By Giorgia Frisardi and Mattia Pellegrini

Foreword

“Who can forget those moments when something that seems inanimate turns out to be vitally, even dangerously alive? As, for example, when an arabesque in the pattern of a carpet is revealed to be a dog’s tail, which, if stepped upon, could lead to a nipped ankle? Or when we reach for an innocent-looking vine and find it to be a worm or a snake? When a harmlessly drifting log turns out to be a crocodile?”

(Amitav Ghosh, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable)

“ …you don’t know how many witches they burned and how many women ended up filling psychiatric asylums before they realized it was a severe autoimmune thyroid disease”.

(With these words, a doctor from the Roman suburbs introduced me, for the first time, to the disease I’m suffering from.)

The “scenario” is what usually allows stories to unfold. The relationship between scenario and action is as close as that between theatre and play.

The landscape of this story is its articulation, my own story, the story of the illness that has stretched me, the story of the disease that has put me down me and curled me up. It is jotted down in meetings, events of reappropriation of public space, claims of impossible monstrosities, and other related and strange situations.

I take these fragments among the pages I have written in these last two and a half years of illness.

The transition from a political and always public life, a transfeminism made of assemblies, pickets and performances in occupied spaces, to the inability to move from my bed.

From acute hyperthyroidism to the attempts to fight it.

When you are chronically ill, you have to constantly tell the world that you don’t want to be as such, you have to constantly represent your attempt of recovering.

There is always someone who suddenly wants to suggest the solution, convinced that you are not already trying everything.

On top of everything, those not sick always hover with the feeling that you’re not doing enough, that you’re lazy, that it’s not possible for an illness to be so terrible.

It might be the fear, it might be the privilege, it might be the separation that our culture has produced, even in regard to what one has to do for their own well-being or with one’s own sickness, even on what being well consists of.

ABLEISM is one of the intersections of oppression with which we must urgently come to terms. Even among feminists.

If the disease, as in my case the Basedow’s disease, in addition to tearing apart the body, affects in an even more decisive manner the emotions, the relational skills, producing anger, psychosis – the question becomes even more complex, the issue becomes a chasm.

You are a crazy person, and so you have to be treated.

The practices of anti-psychiatry, to be near by, to stay present instead of judging. It’s not easy. It never is.

For a long time now, therefore, I have felt the urgency to publish what I have been going through, to publish my side of the story. I immerse myself in pages written and forgotten, intimate and at the same time so foreign.

“The number one lesson I have learned as a writer: Don’t let people remove you from your own story. Be ruthless, even if it is your own mother.”

(Meena Kandasamy. “When I Hit You”. Atlantic Books)

I spend a forastic, voracious night re-reading everything. And I collapse, collapse again.

I enter into such deep agony the very day after I was finally able to leave the house, after a month in bed.

Chronic illness teaches us a profound critique of the progressiveness.

Writing about one’s illness should start with this: the hand to hand with a part of oneself that is not willing to make your life livable. And it is not a matter of corroborating the vision of Western medicine that autoimmune diseases are the body going against itself.

It’s something less mysterious. The poison is environmental. It propagates from patriarchy, from fatphobia, from racism, from sexism, from precariousness.

It’s not my body that goes against itself but the system-world, the capitalist world, it’s capitalism that does everything it can to get me out of its way.

It’s frustrating, it’s painful, I would like to fight but I don’t have the strength.

So we decide to write in two, the other half going through this tortuous adventure with me. Mattia.

My body is a sick body, my body is the field of the radical critique of the present.

My body would like to lash out against the allopathic medicine to which I had to submit, which deprived me of an organ to save me and then, satisfied, disappeared.

My body is vulnerable.

Chronic disease teaches us the inoperative potency of vulnerability.

And never before, now that my body is so sick, do I know it, in each of its meridians, in each of its cartilages, in every void.

Never as before, now that my body is so sick, I determine my political and poetic position.

Here is the scenario, here is the story.

Among the titles of various texts, there are two diaries in which I have tried to force myself to write: Cortisone Diary, Tapazole Diary.

I had thought to include those, but instead you will find no trace of them. We have absorbed those words and something else was born out of them.

This short text wants to be a prelude for a common reflection, singular and collective at the same time, on the practices of care that are possible and that can overflow duality and embrace the unexpected.

We are trying both to save ourselves, we are doing these by being two-together, even if we understand well the critique of heteropatriarchy.

We couldn’t do it otherwise, and the support that we expected from those in certain militant circles has broken down, apart from very rare cases.

Very rare and magnificent so intimate that there is no need to name names.

We are in exile on a lunar station.

On this basis, helping others is really complicated.

We are with Silvia Federici when she foments a community of care that does not isolate, that takes charge of the other, when she encourages us to explore new territories together.

This also means to not force fragility to turn into enemy territories such as certain forms of stability, certain forms of living, certain behaviors.

We are with Virginia Woolf, Audre Lorde, Sunaura Taylor, Feminoska and all, all those whose names we do not know.

We are with Johanna Hedva who in “Sick of Woman Theory” fully captured my feeling of powerlessness with respect to a militant subjectivity:

So, as I lay there, unable to march, hold up a sign, shout a slogan that would be heard, or be visible in any traditional capacity as a political being, the central question of Sick Woman Theory formed: How do you throw a brick through the window of a bank if you can’t get out of bed?

On this question we question ourselves, with this question we join all the sick women of this world.

Let us start from the crisis of the healthy subject, always male, always white from which even the antagonistic politics can hardly free itself from.

Let us start from vulnerability from the criticism of rectitude, to make the present explode.

For a right to approximation.

Some notes

I tried 1000 times to venture on this text.

Thoughts burn a particular part of the brain, they immediately become past, confused and blurred.

I have little strength and if I accept it I can’t loose any random chance. That terror that it is to see when the words finally condense- exhilarates and exhausts me.

If I react, if I make an effort, afterwards I die a little of an exhaustion that lasts for weeks.

I am allowed only the fragment, spasms of thinking that is made up of an intimate, anarchic bewilderment.

There are words far removed from any universalism that I say to myself in this polyphonic and extended solitude that is synonymous with caginess.

I am so far from when I used to sing for others, it is a continuous singing to myself, tiny whispering and companionship in the staircase, to chase away fear, as when i was a child, or today to chase away the physical pain that holds me and never leaves me. It’s an ongoing job.

You would have to pay me to keep myself alive.

After my diagnosis, I read a mountain of essays, to feed myself of finite, circumscribed, just knowledge. To put chaos before some form is made. Then it happened that theory is nothing without the world. It became clear to me when I lost every possible interlocutor in the endless nights of contractions and pain. And then, it happened that theory began to build worlds, through friendships and impossible encounters. Chronic illness is a hermitage.

Disabled scholars and activists have long theorized the idea of “crip time.” Crip time means many things to many people and acknowledges that we live at different speeds, that our very sense of time is shaped by our experiences and abilities. Time is relative. Writer and disability activist Anne McDonald describes her sense of time: “I live life in slow motion. The world I live in is one where my thoughts are as quick as anyone’s, my movements are weak and erratic, and my talk is slower than a snail in quicksand.” Disability fosters a different sense of pacing, of progress, sometimes even of life span. If time can change so drastically for those of us for whom mundane tasks such as getting dressed, preparing a meal, or speaking take longer, then how might time be reconceptualized for those who have profound intellectual differences or for the great variety of animals?

(Sunaura Taylor, Beasts of Burden: Animal and Disability Liberation, The New Press.)

And if I see little of the world, I see the world that I can when always burdened by the organization of my organs, while I finally manage to raise my eyes to the sky, it is a sky filtered by a sick body and then I see the sky and feel the eyes, pain is also a beautiful device to feel more and my hands, which shake from within, and everything else contracts.

Then pain is a lens that sees the world, also what is invisible in it, and much deeper than it appears.

Wet

I reached back to literature, like when I was a little girl at the beach, and I had three months to bury my self in books to read and a mountain of stories, itches and ideas to shape my body. And to swim how I always wanted to swim.

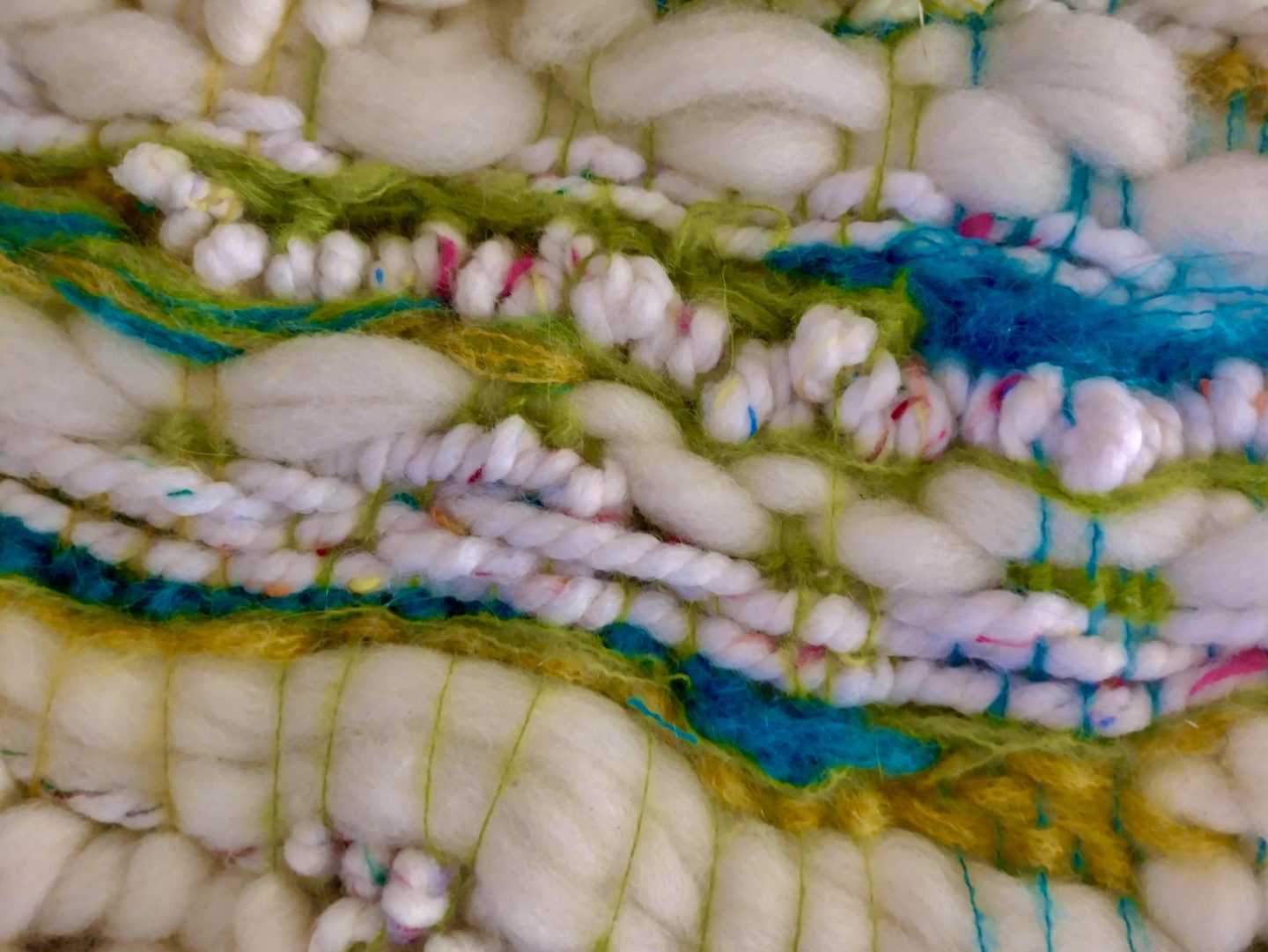

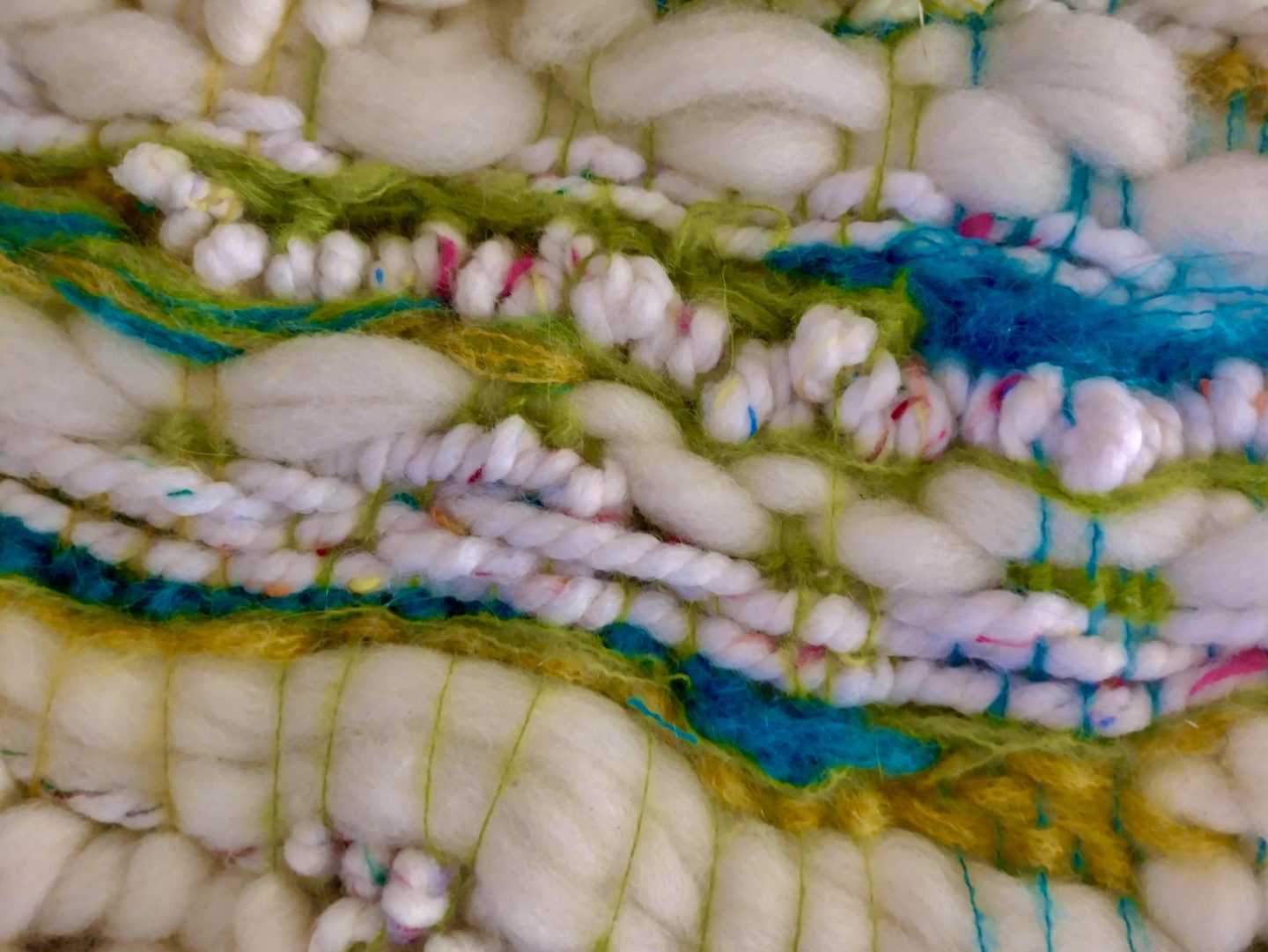

When I tried again in this sick me, the water became more water, very dense and sparkling, it exhausted me to the point of understanding perfectly that my disease is a disease of the wet, as they have understood in other cultures, those that have other ways of healing, better ones than those used in the West where everything is dissected, dismembered, here everything is conceived for a unique body and same to itself.

A disease of the body that does not rebalance itself because it is too full of humidity. I got cold. I didn’t know how to protect myself from the signal that has marked the anthropocentrism of the primary goods. Covering up.

I can smell the musty stucco corner when I think about it. I need to dry myself and keep warm in those blankets used to wrap migrants at sea. What an effect of colonial light must give that mirrored isotherm material created with machines and chemistry.

And what a small founding pleasure to finally be able to cover yourself when you’ve been wet for days, with seawater that burns and not even a handhold to rest on.

I learned to use wool and not acrylic for my restless insulation. White privileges, I can estrange myself from the body and on wi fi I can study every relief for every symptom.

I remember lying down that everything would fall out of my hands and then I couldn’t cook or read or think because when your your hands hurt to the point of losing sensitivity you have access finally to the world lying down, which is opposed to the righteousness of the statues of rapists and imperialists that were destroyed outside while I basked in the proudly iconic posture I could assume.

Horizontal Revolution Bedridden in opposition to the obelisk totem of things they do. That they say. That they know.

Unbalanced, falling backwards, due to one of my will, which is still mine. Due to my body that compels me and says at the same time lay down, because this ascent, this fatiguing opposition to gravity, does not suit us.

I prefer myself naked on a dormeuse smoking opium. I’d rather lead the crew with bare breasts.

The organs reorganize themselves when you no longer assume the upright position for a long time. They accommodate themselves in the postures of the exhaustion you assume because you can’t do anything else.

So when you can stand up, everything moves and you feel finally that you have a heart and a stomach and liver that vibrates and when the intestine stops moving is an event, majestic event.

(for a) thyroid landscape

in sickness and study

it can take

many earth years

to molt

rooting perpetual paws

sensational suckers

that rest a kiss on crooked things

and walk only by force of loving leverage.

Mediating continuous assault and normed proxemics.

in sickness and study

I, the sick, adore and abhor myself.

I, incarnated monster,

suffering, spotted.

I hold up a mirror of green wounds

They reflect me as an alien

but at a leap from the world

in sickness and study

The time when the catastrophe has already happened

in which I have turned somersaulting

on ripe strawberry legs and mold

end of the body of the dance

end of the body of the sense

end of the body I had chosen.

in sickness and study

Then a tangle, a stumble in disarray

of viral ascent in the petrified city

end of possible bodies

end of accessible breaths

an enchantment of State

invested and adorned

of deviated carrion

the entire apparatus.

in sickness and study

I write voracious, broken to the chest

I write quivering bitch

dug tearing through meager burrows

pneumatic shelters that only by oversight figure things

I write cleanly

and surgeon to the abject

I hold a sigh

on the tip of the pubis

in precarious balance

divaricate oblivion.

It is a torment of sorts

always getting disoriented

woman and fish remedy

and blood and plasma

and chlorophyll and light

and a single, tiny handhold

in wood

to stay afloat.

I have found a refuge

that is escape,

finally.

(poem by Giorgia Frisardi in Postural Epistemologies)

Di Giorgia Frisardi e Mattia Pellegrini

Premessa

“Chi può dimenticare i momenti in cui qualcosa che sembrava inanimato mostra di essere ben vivo, addirittura pericolosamente vivo? Ad esempio quando un arabesco nel motivo di un tappeto si rivela come la coda di un cane, che, se calpestata, potrebbe provocare un

morso a una caviglia. O quando, allungando una mano verso un tralcio d’aspetto innocuo, scopriamo che è un grosso lombrico o un serpente. O quando ci accorgiamo che un inoffensivo tronco galleggiante in realtà è un coccodrillo”.

(“AMITAV GHOSH, LA GRANDE CECITÀ. Il cambiamento climatico e l’impensabile”, Neri Pozza Editore, 2011, pag.11)

“che non sai quante streghe hanno bruciato e quanti manicomi femminili hanno riempito prima di capire che era un grave morbo autoimmune della tiroide”

(Con queste parole, un dottore della periferia romana, mi ha fatto conoscere, per la prima volta, la mia malattia).

Lo “scenario” è ciò che di solito consente alle storie di avere uno svolgimento; il rapporto tra scenario e azione è stretto quanto quello tra palcoscenico e opera teatrale.

Il paesaggio di una storia è il suo articolarsi, la mia storia, quella della malattia che mi ha distesa e raggomitolata si appunta in incontri, eventi di riappropriazione dello spazio pubblico, di rivendicazioni, di mostruosità impossibili e altre vicende correlate e strane.

Prendo questi frammenti tra le pagine che ho scritto in questi ultimi due anni e mezzo di malattia.

Il passaggio da una vita politica e sempre pubblica, quel transfemminsmo fatto di assemblee picchetti e performance in spazi occupati, all’impossibilità di muovermi dal letto.

Da un ipertiroidismo acuto al tentativo di contrastarlo.

Quando sei un malato cronico devi costantemente ribadire al mondo che non vuoi esserlo, devi costantemente rappresentare il tuo tentativo di guarigione.

C’è sempre qualcuno che improvvisamente vuole suggerirti la soluzione convinto che non le stai già provando tutte. Sul fondo del non malato aleggia sempre il sentimento che non stai facendo abbastanza, che sei pigra, che non è possibile che una malattia sia così tremenda. Sarà la paura, sarà il privilegio, sarà la separazione che questa cultura ha prodotto anche su ciò che ha che fare con il proprio star bene, anche su ciò che ha che fare con il proprio star male.

L’abilismo è una delle intersezioni dell’oppressione con cui dobbiamo fare più urgentemente i conti. Anche tra compagne.

Se la malattia, come nel mio caso il Morbo di Basedow, oltre che fare a pezzi il corpo agisce, in maniera ancora più determinante, sulle emozioni, sulla rabbia, sulle capacità relazionali, sulle psicosi, la questione è ancora più complessa, la questione è una voragine.

Sei una matta e così devi essere trattata.

Bisognerebbe riprendere in mano le pratiche dell’antipsichiatria, rimanere a fianco, accogliere invece di giudicare.

Non è facile. Non lo è mai.

Da molto tempo sento quindi l’urgenza di pubblicare ciò che sto attraversando, di pubblicare la mia versione dei fatti.

Prendo questa occasione per farlo, mi immergo in pagine scritte e dimenticate, intime e allo stesso tempo così estranee.

“Non lasciare che qualcuno ti elimini dalla tua storia. Sii spietata, anche se si tratta di tua madre”

(Meena Kandasamy. “Ogni volta che ti picchio”. Edizioni e/0, 2017, pag 18)

Passo una notte forastica e vorace a rileggere tutto.

E crollo, crollo ancora.

Entro in un agonia così profonda proprio il giorno dopo che ero riuscita ad uscire finalmente di casa dopo un mese continuo di letto.

Le malattie croniche ci insegnano una profonda critica alla progressività.

Scrivere della propria malattia dovrebbe partire proprio da questo: il corpo a corpo con una parte di sé che non ci sta a renderti la vita vivibile. E non si tratta di corroborare la visione della medicina occidentale per cui le malattie autoimmuni sono il corpo che va contro se stesso.

È qualcosa di meno misterioso. Il veleno è ambientale. Propaga dal patriarcato, dalla grassofobia, dal razzismo, dal sessismo, dal precariato.

Non è il mio corpo che va contro se stesso ma il sistema-mondo, il capitalismo che fa di tutto per togliermi di mezzo.

È frustante, è doloroso vorrei combattere ma non trovo le forze.

Decidiamo allora di scrivere in due, l’altra metà che attraversa con me questa tortuosa avventura.

Mattia.

Il mio corpo è un corpo malato, il mio corpo è il campo della critica radicale al presente che c’è dato vivere. Il mio corpo vorrebbe scagliarsi contro la medicina allopatica a cui sono dovuta sottostare, che mi ha privato di un organo per salvarmi e poi, soddisfatta, s’è dileguata.

Il mio corpo è vulnerabile.

Le malattie croniche ci insegnano la potenza inoperosa della vulnerabilità.

E mai come adesso che il mio corpo è così malato io lo conosco, in ogni suo meridiano in ogni sua cartilagine, in ogni suo vuoto.

Mai come oggi, che il mio corpo è così malato, determino la mia posizione politica e poetica.

Ecco lo scenario, ecco la storia.

Tra i titoli dei vari scritti vi sono due diari in cui ho cercato di costringermi alla scrittura:

Diario del cortisone, Diario del Tapazole. Avevo pensato di inserirli e invece non ne troverete traccia. Gli abbiamo assorbiti e ne è nato qualcosa di altro.

Questo breve testo vuole essere il preludio ad una riflessione comune, singolare e collettiva, sulle pratiche di cura possibili che esondino la dualità e abbraccino l’imprevisto.

Ci stiamo tentando di salvare in due seppur comprendiamo bene la critica all’eteropatriarcato. Non ci siamo riusciti a fare altrimenti e l’appoggio che ci aspettavamo da una certa militanza si è scomposto a parte rarissimi casi.

Rarissimi e magnifici, talmente intimi per cui non c’è bisogno di fare i nomi.

Siamo in esilio su una stazione lunare.

Siamo con Silvia Federici quando fomenta una comunità di cura collettiva che non isoli, che si faccia carico dell’altra, che insieme si possano esplorare nuovi territori.

E questo significa anche non costringere le fragilità a ritorcersi su territori nemici quali certe forme di stabilità, certe forme di abitare, certe forme di comportamento.

Siamo con Virginia Woolf, Audre Lorde, Sunaura Taylor, Feminoska e tutte, tutte quelle di cui non conosciamo il nome.

Siamo con Johanna Hedva che in “Teoria della Donna Malata” ha colto pienamente il mio sentimento di impotenza rispetto ad una soggettività militante:

“Così, mentre me ne stavo distesa a letto, incapace di sfilare in corteo, di tenere in mano un cartello, di gridare uno slogan per farmi sentire, o di essere visibile in qualsiasi altra forma tradizionale come essere politico, ha preso forma la domanda centrale della Teoria della donna malata: come si fa a lanciare un mattone contro le vetrine di una banca se non puoi alzarti dal letto?”

Su questa domanda ci interroghiamo, con questa domanda ci uniamo a tutte le malate di questo mondo.

Che si parta dalla messa in crisi del Soggetto sano, sempre maschio, sempre bianco ma da cui anche la politica antagonista difficilmente riesce a liberarsi.

Che si parta dalla fragilità, dalla critica alla rettitudine, per far esplodere il presente.

Per un diritto all’approssimazione. Qualche appunto

Ho tentato 1000 volte ad azzardarmi su questo testo.

I pensieri bruciano una particolare parte del cervello, si fanno subito passato, confuso offuscato.

Ho poche forze e se lo accetto non posso pescare nessuna casualità a casaccio.

Quel terrore che è vedere quando finalmente le parole si condensano, mi esalta e mi sfianca.

Se reagisco, se mi sforzo, dopo muoio un po’ di una fatica imprendibile che dura settimane.

Mi è concesso solo il frammento, spasmi di cogito che è fatto tutto di un intimo sconcerto anarchico.

Sono le parole lontanissime da qualsiasi universalismo che mi dico in questa solitudine polifonica e distesa che è sinonimo legaccio della cagionevolezza.

Sono così lontana da quando cantavo per gli altri, è un cantarmi continuo, minuscolo, sussurro e compagnia per le scale, per scacciare la paura, da bambina, o per scacciare, oggi, un dolore fisico che trattiene e non mi molla mai.

È un lavoro continuo.

Dovreste pagarmi per farmi tenere in vita.

Dopo la diagnosi ho letto una montagna di saggi, per nutrirmi di saperi finiti, circoscritti, giusti. Per anteporre al caos una qualche forma fatta. Poi è avvenuto che la teoria non è niente senza il mondo. Mi è stato chiaro quando ho perso ogni interlocutore possibile nell’infinite notti di contrazioni e dolori. E poi è avvenuto che la teoria ha iniziato a costruire mondi, attraverso amicizie ed incontri impossibili.

È un eremitaggio la malattia cronica.

Gli studiosi e gli attivisti disabili hanno a lungo teorizzato l’idea di un tempo crip. Tempo crip significa molte cose per persone diverse, e riconosce che viviamo a velocità diverse che il nostro stesso senso del tempo è modellato dalle nostre esperienze e capacità. Il tempo è relativo. (…) La disabilità promuove un diverso senso di ritmo, di progresso, a volte anche di durata della vita. Se il concetto di tempo può cambiare così drasticamente per quelli di noi per cui compiti banali come vestirsi, preparare un pasto o parlare richiedono più tempo, allora come potrebbe essere riconcettualizzato il tempo per coloro che hanno profonde differenze intellettuali o per la grande varietà animale?

(Sunaura Taylor. Bestie da Soma. Disabilità e Liberazione Animale. Edizioni degli Animali, 2021, pag. 206/207 )

E se di mondo ne vedo poco, vedo il mondo che posso e quando posso, sempre oberata dall’organizzazione dei miei organi, mentre finalmente riesco ad alzare gli occhi al cielo, è un cielo filtrato da un corpo malato e allora vedo il cielo e sento gli occhi, che il dolore è anche un dispositivo bello per sentire di più, e le mani, che mi tremano, ma da dentro e tutto il resto si contrae.

Allora il dolore è una lente che vede quanto è più fondo e invisibile di come appare, il mondo?

Umido

E mi sono rifatta alla letteratura, come quando ero ragazzina al mare e avevo tre mesi di libri insabbiati da leggere e una montagna di storie, di prurigini e idee da plasmarmici il corpo. E nuotare, quanto vorrei sempre nuotare. Quando ho tentato, in questa me malata, l’acqua si è fatta più acqua, densissima e frizzante, mi ha spossato al punto da intendere perfettamente che la mia malattia è una malattia dell’umido, come hanno colto in altre culture, altre vie del guarire più a oriente, meglio che qui dove tutto è sezionato, smembrato, qui dove tutto è concepito per un corpo unico e uguale a se stesso.

Una malattia del corpo che non si riequilibra perché troppo pieno d’umidità. Ho preso freddo. Non ho saputo proteggermi dal segnale che ha contraddistinto l’antropocentrismo dei beni primari. Coprirsi.

Sento l’odore dell’angolo di stucco ammuffito quando ci penso. Ho bisogno di asciugarmi al caldo in quelle coperte drag con cui avvolgono i migranti in mare. Che effetto di luce coloniale deve dare quell’isotermia specchiata creata con le macchine e la chimica.

E che piccolo piacere fondativo poter finalmente coprirsi quando si è bagnati da giorni, di acqua di mare che brucia e neanche un appiglio per potersi posare.

Ho imparato la lana e non l’acrilico per la mia irrequieta coibentazione.

Privilegi da bianca che posso estraniarmi dal corpo e studiare via wi fi ogni sollievo per ogni sintomo.

Mi ricordo distesa che ogni cosa mi cadeva dalle mani e allora non potevo cucinare o leggere o pensare perché quando le mani ti dolgono al punto da perdere la sensibilità hai accesso finalmente al mondo sdraiato, che si oppone alla rettitudine delle statue di stupratori e imperialisti che fuori distruggevamo mentre io mi crogiolavo nella postura fieramente iconica che potevo assumere. Rivoluzione orizzontale. Costretta a letto in opposizione all’obelisco totem delle cose che fanno. Che dicono. Che sanno.

Sbilanciata, caduta all’indietro per una delle volontà che è pur sempre mia. Del mio corpo che mi costringe e dice insieme sdraiati che questa ascensione, questo opporsi affannoso alla gravità non ci si addice. Mi preferisco nuda su una dormeuse fumando oppio. Che retta a guidare le ciurme a seno nudo.

Gli organi si riorganizzano quando non assumi più la posizione eretta per lungo tempo. Si accomodano nelle posture della spossatezza che assumi perché non riesci a fare altro. Quindi quando riesci ad alzarti tutto si muove e senti finalmente che hai un cuore e uno stomaco e il fegato che vibra e l’intestino che quando smette di muoversi è un evento maestoso.

(per un) paesaggio tiroideo

in sickness and study

si possono impiegare

molti anni terrestri

per fare una muta

radicare zampe perpetue

ventose sensazionali

che poggino a bacio su cose storte

e camminino solo a forza di leva amorosa.

Mediando continuo assalto e normata prossemica.

in sickness and study

Io malata mi adoro e mi aberro.

Io mostro incarnato

dolente, maculato.

Ho teso uno specchio di verdi ferite

mi riflettono aliena

ma a un salto dal mondo

in sickness and study

Il tempo in cui la catastrofe è già avvenuta

in cui ho girato capriola malferma

su gambe fragole mature e muffa

fine del corpo del ballo

fine del corpo del senso

fine del corpo che avevo scelto.

in sickness and study

Poi un groviglio, un inciampo a scompiglio

di virale ascesa nella città impietrita

fine dei corpi possibili

fine di respiri accessibili

un incanto di Stato

ha investito e adornato

di carogne deviate

l’intero apparato.

in sickness and study

scrivo vorace, spezzata al torace

scrivo cagna fremente

scavata stracciando magre tane

rifugi pneumatici che solo per svista

figurano cose

scrivo di netto

e chirurga all’abietto

tengo un sospiro

sulla punta del pube

in equilibrio precario

divaricato oblivio.

È un tormento di specie

disorientarsi sempre

rimedio donna e pesce

e sangue e plasma

e clorofilla e luce

e un solo, piccolissimo appiglio

in legno,

per restare a galla.

Ho scovato un rifugio

che è fuga,

finalmente.

(poesia di Giorgia Frisardi in Epistemologie Posturali)