How it all started

Once upon a time, in my teenage years, my plan was to start an engineering company and make piles of money. But the Polytechnic University of Bucharest – the first step of the plan – wasn’t the passionate and creative place I hoped for. By the third semester, I was trying to convince some colleagues to build a website where to express our dissatisfaction. The many complaints I was voicing were underlined by a deeper frustration: why don’t we, the students, have a say in our own education?

By the fourth semester, I was joining our local student union and soon after the board of a national federation of student unions. I found myself writing an open letter to the dean, organizing a march of 2000 students and organizing a campaign in 15 universities to promote the Bologna Process – an initiative to harmonize and transform higher education in Europe. Fast forward another year I was representing students in the Board of Romanian Agency for Quality Assurance in Higher Education, struggling to introduce student centered learning criteria in their methodologies and to have students as equal members in the study visit teams that evaluate the universities.

Our Bologna Process campaign was named “the best education and research project of 2006” in Romania and we did succeed to have students as equal members of the study visits of the QA Agency. There were other signs that our efforts were decent, but nothing in these five years of activism showed any sign that Romanian state universities were shifting, even just a little tiny bit, to become more “student-centered”.

The shift happened inside me. I came to the university with the dream to make money, to buy a house by a lake and drive a sports car. But if I would have won the lottery as I was graduating, there was one thing I would have done: build a totally different university. Slowly, over the years of student activism, transforming universities so that students determine their own learning became my passion and my mission in life.

So, as my classmates were getting jobs after graduation, me and four other former student activists were setting out build “a university of the students”. We started by setting up an NGO and working with 20 volunteers from 10 youth organizations. We were facilitating their peer to peer learning around how they were recruiting and integrating new members in their organizations. The community grew past 100 members and we introduced a counseling for self directed learning program, a mentorship & coaching program, a yearly camp, workshops, small-group courses and weekly guest speakers.

In 2012 we rented and renovated a villa with a nice garden and added a business incubator, a Harry Potter like game for community building, learning days, a system of badges, communities of practice, and a “graduation celebration”.

El pase de diapositivas requiere JavaScript.

Starting in 2013, we named it The Alternative University and our student guide described a “model of learning” built around four principles: self-determined learning, real life projects, communities of practice and nurturing a value-based learning tribe.

The call to adventure

In 2014, the Alternative University had 178 students, a core-team of 9 full-time people and 12 part-time volunteers.

The annual event where the whole community gathered – the Camp – was the most important and awaited moment of the year. Because we always had the vision of handing over the university to the students, in the summer of 2014, for the first time, a team of mostly students were organizing the seven day Camp. The team decided to change the beautiful location we were used to. This made me think that the camp would be a failure.

Three days into the camp I realised it was the best we had ever had and I was experiencing a feeling of freedom that seemed to be coming from a different life. Making the Alternative University happen had been consuming all of my energy for the past 7 years. In a twist of irony, I had became a self-chained slave of the freedom centered university. So the feeling that the university could have a life of its own gave me the sweet taste of the liberation that was becoming possible.

In the last day of the Camp, a day dedicated to “daring”, we stood in a big circle and each of us shared one thing that we would dare to do the following year. I said that I would leave the Alternative University’s core-team to travel around the world and write a book. The idea was sudden and the decision took me seconds. I announced it before pondering it. But the more I was thinking about it, the more it made sense. It was good for me to pause, reflect, rest, refresh and deepen my ideas about learning and learning architectures. I had been bookmarking innovative universities and schools for years, without having the time to research them deeper. Also I had a longing to go on an adventure to discover the world and to understand it better. For the Alternative University it was time to refresh and see how the ecosystem we nurtured could flourish beyond the day to day involvement of the founders.

In August 2015 I was leaving Romania, only to come back 2 years later after visiting 19 countries and more than 100 projects. The crowdfunding campaign I did back in 2016 captures my intentions and questions at that time:

I believe that the world needs to take a turn from the current direction. There are 2.3 billion people under 20 and 23,729 universities. These universities will not have enough places. Even if they did, their economic model is too expensive for many more people to afford to go. And even if we had resources, we know that their learning model is ineffective, even counterproductive, in nurturing the entrepreneurial changemakers that could steer the world in another direction.

I see myself as part of a global tribe of people that played for a long time at the edges of higher education. Long enough to know that something radically better is possible at a big scale: universities that are inexpensive, accessible to many more and effective in nurturing people to flourish and transform their world. I will travel to gather stories from all continents of the world about individual learning journeys, radical learning architectures, communities, hubs, hackerspaces, rituals and neat tech tools. The journey is more than a documentation for the book. It is a quest for inspiration, connection and my personal transformation, guided by questions like: How do the 7 billion people on Planet Earth live together? What is important to them? How do these people get good at living life? How can the 23,729 universities in the world help the two billion people under 20 to flourish and transform our world?

Eight “explorations” at the edges of higher education

My questions back in 2016 seem to be broad but my actual spectrum was narrower. I was focused on finding ways of making the learning process more self directed, more self-organized and more powerful. At that time, I didn’t see any problem with the dominant knowledge system – I was taking it for granted. As I was traveling, my interest grew around questions of the nature of knowledge, different ways of knowing and being, different worldviews and what is individual and collective wisdom as we travel into the unknown.

Before leaving, the context that was alive for me was the urban and relatively privileged one. As I was traveling, I started asking questions around how less privileged communities can develop their own learning and unlearning capacities. The issue of decolonisation and social justice became important. My focus moved away from transforming education/learning towards a more systemic view of the transformation of our economic system and our broader culture.

Among the many places I visited, there were some where my perspective broadened in unexpected ways. I put together a list of eight of the places that mostly inspired me. Each place is a rich universe of ideas and practices, but I will only highlight one insight that each provoked. I’m naming the insights using the present participle of a verb to suggest that these living experiments at the edges of higher education describe part of humanity’s boldest ongoing exploration into what universities might become. The eight explorations are Unlearning, Resignifying, De-institutionalizing, Action-Researching, Open-Sourcing, Isolating, Designing&Building and Playing. I like to think that these verbs do not describe a path forward but a way of walking forward into the unknown.

Unlearning: Universidad Swaraj (Rajasthan, India)

Swaraj hosts 2 batches of up to 20 khojis (=explorers) for a 2 year learning journey. In contrast with its size, I found this tiny place to be an immense statement about deschooling society, unschooling our minds and creating a beautiful and just society.

The overall theme of Swaraj is unlearning and it comes up in many forms. The campus is zero waste and plastic free. The food is vegetarian, there is no smoking, alcohol or drugs on campus. Each of us would wash our dish in a system of buckets to minimize the water consumption. Everything is organic. Not only they don’t have diplomas, but they playfully provoke the idea with a national campaign titled “healing ourselves from the diploma disease”; Another of their provocations is to say that you can’t teach at Swaraj if you have a Phd. Manish, one of the founders, often says that he learned more from his illiterate grandmother than from studying at Harvard.

As a visitor, I was given one of the two guest rooms for 12 days and I was invited to eat with everyone else, but there was no price per night. When I asked they said “give whatever you can from your heart”. Unlearning your relationship with money and practicing gift culture was amongst the most insightful instigations that Swaraj offered me. One way they do the same for students is Cycle Yatra: a week-long bicycle trip through indian villages without phone, money or food. Also striking is their disinterest and even aversion to the idea of scaling up.

Originating from Gandhi’s thought on freedom and decolonization, the gift that Swaraj has to offer the world is its focus and beautiful designs and metaphors around unlearning. Unlearning to overvalue institutionalized knowledge, to be controlled by your fears around money, to consume more than you need, to eat junk food, to produce waste, to undervalue the small. Unlearning becomes the central means for young people to free their imaginations, create their place in the world and give birth to a more just, sustainable and beautiful world.

Re-signifying: Universidad Campesina Indígena (Puebla, Mexico)

UCI-Red is a small team dedicated for over 35 years to nurturing educational projects for and with the rural and indigenous population of Mexico. What started as a primary school in Zautla, a small village in Sierra Norte de Puebla, led up to several bachelor degrees and various development projects grouped under the umbrella of CESDER – Center for Studies in Rural Development. This organization is now run by ex-students of the bachelor programs while part of the initial team went on to form the Rural Indigenous University Network (UCI-Red) that organizes master programs, short courses and offers consulting in education design.

What I found hugely inspiring is a philosophy around education they call “pedagogia del sujeto” that continues Paulo Freire’s thinking (pedagogy of the oppressed) and not only brings it to the context of today’s Mexico but also enriches it in a lively dialogue with some of the world’s most profound philosophers of the spanish speaking world. What emerges is a poetic way of reframing “education” as an act of empowerment, or as they say: “making ourselves subjects”. It’s a pedagogy that emerges from a conversation around a question such as “How is life going for us?”. It is not an innocent question. It brings along what they call an epistemic displacement: “Before asking what is life, we ask how is life right now, for us. We are included.”

Summer course of Universidad Campesina Indigena, in Sierra Norte de Puebla

They also say that “education is the gift of time, because we are time. Education is opening spaces of conversation. Conversation is to give the ear first and then to give your word.” Because of this approach, roughly one third of the students give up in the first months saying “to have a conversation I can go home, here I come so others can tell me how it is.” The ones that stay say: “This is a place where we can express ourselves” and “I have learned how to rename the old labels and to resignify living life.”

Reframing, renaming of labels or resignifying known ideas and practices into joyful, creative and fertile perspectives is the trick that seduced and inspired me. In a harsh and violent context where “resistance” and “changing the world” are imperatives for making life breathable, they speak about a “joyful way of changing the world” and they let a chicken determine the grades of the students. In an absurdly brutal reality, they flirt with “delirium” as a coping strategy. When asked about the power dynamics, they reframe the conversation into “the fertility of the relationship”. They reframe their designs as “artilugios” (gimmick or stunt). Local development, is no longer understood as UN or World Bank advertised (focused on having running water for example) but more like living with dignity, in harmony with nature, family and community. As a former student put it “UCI taught us how to be revolutionaries in our own day to day life“.

De-institutionalizing: Unitierra (Oaxaca & Chiapas, Mexico)

Unitierra was founded in 2001 in Oaxaca City by Gustavo Esteva, Sergio Beltrán and others, around one core principle: learning by doing. It emerged to serve a need of the indigenous communities that were rejecting the dominant state-supported education. In Gustavo’s words: “We don’t have education, we are escaping education. Accepting education equals accepting the authority of an educator.” They note the destructive effect education has on indigenous culture: “You can survive as an indigenous up until university but it is almost impossible to survive after going to university. Your indigenous soul is gone.”

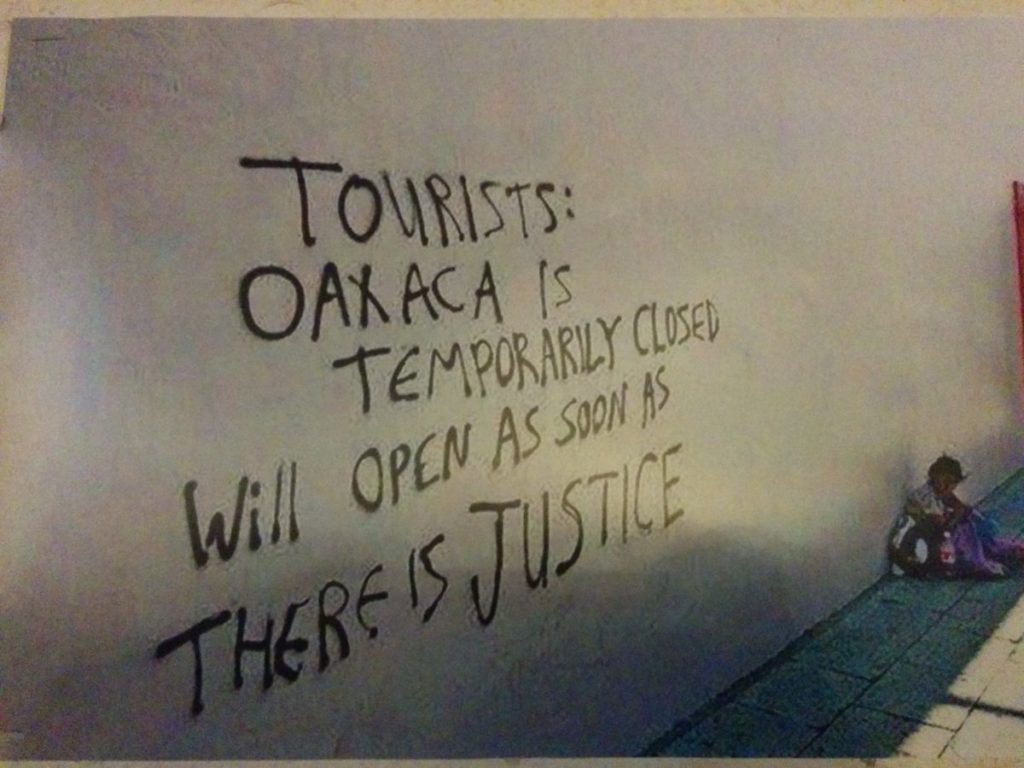

In 2016, when I visited, they were involved with the teacher movement that was organizing strikes, protests, roadblocks and occupation of the main city square against an educational reform that would disempower teachers. This moment invoked many stories about the 2006 popular takeover of the City of Oaxaca, that also started from a teacher’s movement and where Unitierra was also a very active participant. Directly participating and being rooted in social movements is one of Unitierra’s most notable characteristics.

An important step for Unitierra Oaxaca was to go to the adjacent rural communities. In San Bartolo Coyotepec, we visited a household that was a living museum of eco techniques and we learned about a process in which the entire community learned to stop burning trash, collect it separately in 16 types and sell it. The learning process was a mix of rules, citizen reporting, public displays, training for adults and children and empowering children to take responsibility.

In another village – San Pablo Huitzo – we saw the same process in an early stage where they had built the water cistern, the buildings and the dry toilets but they were just beginning to engage the community in adopting those solutions. When another community wanted to setup a local radio, I joined a team of three people that went to help. The team from Unitierra did not give a course about starting a community radio but they facilitated a process where the community found a name for the radio, brainstormed ideas for topics and organized work.

There are more UniTierras outside of Oaxaca, for example, one in Canada, in a chocolate factory. The one in San Cristobal de las Casas, in Chiapas, is an impressive one. Being the host of many gatherings called by the Zapatista movement, it could be seen as the university of the zapatistas. The mayans of the zapatista movement are engaged in an impressive project of building their autonomy by cultivating their own organic food, building their own schools and clinics and radio stations, rejecting any involvement with the “bad government” of Mexico and instead organizing in a bottom-up system of “good government”.

Both in Oaxaca City and in San Cristobal, the two Unitierras have a recurring event called “Conversatory – Roads of Autonomy Under The Storm”. It is a discussion open to the public around a “recompilation of informative notes, articles and analysis about social and political problems as well as struggles and resistances from towns and villages”. It is one of the few patterns that you can notice in Unitierra and it reinforces the commitment to learning by doing and directly engaging with life as a way to learn.

Gustavo Esteva was a good friend and collaborator of the “maverick social critic” of western institutions, Ivan Illich. Carrying forward Illich’s universe of thought, UniTierra rejects the idea of diplomas together with the corresponding ideas of professions and experts hidden behind them, claiming exclusive rights to manage learning, or health or justice for everybody else. They seem to go without even the most permissive structures that I saw in other places. Unitierra is the least structured of the places that I know to call themselves university. No curriculum, no application deadline, no induction, no yearly cycle, no journals or canvases to guide you, no residential camps. Just doing, informal conversation and some workshops and events organized along the way, as needed.

Unitierra is profoundly insightful and mind blowing in the way they reject artificial structures to let structure emerge out of natural human processes like doing, conversation, conviviality, friendship. The reflex of deinstitutionalization seems to have played in every aspect of the place, including the way Unitierra reached other places: through friendship. Unitierra beautifully embodies the idea of de-institutionalization while directly participating in social movements, placing itself at the heart of the action, catalyzing an emergent community learning process that they hope will “give birth of a new society in the womb of the old one”.

Action-Researching: Universidad del Medio Ambiente (Estado de Mexico, Mexico)

Universidad del Medio Ambiente (UMA) was founded in 2009 by Victoria Haro and Federico Llamas. The two co-founders were project evaluators in a socio-environmental investment fund in Mexico and the inspiration for creating UMA arose from the frustration with the low quality of the projects received. Nowadays UMA offers 8 socio-environmental master programs that blend online learning with seminars in its beautiful campus in Valle de Bravo.

UMA’s educational model has a strong emphasis on projects and is aimed at developing innovative professionals that can be change agents in their environments. One of the most inspiring descriptions I heard while I was there is “UMA is not an answer, it is a question”. UMA embodies this in its curriculum, inviting students to approach socio-environmental projects through the lens of “action-research” and critical thinking. They also embody this in the way they work as an organization.

One example is their inspiring campus. It blends into the surrounding natural landscape, it’s build out of mud bricks from the local soil, it’s only one floor, it has a green roof, a water filtering system and many other eco features. The way you feel in the campus speaks of UMA’s mission and character: connected with nature, with the sky, with the hills. As I was inquiring to know more about the campus, I was becoming aware that it was the result of a process that I found to be equally inspiring: the capacity to learn as an organization and to co-design with others. In the case of the campus, the co-design was lead by the brilliant architect Oscar Hagerman, with a team of people from UMA. As I understand, it was a highly participatory, iterative process that integrated a diverse scope of views -sometimes creating frustration for the constructors, eager to start.

I also witnessed first hand the capacity of UMA to learn and integrate new ideas when, only one month after they found out about the program for Self Directed Learning in the Alternative University, they decided to adapt and implement it in UMA with our help. In the same timeframe I saw them working to integrate the principles of the Oasis Game from Instituto Elos in Brazil. When they decided to start designing a bachelor’s degree, they found a creative way to bring a student from KaosPilot in Denmark for 6 months and a few other people for shorter periods from Alternative University in Romania or FabLab in Peru. The resulting design is a blend of elements from UMA, KaosPilot and Alternative University.

What these examples try to illustrate is an organizational capacity to learn through the action-research mindset, co-create and redesign itself with a voracity and aliveness that is uncommon at least for most schools and universities – if not for most organisations. The deep organizational instinct that I found UMA can offer the world is embodying in their existence the principle of designing your action as an experiment to learn from and being in the world more as a question than as an answer.

Open-Sourcing: Open Masters (California, USA)

I met Alan and Sarah – the two people at the heart of Open Masters – in Alan’s house in Berkeley, California. They were preparing to ship another batch of Wayfinding Kits to people all over the world. I offered to help and we had a sparkling and enthusiastic conversation as we were assembling the kits. Embedded in this moment is the character of the movement they are instigating.

Open Masters puts forth the idea that one person can “declare an open master”, design her own learning and find peers to share the journey. There is no need for anyone’s permission or invitation. There is no need for a diploma or you can give yourself one. Their invitation is open to individuals and groups and they offer only some simple but beautifully designed tools to help, like a deck of cards or a Wayfinder Journal or a set of principles. Their tools come with beautiful language and perspectives on learning, plenty of unexpected and useful ideas and a Creative Commons Licence.

One of their tools is a deck of Wayfinder Cards. They are organized in seasons. Winter is for reflecting and restoring. Spring is for planning and get going. Summer is for exploring and making. Each card suggests an activity and there are cards for individual activities and cards for group activities. In the Autumn deck for gatherings you would have cards like “Affirmation Party”, “Story Circle”, “Spectrogram”, “Partner Mentor Walks” or “Elephant in the Room”. If your group decides to play the “Affirmation Party” for example, everybody is invited to spend some time in silence writing down positive traits of each person in the room and ways in which they saw the other person grow. Then the music starts and people are free to wander around the room, showering each other with praise. In the end, in the circle, it is asked if anyone wants to share an affirmation they received that surprised them or that felt particularly special.

If this activity is not a fit for your group, you will surely find another one in the deck that works, and even if you don’t, after going through all of them you will be inspired enough to invent your own activity. Anyone that understands english could just use these tools to generate powerful self-directed learning and any group could use them to self-organize a collective support structure for individual learning journeys. A group armed with the wayfinder journals and the cards, could have enough ideas for a full year of rich and diverse learning.

Just as Open Masters does not have a headquarters (they sometimes work from Impact Hub Oakland) but they invite you into their home, the people-powered learning movement can happen in our houses, in parks or in public libraries. The powerful idea of Open Masters is the vision of open-source and minimalist designs that could be enough structure to spark a worldwide movement of people-powered, self-organized learning.

Isolating: Deep Springs College (California, USA)

Deep Springs College is actually a cattle ranch, isolated in a desert surrounded by mountains. Here, you will find 26 young people driving tractors, feeding the cattle or fixing the irrigation system. Working on the farm for four hours a day is one of the three pillars of this one-of-a-kind college. The second pillar is the academics and the third one is self governance. The students decide what teachers to invite to give classes, they select the next students that will attend the college and decide on most of the other aspects of their life there. When I visited, they were discussing whether to choose a drawing class or a broader visual arts class, they decided to limit their own internet access to 1 day a week and they decided to reject a re-design of the dormitory attic. Their decision making process was amazing to watch. Seeing this small college that recently celebrated a century of existence makes you wonder why student governed colleges can only be found in remote deserts.

The most powerful aspect that touched me was, what they call “the voice of the desert”. It is the transformative power of that desert that I felt right away when I entered the valley. I stopped the car and got out. It was magic. That place, maybe because of the quality of the silence, teleports you deep inside yourself. You can almost hear your soul breathing. I left that valley with a deep longing for being in the desert.

Deep Springs College is isolated on purpose so young people, right as they are preparing to become adults, can disconnect from the noise of the times and reconnect with the timeless rhythms of life. I think that one invaluable gift of Deep Springs College is its statement about the role that isolation in powerful natural places could play in our journey to finding our inner self and our life’s calling.

Designing & Building: Olin College of Engineering (Massachusetts, USA)

Olin is a giant makerspace with a flexible engineering curriculum, a design thinking approach, a focus on project-based learning and a broader view of an engineer’s role. It is a university that does no research so it can hire teachers that are fully interested in teaching. Even their few required classes are also set up as flexible frameworks.

For example, in one of their first design courses out of many, you design a toy and a play experience for 4th graders. The play experience is assessed by 4th graders. You learn math and physics by building a boat. In another course the teams interview a group of people like “urban shamans” or “garbage collectors”, come up with insights, do a collaborative design process with them and present to them a final design that should be useful. In the “Engineering for Humanity” course they begin with understanding the needs of vulnerable clients, like senior citizens, and end up with “implemented, adaptable, adoptable, and sustainable solutions”.

The biggest team project is a nine months course where some teams choose an actual brief from a company and others choose an “affordable design” path and tackle a social problem. One of the students was excited that: “for the first time I was doing something from nothing“.

The students mention that aside from the engineering and design aspects, “you have to put thought and care into the team experience“. The students need to take one humanity class of their choice per semester and through their tight partnership with Babson and Wellesley colleges they can also take courses there. Students from the other colleges can also join Olin teams. “I don’t remember a single team project without a student from Babson” said one of my student guides.

Aside from the flexibility to choose most of your courses, Olin also encourages students to pursue their own passions and they can even get up to $150 for pursuing a personal interest. They can also take a break for one semester. Self designed majors are possible, there is a 4 credit self study each semester and in entrepreneurship class you can work on an idea of your own. Then there is the Iterate Course that can be taken multiple times and is “a quick to credit course where students can attack a problem“. Students appreciate that there are many options for self-designing your own path and pursuing an interest. The general approach and purpose of Olin’s flexibility is to “encourage breadth until you find something to go deep into”.

There is also significant participation of students in determining aspects of their common spaces and taking care of machines. There are NINJAs (=”need information just ask”) students that know how to operate a particular machine. Some of the furniture of the college is designed by students, the Library was designed by students and when I was there they were preparing to redesign the Machine Shop. Their relationship with the physical space of the university was expressed by a student who said that “we have the privilege to own our space, organize it, leave our things“. I also heard about student taught classes.

For me, Olin College represents the exciting idea of a university as a makerspace where one’s (engineering) higher education is essentially a self designed series of interesting, challenging and creative team projects where you gradually design and build more complex and more relevant things.

Playing: X-Lab (Sao Paulo, Brazil)

X-Lab is a game that challenges children and teenagers to one general mission: change the world by playing. As much as I could understand its approach to gamification, it focuses less on game mechanics like points and badges, and more on storytelling as well as on reframing reality as a game and yourself as a hero that has what it takes (the X) to change the world. The chosen hero receives the first challenge to form a team, the second one to create the X profiles of the team, then to create a facebook page, post the profiles and gather the first 50 followers and the game goes on. Each challenge is validated by a Game Master that offers the next one.

X-Lab does not present itself as a university, an ecoversity or any kind of alternative to universities and this is precisely how it is relevant to the conversation about transforming higher education. What if, as a rite of passage from childhood to adulthood, in order to find your path into the world and prepare for the journey, you don’t go to a place called university but you play and complete a mission with your team, in a collaborative game? X-Lab is right now activating hundreds of young people in taking care of the environment and engaging with social issues. They could continue this playful path as they prepare to become adults and full participants in their communities and in the world.

Reflections on the larger movement

COMMON CHALLENGES

While amazing and fascinating in some aspects, every one of these places has challenges. Even more questions come up as one thinks about the possibility for each model to spread. For example, some of them depend on one or a few highly gifted and committed founders and others depend on fortunes being invested in their existence. One way or another, they depend on scarce resources.

Some of the projects have the challenge of being too small and fighting for survival. This means that the few people they have in their core-teams can take little or no energy away from what is critical to survival for investing in some generative projects like designing open-source tools, sharing their practices and their stories with the world, hosting visitors, writing down their ideas and their learnings or visiting other places to learn more and integrate and contributing to the wider movement.

The ones that are radical in their worldview find it hard to attract material resources to properly flourish. For the universities that do not offer degrees, for example, getting the resources to operate is especially difficult. Being such intense and under-resourced endeavours, their capacity to explore out of their context and connect with likeminded projects is limited. Also, their stories are less popular than their epicness would deserve. They have a treasure to give to the world but a capacity to do so that does not match the treasure. Also, I would say that in some cases, the genius is obscured by mundane challenges because the organization lacks some critical skills or resources.

EVOLUTION

There are three things that I would bet on to evolve and deepen these projects and this larger movement of radically reimagining and re-inventing universities:

Extended Learning Journeys

It might be obvious for me to say that, but I’ll emphasize it: extended (one year or more) learning journeys for key people in the movement would greatly nurture the core of the movement. This can’t be overrated.

From my experience, three things might happen:

(1) You come back stronger as a human being, with your purpose uncluttered and your motivation refreshed.

(2) As a learning designer/facilitator, you discover different logics and lots of ideas that make you more flexible and creative. You see some elegant new approaches to your old problems. You have some valuable relationships that you can draw inspiration from and build partnerships. And you just saw your project in a new mirror, so you fall back in love with its essence.

(3) Your project just had the chance to be without you. Some people will flourish. New things are tried. And your unique role becomes more clear to you and to others when you come back.

If the extended version is not possible, I think that a learning journey of any duration will be highly fertile. In general, I think the movement of people (from students to founders) between these radical experiments would greatly enrich the ecosystem.

Open Source Documentation and Tools

For growing and deepening the movement, It would be useful for us to have a systematic process of documenting and open-sourcing the learning architectures and various designs of these places, maybe using a model similar to hundred.org. It could also take the form of “Starting A People’s University Guide” or online course. Also, there are tools that can be built that could help in organizing such places more efficiently, freeing resources for other activities. Also, helping their capacity to host people and to share what they learned could greatly deepen each project with each other’s insight and cross pollination.

Storytelling

These places have powerful stories to tell. Having this collection of radical models and experiments more visible through stories of their students and other members of their communities would inspire many people. I think there is a critical role of radical models in stimulating the cultural imagination of the world so there is a stake in making this movement more visible and to inspire more people to join the radical living experiment of reinventing universities.

Conclusions and my journey forward

Being a student, even for a brief moment, of some of the most radical and amazing universities of the world left me with a lot to integrate into my life back home. As I returned to Bucharest after 636 days and 112,000 km, I aimed to be a revolutionary in my own daily life. I decided that the last thing I throw away would be my garbage bin and I adopted a zero-waste lifestyle. I hardly buy anything that is packaged, I make my own toothpaste, deodorant and laundry detergent. I cook and I compost. I have only the clothes that can fit into a backpack and I have an ongoing project to reduce everything that I own to less than 200 objects. I spend five times less than before. I installed a GNU/Linux operating System, as a first step toward a commitment to free software. I plan to move to a village.

These concrete changes are only the tip of the iceberg. My worldview and my emotional landscape have shifted and I find myself enjoying life more, having deeper connections and having the courage to take bigger social risks for the sake of walking my own path. Finally, I feel that I’m being the change more than I work for it or talk about it.

I reshaped my relationship with the Alternative University. I see myself as a student now. The whole organization is radically transforming: we dissolved the old organizing structure and 93 former students and staff co-founded the Alter/natives tribe – a cooperative that will nurture The Alternative University for the next 10 years but will also start other enterprises that express our core values of freedom, kindness, courage, play and learning-like-crazy.

As for my journey forward, the ecoversities journey refreshed my commitment to the overall movement of radical reinvention of universities with the particular focus of instigating a worldwide web of local multiversities that are self-governed and self-organized by their own learners. As one can anticipate that far, you will find me tinkering at this dream for the next 7 years.