By Kejal Savla, Arnaz Khan and Abhishek Thakore

Sarva-Anumati is a compound word: Sarva means all and Anumati means permission or consent. Hence, the term Sarva-Anumati implies the permission or consent of all. Introduced by Mahatma Gandhi, the concept of Sarva-Anumati was further championed by Acharya (Sanskrit for teacher) Vinoba Bhave who is also known as the spiritual successor of Gandhi. He was one of India’s most poignant social reformers and best known for his Bhoodan (Land-Gift) Movement. His life’s work is based on the principle of ahimsa (non-violence) and swaraj (self-harmony). Vinoba Bhave is responsible for laying the roots of deep democracy in India through his work in his ashram Brahma Vidya Mandir. Following in his footsteps, a tribal village, Mendha Lekha in Gadchiroli adopted deep democracy as their way of life. The village decisions are taken by full consensus from all the village members.

An urban youth movement adopting Sarva-Anumati

Decades down the line, we at the Blue Ribbon Movement got intrigued by Mendha Lekha’s self-governing efforts and aimed to inculcate that in the Movement’s processes. We reached out to Mendha Lekha’s Sahyogi Mitra Mohan Hirabai Hiralal. After understanding the interconnected web of systems through multiple dialogues, we consented to using Sarva-Anumati as our base operating system.

The need for this was prompted by several factors: wanting to build ownership in a volunteer-led Movement, a belief that sharing of power was the way forward for the world, and an intent to deepen the journey to a collective WE. While BRM was functioning quite smoothly the way it was, this seemed to be the next logical step arrived at after deliberation.

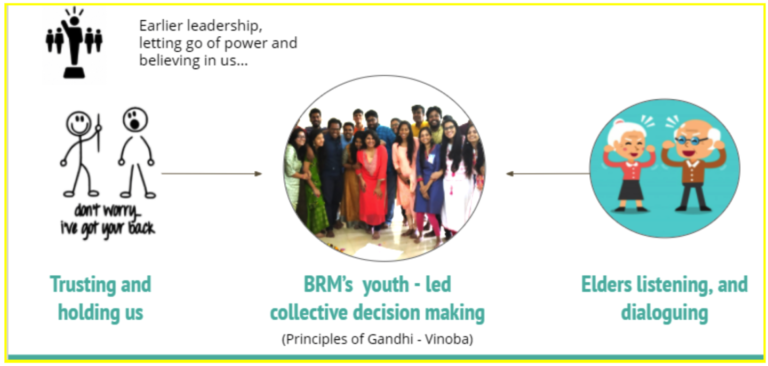

We moved from a one leader model to a collective leadership model, engaging alumni of the youth program to deep dive into social change as a lifelong journey beyond programmatic interventions. The youth alumni are voluntarily running the Blue Ribbon Movement as co-owners. Their volunteer effort and time fuel different functions of the Movement. They focus on understanding issues from a systemic lens and responding through creative ways via the different social initiatives. To make it easier to follow the process of Sarva-Anumati, a system was put in place to organise the different levels of participation by the members of the Movement.

We are the only urban youth Movement in India, to the best of our knowledge, who is practising Sarva-Anumati from October 2018. It is a very different context than Brahma Vidya Mandir and Mendha Lekha. Brahma Vidya Mandir is housed by women cohabiting the ashram, living simplistic lives. These women come together every day to discuss Vinoba and how to imbibe his life’s teaching into daily practice. They experience time without major constraints on spending it dedicatedly towards adhyayan (study) and shram (physical labour).

Mendha Lekha, a tribal village, is similar when it comes to the geographical coherence of the members. They are the residents of the village. The members get to meet and deliberate on issues that impact their daily lives. They have been the first village to procure community forest rights. They have worked towards self-governance by working through various issues plaguing them, be it alcohol addiction, women disempowerment, lands and forest rights, clashes with the local authorities and so on.

On the other hand, at BRM, the members are scattered all over the city. There are no geographical boundaries of our work and the nature of our work also doesn’t cater to our immediate daily needs. Being a volunteer-led Movement, we experience a shortage of time where the limited volunteering hours are divided into action, reflection, adhyayan, proposal drafting, and reaching Sarva-Anumati.

There is an important distinction between Sarva-Anumati (Consent/Permission of all) and Sarva Sahmati (Consensus of all). Given the context, Brahma Vidya Mandir and Mendha Lekha both practise Sarva Sahmati. This implies that no decision will move forward unless the last member of the group has given full consensus to it. If even one person objects to a proposed decision, it will be taken back to the adhyayan mandal (study circle) where it would be discussed and revised. Sarva-Anumati is the unique tweak adopted at BRM given our limited face-time together. The members are given the option of permitting the group to move forward with a proposed decision even if they are not in full agreement of it. This allows for time efficiency while also ensuring that each member’s concerns are heard and considered.

We found the deepest anchor to hold us is the curiosity of learning and commitment to walk together. It seemed a lot, but we had nothing to lose except the possibility of birthing something new!

“Sarv-Anumati (SAN) as a concept was very novel to me especially because I’d been into many activities in college and outside. Through BRM’s civic fellowship, I was trying to get to know SAN on a surface level but when my journey with BRM started as an alumni, the idea became a bit more familiar. The discussion that stayed with me was the one that happened at our retreat wherein even though I didn’t know much, my ideas, thoughts and opinions were asked and talked about. I’ve always been a bit vocal about having a say but SAN made me realize that how you should do it in a way that it’s taken by others also in a positive light. And the working system everywhere in my life was based more or less on hierarchy. The Sarv-Anumati (SAN) system actually gave a space for everyone to talk about their ideas and thoughts. It also gave me an understanding of how I could incorporate the learnings of SAN into my personal and professional life outside BRM. After getting to know the SAN system better, I started to use it in my life for instance, even if there’s a very small decision to be made at home or at the workplace, I tend to listen or ask for everyone’s opinion in the place making the process a bit more interactive and engaging. In college associations, I took initiative to provide that space to both myself and others as much as possible. Even when we’d attended a workshop by Point of View on media, in the group activity, I tried to incorporate the idea or core that SAN holds,” shares Lokeshwari who was a new member to BRM when Sarv-Anumati was introduced.

Why is this needed for creating a better world? What challenges and crises are we trying to respond to?

Through our collective adhyayan (study), we realised that the world crises are systemic and multi-layered.

Violence is built into many of our world systems. To take Democracy as an example, it operates on the principle of Majority vs Minority. This marginalises the minority and the system misses out on the wisdom that the smaller numbers would be possessing. This in turn creates a pressure on this marginalised group to accept and live with the decisions suiting the majority group. It further turns violent when these decisions are directly impacting the day-to-day lives of the minority group.

Hoarding of Power is another contributor to the existing violence. The power hoarded at the level of decision-making trumps all. The hierarchical decision-making processes prevalent today ensure the disempowerment of marginalized communities. Decision-making requires knowledge. And the hierarchy also controls the knowledge making and distribution process.

This leads to a Disconnect; among decision-makers, stakeholders, and the ones affected by those decisions.

These inherently violent systems in place call for radical shifts. Deep Democracy is one such experiment that strives to tackle the violence at the systemic level rather than offer band-aid solutions. It aims to facilitate Redistribution of Power among all the members of a society by empowering them to be part of the knowledge-making as well as influencing decisions.

We see Sarva-Anumati as a thoughtful response to current times. At the root of our inter-related crisis is the unequal distribution of power. This becomes the cause of oppression of minorities, disconnection from on-ground realities and centralization. As an antidote to this, a group agrees to make decisions only with full consent.

When a group does this, there are several consequences that naturally unfold:

– The minority is empowered to the highest extent possible. Even one person can object and invite the collective to pause and re-examine its course of action. In this way, a radical empowerment of every person reduces the barriers that exist in expressing dissent and differing views. Rather than someone else taking token measures to appease the minority, a decision taken with consent puts the ‘ball in the court’ of the person experiencing the oppression. Rather than programmatic changes, this process alters the very fabric of the decision making of a collective. Our volunteer, Pankhuri illustrates this with her experience, “An interesting incident was, the opportunities proposal that we were discussing to figure out how to share opportunities and rewards amongst the members of the Movement. As a newbie who had just entered the Movement at that time, there wasn’t any point listening to my views, yet I was encouraged and heard by other members. Now when I look back, I understand the importance of it. If I wasn’t heard back then, and had kept my concerns about the proposal to myself, it would’ve been an unstable decision for me later.”

– There is a feeling of one-ness and solidarity in any collective. Since every step is taken with the consent of everyone concerned, each person has to be patient to listen to the views of everyone else. It is this churning that eventually brings forth proposals that can be actioned. Such a journey taken together builds strong bonds and an ownership of the decision taken. When this happens, the implementation of the decision and the execution of its mandate takes much less energy than conventional ways.

“My first experience that I remember was in the retreat when Abhishek, our co-founder was explaining SAN. What is it and how does it work? At first it all went over my head, but slowly as it got into practice of the daily proposal and events of the BRM circle I got a clear picture of what it is like to practice SAN. It took me really very long to accept that everybody agrees to one thing and if there is a concern it will be solved. SAN has impacted my personal life too. Due to the practice in the group , it has made me patient, calm, accepting and my thinking ability has grown. I had never experienced it anywhere else besides BRM. I learnt how important it is to agree on one proposal or issue and then move forward by taking others together and not alone. Even the way SAN practice for new people was designed made me realise it takes time to inculcate the process of SAN, it’s a slow process which I learnt during the session done for the Yatra Group. Overall it’s a tolerance-driven process where I had to learn to grow slowly and patiently without jumping to conclusions,” shares Renita.

Pankati shares her journey of reclaiming her power. “Once we were discussing a proposal about the engagement and responsibilities of different anchors who represent BRM at partner organisations. I co-anchor the Partnerships vertical. (A vertical is a unit/team within the Movement responsible for certain domains). I used to feel that since I am new, how can I know what should be done? Let Kejal (the other anchor of the vertical) decide. Once, she asked me, what if you are alone? What will be your proposal? I was taken aback, how will I know what is to be done? I felt pressured and nervous to think and share. But later when I pushed myself and shared my thoughts on the proposal, I felt responsible to take action on it. Because now, I was a part of deciding and thinking what can be done. I had given my inputs rather than sitting and listening to everyone. The ownership increased towards the proposal and I felt confident to share my thoughts next time in any other discussion. Being a part of the Sarv-Anumati process, I have become more confident, patient and responsible for my words and actions.”

– The process of knowledge creation finds its right place. Neither can the intellectuals dominate the decision making, nor are they sidelined. Since the general assembly doesn’t convene on any matter beyond a fixed time, one cannot expound indefinitely. This space is made available in the study circles though where there are no limits in sharing and reflection. The study circles can be populated by those having the knowledge about the issue and use it in the service of the whole. Hence, the people with knowledge are able to be of use without being the dominating force or being ignored as the case could be. Asana expresses, “The core essence of SAN is that each person involved holds a grain of truth and they should have the space to be able to share their views.”

– As a spiritual practice, Sarva-Anumati requires us to see the divine in each person. When one is engaged in dialogue and the intent is to hear the deeper collective, a spiritual journey of cultivating listening, patience and connection with the other has started. This means we are willing to give up our power and privilege in service of the whole, so that the collective can thrive. The crisis of disconnection can get resolved in a deep way through this approach.

– Alumni Bindiya shares, “I saw SAN as tedious to begin with, but then it started getting enticing — how to see power, where to push, how much to push, how to own your own voice and encourage/hold space for those who don’t speak as much to own theirs. After this, somehow the other systems seem oppressive, and un-inclusive. While having the need to move far and move fast, as in capitalistic notions of the world, other systems do have their place, but no one seems to be stopping/pausing and reassessing. Another part that stands out for me is that the system (SAN) fails if people don’t own their responsibility into the decision making. ‘No objections’ is a pretty powerful way of communication and I’m wondering how to hold this further, and how much deeper one could go with it.”

By creating systems that are based on the wishes of the people, Sarva-Anumati helps shape a world that everyone wants rather than one that only a few people desire.

Arnaz elaborates on her entire journey with the Sarva-Anumati experiment, “Sarva-Anumati was introduced to us in parts initially when Mohan Hirabai Hiralal had come to Mumbai and did initial circles with us in Deep Democracy. And then at the retreat we spent three days understanding the interconnected web of systems and how Sarva-Anumati is a worthwhile experiment to try. In fact, we took the decision to adopt Sarva-Anumati with Sarva-Anumati, despite not having fully understood it. We went in with trust.

The next 6 months we started from scratch. Right from defining the group (from L1-L2 group to the tier system to OPEN) to setting up norms.. Expectations.. Adhyayans.. Drafting proposals..

We really could evaluate everything from square one. What does participation mean, what does inclusion mean, what are the entry gates of the Movement, what kind of people do we want, what about speed of processes and decision-making?

We discussed the pros and cons of the process. One of them clearly was that it is SLOW. Because agar sabko saath lekar chalna hai toh gati kam hogi hi (if we want to walk together, it is going to be slow).

And that’s also about our commitment as a collective and what matters to us.

Sarva-Anumati also corresponds with the core values of BRM. Some of them being Love, Non-violence, Trust, Authenticity, Togetherness, Integrity and so on. And we said we’re in for the long journey. Aur usmein matter karta hai not just WHAT we do but also HOW we do it.

Here, there is the difference of Sarva Sehmati and Sarv-Anumati. Given our unique context of city challenges, the group not staying together, plus the need to respond and act is higher than Mendha Lekha’s original pure Sarva Sahmati model, we also have our own unique version of Sarva-Anumati that works for us.

And at the last retreat we also spent a lot of time coming to the conclusion of making Sarva-Anumati our base process. Which means it becomes the operating system of our Movement. Ab humein agar yeh change karna hai, uske liye bhi Sarva-Anumati lagegi (Now to change this too, we would require Sarva-Anumati). No one person would be able to take any decision on behalf of the Movement without everyone’s consent.

And what it means for me is that I’ve been 100% convinced of this process since day one. It has also begun to seep into my inner spiritual journey. Because Sarva-Anumati distributes power equally to everyone in the circle, it is also important for each member to OWN their power. So then it’s even necessary for each member to have Sarva-Anumati within their own minds (the multiple voices) to come to consensus. To have a voice.

So, this is a slice about my Sarva-Anumati Journey.”

Sarva-Anumati as an educational tool

The stark contrast between university education and Sarva-Anumati lies in how knowledge is treated. The production of knowledge in a traditional university system tends to be done by experts, far removed from the ground. They are vested authority by the system and may not be questioned. The knowledge belongs to the University who charges money to dish it out.

On the other hand when it comes to Sarva-Anumati, knowledge production is a communal activity. Here, knowledge is co-created and belongs to everyone. It is a product of the collective, local and contextual churning of the people involved. In sharing knowledge this way, the collective also experiences the ‘leadership of the collective’ escaping from one person dominating the discourse.

Sarva-Anumati can act as a powerful approach for learners. Some aspects of it that we have applied in the past successfully include inviting the learners to completely design the syllabus from scratch. One of the future applications will be to have a Sarva-Anumati on the content that will be learnt as well.

The key insight to remember is that we are not ‘building agreement’, we are checking for ‘objections’. It aims to bring out the bare minimum we all can give permission to go ahead with even if we may not fully agree. One may not be fully happy with the decision but would ‘allow’ it to be implemented which brings a sense of satisfaction.

For eg: Person A says plans for an important group meet at 8am. Person B and C agree while Person D says no.

After discussion they find out no other time slot works for Person D and the decision has to be implemented by end of the day. They come to a consensual decision to share the agenda beforehand to receive inputs and send the proposal over text for Person D to consent by afternoon and implement by evening.

If any student has an objection to the content that is proposed, it is discussed and then decided on. Such radical participation in the creation of syllabi not only lets individuals’ take control but also lets a group go ahead and design learning that resonates with every member.

Similarly, what actions are needed to put the ideas into action can also be collectively agreed on. When such an agreement is done after adequate discussion, the force required to enforce such actions is minimized.

When one has engaged in the process of discussion, knowledge creation and consented to a decision, it creates their ownership and buy-in of the decision. This makes it a non-violent approach minimizing force on an individual to act on the decision.

The way to implement Sarva-Anumati as a pedagogy would be in these steps:

- Declaring formally that decisions going forward will be taken with full consent. Obtaining full consent first on this proposal itself. Identifying who all are in and out for the journey. This first step is most crucial and can often involve debating the pros and cons of such a system. The facilitator has to lay out the entire approach.

- Sharing differences between the general assembly and the study circles i.e. the role of study circles in generating proposals and the general assembly in accepting the proposals. Alongside this, interested members are invited into study circles to set up the basic constitution of the collective as well as what its norms will be.

- Teaching basic sign language that allows better communication to flow between people during a discussion

- Raising hand to make new points

- Double finger sign for clarifications

- Triangle for a process check

- “C” made with fingers for a clarification

- Crossing hands for a block

A moderator or facilitator can take stock of these or other interventions and allow the conversation to fully flow

Use of Language: Framing Proposals, Asking for Objections, Concerns and Giving pre-decided time/space to raise. Silence = Consent

- Bringing the crucial aspects of learning including the syllabus, the pedagogy, the course plan and the instructors for discussion on the table and creating proposals on each of these for discussion and passing. The discussions continue until the entire course outline is passed in the form of a proposal.

- Agreeing on the monitoring roles and the process of revisiting the constitution, norms and syllabus for any changes from time-to-time. The wisdom keepers of the community are in charge of ensuring that this happens

Such a collective that is based on Sarva-Anumati for its learning will be internally motivated to learn and truly enjoy the joy of collective learning.

Applying Sarva-Anumati in daily life

Sarva-Anumati is a practice that has an application in daily life too.

Starting with the intrapersonal level, one can engage with the ‘republic of selves’ that a person is. There are different parts of us with different voices and concerns. The internal process of Sarva-Anumati would be to facilitate a dialogue between all these parts towards realising a congruent direction. If any part of your psyche objects, it needs attention to resolve. The way of moving forward then becomes proposals for action that you check in with your mind and body for permission.

Often, disagreements manifest as discomforts and knots in the body. Energetically they feel like blockages for individuals. As a group also, one can sense into the energy and tell if it’s flowing or blocked at the group level. The churning has energy moving in its ebbs and flows. When we reach a place of full consent, it is not only in word but also in spirit. At such a time, there is an energetic release, a collective sigh followed by a flow of energy in the group for having reached the same place together. It is almost as if what wants to be born has manifested to one degree.

Doing this builds greater congruence and coherence in the way an individual lives their life.

At the interpersonal level, relationships can actively engage in study circles looking at their dynamics and generating fresh knowledge required for action. They can co-sense and make meaning in the presence of a world that is experiencing a crisis of meanings. This collective sense-making can become a basis for action. When a relationship takes actions only on full consent, there is a willingness to walk together and the violence and force of the relationship is reduced.

This methodology has applications in groups of friends, individuals living in the same housing complex, families as well as community groups. At each of these places the use of this methodology will reduce the amount of force required, increase ownership and allow for successful implementation of actions and changes.

Transitioning from an NGO to a Movement

The structure of an NGO with employees creates an employee focused strategy for change and is always dependent on money as a fuel. Many times, one gets stuck on a pre-set agenda, programmatic approach and creates a hierarchical structure of operation to prove numbers and instant change.

While NGOs have a role to play, we felt we would like to focus on creating something that attempts to respond to these challenges and focuses on long term systemic change, easing on the pressure of time and money with enough space to experiment and patience. Hence came the idea of a movement that is driven by people’s own motivation by volunteering time, energy and supported by small contributions by the community.

This change for us shows up in the way we organize our internal structure which encourages commoning of knowledge and power of decision making. We built this with the alumni of our programs to engage in an ongoing longer term journey of social change. Now as members of the movement they choose an area of their interest and volunteeringly lead those initiatives. We only have one part-time employee and the overall costs of the movement are citizen funded.

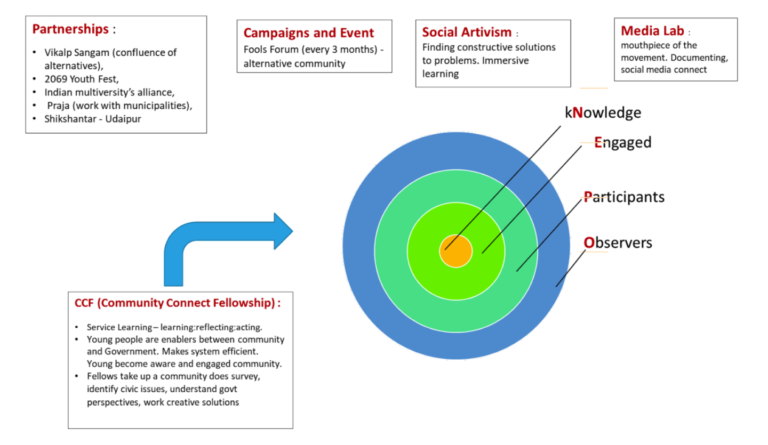

The process of Sarva-Anumati needs a structure that can make it accessible to a diverse group with diverse ways of being and engaging. We designed a system that factored in the interests of each individual, the amount of commitment each person would like to make, and yet be looped and together. We called it the OPEN system. It basically has 4 ways of engagement to keep our individual expectations with the group visible with enough flexibility. This structure can be visualized as oceaning or concentric circles without hierarchies.

OPEN System entails:

O: Observer

‘O’ members who are part of the movement but do not want to actively participate. They are happy to be in solidarity and in the loop of what’s happening.

P: Participation

‘P’ members choose to participate in the decision making process. The Proposals seek concerns, objections, if any, from this circle onwards.

E: Engaged

‘E’ members engage in ‘e’ circles/ adhyayan, support projects and initiatives. They participate in the decision making process too.

N: kNowledge

‘N’ members take active responsibility to think-be present to the functioning of the movement. They anchor the different verticals in the movement and initiate proposals for smooth functioning. They participate in the decision making process as well.

Members are free to move around as per their wish by just informing the larger group. While any new member who joins the movement, starts as an ‘O’ for 6 months to understand the decision making process while engaging as deeply as they wish.

Sarva-Anumati has enabled us to transition to a new way of being which is:

- Collectively owned, with a deep sense of ownership

- Enabling volunteers to be the decision makers of the direction of the movement

- Financially sustainable and decentralized

- In a year nurturing youth leaders who invested 3000+ collective learning hours, 4700+ action hours through 6 initiatives

Challenges that come up with this approach:

Any new process and humans do meet challenges. Some of the challenges or edges we hold with SAN are that it needs:

- investment of more time and energy to figure some that works for all

- patience to drop the urgency of ‘doing’ and immediately responding that the system throws at us

- deep commitment of every individual to stay with the process, communicate authentically and emerge

- capacity and time to deep dialogue/ adhyayans and holding space for conflicts

- capacity to hold complexity and nuances of diverse views to integrate them

“The topic of consequences is always a tricky one, especially when you’re one of the group members who’s deciding it for the entire community. A recent experience showed me that it takes things (processes + work) to actually go wrong before enough people see that such consequences are needed to be placed in. The SAN based community I’m part of works on the basis of ownership of the process and collective leadership. In order to function that way, learnings need to be shared so that the wisdom of the collective increases no matter which individual/s was present during any workshop/event. In case such sharing of learnings doesn’t happen, the group loses out on that knowledge. When such a barrier was seen during our last retreat it was suddenly obvious to everyone present that tough measures are required for certain situations. And our first disciplinary measure taking proposal was drafted at that instant,” shares Aniruddha who is part of the vertical that lays down the Internal Norms for the Movement

Akash Upase says “It made me realize one needs to let go of a lot of ego and surrender to the group process. That enabled me to detach comparatively from ‘my views’ about things and observe the power dynamics closely.

Sarva-Anumati is the counter flow (in terms of speed, process) to the current ways of working. It is one of the ways to challenge the current system. In spite of being counterflow, it accommodates and gives space for the voices of the current system as well which is normally missing.”

Pragmatic possibility of more SAN-based communities

Sarva-Anumati holds the possibility of creating an inclusive decision making process that could redistribute power. It needs each of us to practice this and birth the possibility in small pockets in our life, with small groups and communities.

You may want to start with trying 1 decision first. Sense how it feels, experience the struggles and joy. And step by step and maybe a few more decisions. While Brahma Vidya Mandir and Mendalekha may have the purest form of Sarva-Anumati – Sarv-Sahmati, we have adopted it to suit our context. We hold the deeper principles, with space to contextualize for our needs from a pragmatic lens to make it functional. Some of these functional insights and learnings have been:

- Choosing the process based on the nature of decisions to be taken. The O Model= the group convening, doing adhyayans (study), formulating proposals for the plan of action and waiting for objections on the proposal, without which those decisions are said to be taken by Sarva-Anumati. In times of confusion or urgency, choosing the A model= where one or two people are tagged by the group to decide for the group. Since the decisions are time sensitive, the group collectively gives Sarva-Anumati to let one or two people take decisions on behalf of the group. The group does this from a space of trust in the tagged person(s) to be in the best position, based on their expertise and experience to be able to take a decision that benefits the Movement at large.

- Design our own local system and use technological tools based on what is contextually relevant for us. Being a volunteer group diversely located into a city like Mumbai we had to design for light touch + virtual interaction.

- Decide on 2 cycles a year to initiate proposals. Considering the time limitations of a volunteer-led Movement, we decided to meet physically for a residential retreat twice a year to take stock of the various proposals that emerged through adhyayans through the year. This gave us structure to the process and free up the rest of the time to be able to action out the proposals.

- Distinguish Policy proposals from action proposals. Policy proposals are those that impact the entire Movement, its processes, norms, engagement and working. The action proposals focus on tangible actions that either the entire Movement, or a smaller group will carry out.

- Create space for urgent time bound proposals making Sarv-Anumati practically possible too. At times, we may not be able to push with external time constraints and it that time (very few times) can we take decisions based on existing understanding or trust the concerned person to decide and share their reasons.

- Set boundaries of decision on Sarva-Anumati that enables space for individuals and verticals creativity. Not all decisions require Sarva-Anumati of the entire Movement. There is some leeway given to the vertical anchors to fly with some decisions. This creates space for trust in the anchor’s creative freedom

So far, we have piloted and adapted Sarva-Anumati in 3 sister communities of BRM with a simple structure to suit its needs. We brought in Sarva-Anumati in both these communities with some rounds of consultation.

- Friends of BRM: This is a supporting community that contributes to BRM financially and in other ways. It is now practicing Sarva-Anumati for its major decisions since inception in 2019. It has enabled the community to feel included and take more responsibility as active supporters.

- ReLead community: It is a learning community of those who are alumni of ReLead’s program on personal growth. This community is at its nascent stages with just 6 months into it and figuring its own working through trial and error.

- SAYC community: The alumni community of South Asian Youth Conference is the newest addition to start practicing the spirit of Sarva-Anumati without the language since the beginning of 2021. This community deeply aligned to the spirit of coming together across borders and felt to hold the spirit in action without complicating it with language.

Some common learning across these communities has been the role of anchors is essential to bring the community together. Alongside with creating two options of engagement for the members as observers who support and active ones who prefer to engage in the thinking and decision making.

We believe more such communities can create their own versions based on their needs. For a future to emerge, we need to create small spaces for it to start emerging 🙂

ABOUT BRM

At Blue Ribbon Movement, we are an urban youth movement of volunteers living across the city of Mumbai. Over the years, BRM has built youth leadership through civic action in communities. It comprises several events, initiatives and an ongoing deep democracy process of ‘Sarva-Anumati’ or 100% consent to govern itself. We strive to create active citizens, creating non violent communities.

The BRM Journey began in 2001:

BRM 1.0 (2001-05) : An informal youth collective meeting weekly and doing community projects BRM 2.0 (2009-16) : A social enterprise that initiated fellowships, school programs and conferences BRM 3.0 (2017-Present) : A lifelong alumni-led Movement of system thinkers and doers who takes decisions with 100% consent.

We see change needed at three levels:

Me: Building leaders who are inclusive, self-aware and use non violent approaches

We: Alumni driving the Movement through collective leadership

Us: Building communities that support larger causes and stand in solidarity as system thinkers and doers

ABOUT AUTHORS

Kejal Savla

Kejal is the Convener of The Blue Ribbon Movement (BRM). A youth-led movement re-defining leadership structure and organizing itself as a movement with soul-forces of volunteers. It practices non-violent leadership through 100% consent based decision making by its members. The movement builds communities of alternative learning, action and dialogue through its events, programs and campaigns.

Over the past 7 years, Kejal has been part of facilitating and implementing its civic action program (The Community Connect Fellowship). It has built leadership in 400+ youth filing 6500+ civic complaints from local communities of Mumbai. She continues to support youth leaders who now lead initiatives in the movement.

Arnaz is an independent writer, editor and conscious-media professional.

An active alumni of the Blue Ribbon Movement – a space where the alumni are the decision makers – she is a part of a process that enables engaging with systemic critique. She started as a Community Connect Fellow (2015) and stayed on to volunteer and now leads the Movement’s Media. Having a Mass Media background and the deep desire to influence social change, at BRM, she created space for experimenting with a marriage of both.

Abhishek Thakore

Abhishek brings in over 15 years of experience in facilitation, design and transformational exercises.

Abhishek has facilitated learning journeys and programs for 50+ organizations across various sectors and geographies around the world. His approach combines a strong pragmatic focus on action along with insights into learning and change. His eclectic style draws freely from a range of disciplines including arts, theatre, philosophy, spirituality and body wisdom.

He has an MBA from IIM (Bangalore) where he was awarded the gold medal for the Best All-Round performance. He is trained in a range of methodologies including Appreciative Inquiry, NLP, Integral Theory, process work, Ontological approaches to leadership and theatre-based learning. He is also a Vipassana meditator, Process-based facilitator and the author of 3 books on personal growth. He currently channels a portion of his time catalyzing social change through The Blue Ribbon Movement which he co-founded in 2011 (www.brmworld.org)