross this land, and their reverberations urge me to listen more radically to the murmurs of the Earth. These subterranean impulses push me to create spaces for collective mourning and metabolization — a mourning that does not bow to hierarchies of identity or species. I want to be kin to all that is alive, embracing the inviolability of its seed, its sap, its vitality.

I insist on learning to exist at the borders between dream and death, at the edges of the Earth’s humus. Only there have I found some space to try and remain with the pain of the other for more than 10 seconds of a story. To expand the time of a feed into 10,000,000,000 seconds. To create space-time within my own throat, turning with the Earth’s rotation to say:

I’m sorry. I feel so much. I feel everything that cannot fit into mourning.

And still, to feel useless.

And still, and yet, to persist.

How can we tend to the wounds bleeding inside each of us who lives through or witnesses the destruction caused by these gravely mortal times?

What if, instead of looking outward, we took up the work of repair, listening as one who auscultates the expansion of consciousness over time?

What if we refused to be right and instead moved toward vibration — to resonate with the many voices calling from liver and heart to the cease of all fires?

How can we stand before the unequal abysses of violence without seeking a place of identification?

What courage do we lack to ask about justice as those who refuse to dream of themselves?

The war never learned to dream. That is why, before sleep, I refuse to feel its threat.

Words can be honey and/or poison. In times of ruins and mourning I prefer to speak through the porosity of dreams that sprout from the Earth. Dreams that take me far, into the dark of the night, toward vast expanses. Dreams for unlearning the culture of genocide.

I share three dreams with you, in temporalities that help me listen to the invisible and ask:

1) I dreamed of the war before the genocide began. Or is it because we live in times of abysmal disenchantment?

2) Those who hide behind the dead or deny the mourning of others lose access to ancestral knowledge. How can we live through collective mourning?

3) As Mohamed Amer said during the pro-Palestinian rights march organized by Jewish Voices for Peace: “We could be love and compassion.” He was speaking of (im)possible alliances between Jews and Arabs — “could be love and compassion” — and, interrogating extractivist industries, war, and colonial structures, he said: “One day, you will be charged for what you did to this land.”

DREAM 1:

A low-lying river landscape in the Middle East. Vegetation covered the waters, and there was a sandy path. A being — a creature, a woman (?) — guided the way along this trail. A profound love spread through space. (It was love, trust, strength, fury.) The path led to an old house, a secret meeting of many people from different places and origins. A plan was being drawn, and we were part of it. Then a gravely mortal war began. We found ourselves forced to spread across the battlefield. While we fought and tried to escape, a mysterious being, dressed in a cape and a hat, told us: “To overcome terror, you must walk at the border of life and death, which is different from the border of war. For war has never learned to dream.”

DREAM 2:

Again, the same old house. I was with some friends, playing and dancing in a gentle trance. Suddenly a dense atmosphere filled the space. I looked around: Thousands of dead entered the living room. Again, war’s destruction invaded the landscape. Those who had passed did not know where to go. We despaired, not knowing what to do, but we understood that it was necessary to cook for these souls. To feed the dead so they could break free from repetition (of pain and disenchantment) and find a path that nurtures wisdom in the face of fear, shock, and hatred. It was necessary to honor their lives, understanding mourning as memory and a path, not as imprisonment in the past. I repeated everywhere: “Not in my name.” I called out for the trauma not to be weaponized for profit and revenge.

DREAM 3:

A refugee camp. A war zone. Everyone desperately tried to leave, but a debt had to be paid. We lacked the currency needed for payment because, in the face of destruction, the values changed. A being of indescribable beauty approached. They carried a briefcase containing all the currencies of every country. But the debt was unpayable, because it was not national. The debt was with the mothers, with the Earth.

The texts that have just been shared were created through a series of exchanges between Mar Mordente and Dino Siwek, continuing the collective research project Unlearning Genocide.

Dino Siwek (he/him)

Anthropologist, educator, and researcher, Dino works at the intersection of climate emergency and historical and systemic violence. As a cofounder of the Terra Adentro project and a member of the Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures collective, he engages in pedagogical practices aimed at fostering ways of living that help us confront, rather than deny, our entanglements and complicity in harm to humans and non-humans, as well as the planet’s limits.

Mar Mordente (they/them) @mar_mordente

Born in Rio de Janeiro (Brasil), they work at the intersections of performance, radical pedagogies, and collective healing practices. As a diasporic person from familiar lineages of political exile (Argentine dictatorship and Jewish holocaust), Mar’s art-life research is guided by the concerns of decolonial struggles, specifically by the knowledges and experiences with and next to Indigenous feminisms and ecotransfeminists movements. In recent years their art-life work has been rooted in non-Western perspectives on dreams and collective rituals of healing and justice. Since 2023 they have been exploring practices of collective mourning based on dissident experiences and ancestral technologies. Mar co-directs the play A Bird Is Not a Stone, which tells the story of the Freedom Theatre, a project of art and resistance based in Jenin, Palestine.