by Rowan Salim

In 2016 I spent 5 months as a guest at Shikshantar in Udaipur, one of the campuses of Universidad Swaraj in India. Shikshantar was made up of a motley crew of walkouts and dreamers unearthing and experimenting with vernacular learning technologies, ancestral, earth bound ways of knowing. It is based in a bungalow on an urban street lined with mango stalls and holds an open door policy. There is a garden, a library, games, musical instruments, a growing collection of curious tools, computers and a lively kitchen. They hold a community party every Saturday called Hulchul Cafe where people cook and play music and put on performances, talk and tell stories and everyone is welcome. The walls are covered in artwork and posters with inspirational slogans and photographs of various initiatives. One poster caught my attention.

Cycle Yatra!

Join us for 10 days cycling around Rajasthan

with no money, no mobile phones and no ID cards

The date of the event had passed. So I asked my new friends about it.

“Areh Yaar, it was the best!”

“People are so generous, they let us sleep on their terrace and gave us rotis and dal and we told each other stories and sang songs and we helped them in the fields.”

I met more and more people who had been on cycle yatras and pad yatras, cycling or walking with no money or mobile phones. Yatras, or pilgrimages, are a powerful ancient unlearning pedagogy used at Swaraj University. Cycle yatra was inspired by Satish Kumar’s four year 1960s walking journey from India to the four nuclear capitals of the world with no money and with a message of nuclear disarmament and peace. Everyone I met who went on one of these yatras was full of stories full of love, learning and adventure. They may not have had any items in their pockets, but they all seemed to carry with them something a lot more valuable and helpful. A sense of trust. Trust in the world, in themselves and in the people they meet. Like someone had switched the magnet off.

I returned to London in the days after Brexit, when England was at once angry, jubilant, divided and sad. Perhaps, I thought, people can rock up to a village in India and expect to receive hospitality, but you’d be bonkers to do it in England. And as the weeks passed, I started wondering, was there not something universal about hospitality? About curiosity to the strange?

I had grown up in Morocco, Yemen and spent time in the Levant, and knew in my bones the power of hospitality. Hospitality, it had sometimes felt to me, was more like a generative and joyful survival strategy than a luxury. The last 9 years have been a journey searching for it in England and in the human spirit; and leaning, full body into the simple power of just walking.

So one afternoon in Autumn 2016, I sat in my flat in South London and created a facebook event. Walk to Wiltshire. 100 miles, no money and no mobile phones. I invited my London friends. Three responded positively: Zoe, Jan and Awais. This would be the first of three, the rhythm of time meant that it just so happened that I was ready for a new one every three years. This year is due the next one, and this article is a sharing of experiences so far, and an invitation.

First pilgrimage: Walk to Wiltshire - October 2016

You can read a full account of this journey aquí, and listen to a podcast about it aquí.

The first pilgrimage was raw. We didn’t know much, and we simply walked out of my flat. We took the two rules seriously. No mobiles and no money. We don’t carry ID cards in England so not having them didn’t matter.

For this pilgrimage, apart from one night with a friend in Salisbury plains, and our final destination, a place of friendship, the cottage home of my friends Naomi and Ben, we didn’t plan where we would stay for the other 7 nights, and this emerged to be one of the defining features of our experience.

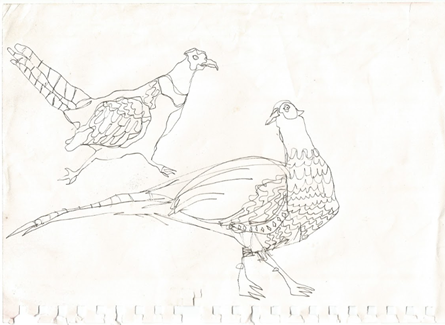

Food was easy to get by. Jan was an experienced dumpster diver, and wherever we went we found perfectly good food being thrown out, and all we had to do was learn to find it. The UK throws away 9.8 million tonnes of food per year – no one should ever go hungry. But more so when we did interact with people around food, there was an ease and comfort with which they shared it. Here is a small anecdote from the account:

It is like the invitation to practice generosity, in a safe and contained way, is a much sought after gift. Something happens to the soul when we give, and so we are drawn to it. My friend Ajahn Santamano is a monk who fasts most of the day. He cannot get food for himself and can only consume food he has been given between dawn and noon. He describes this daily practice as an opportunity for relationality and to practice generosity and one which in his experience, people are glad to participate in.

The lack of secure abode, while travelling in autumn as the cold sets in, was harder. People generally were not as forthcoming! And this meant that a large chunk of our days were spent honing in on our survival instincts. From the afternoon onwards, our senses were sharpened to connect with people for this purpose or find a den to sleep in. The way that we looked at the landscape around us, and the way that we approached strangers, was directly related to a need for help, to find shelter. This shaped the nature of our interactions.

By and large people were curious. They were approachable, they listened, they took in what they saw and a part of their souls lent in. Though there was a moment which occurred time and time again, so that it seemed to want to be named. It was a moment of awareness, a moment which called for a decision, for growth. Call it an aplastic gap. Aplastic being the condition in biology of not being able to exhibit growth or change in structure. It was a moment trapped between different choice sets of values. It went like this: You meet a couple of strangers. You have an encounter, hear who they are and share your journey. They are curious. Something inside them gets awakened and there’s a craving for more which is read in the tones of their features. And then you share that you are looking for somewhere to stay. And over their curiosity, and their nestled values of trust, hospitality and generosity, looms a bigger and greater value, that of fear. Suddenly you see, across their eyes, like flashes of rockets and bombs landing in their inner landscape, headlines of insurance and liability, murder. And that second set of fears, in the short moment of the encounter, overrides any ability to engage with the possibility of growth and relationality. And so the encounter, time and time again, ends with a “Good luck! Yeah, just follow the path down and you’ll get to the next village, maybe you’ll find something there.” An aplastic gap – an inability, driven by fear, of leaning into a moment of growth.

The other thing I noticed was that even though I was also curious during those encounters, my own curiosity was likewise overrun by my need for shelter. And so, many opportunities for deeper delving into place and relationship were stagnated. Instead I did learn a lot about my own resilience and our capacity to be together as a group of 4 pilgrims and with creativity and trust, find solutions. This pilgrimage was a gift for my ability to survive. I was never a very scared person, but after this, the edge was taken off my fear of the unknown, and my trust in myself, in the land, in the power of relationality, and in what may emerge to meet a moment, grew. Because in reality, despite the obstructed twilight encounters, every night we had was grand and full of learning and interaction. We were hosted by beautiful people who emerged out of nowhere full of trust, hope and curiosity, and when we had no hosts, we found shelter in the most unexpected of places.

With time, I also noticed that once accommodation was secured, or once trust was built ahead of needing to ask for accommodation, the desire and ability of people to be hospitable was enhanced. It might simply be that people needed more time. Ajahn Santamano, in his practice, says that having boundaries within which generosity takes place can help people lean into it. For example, the fact that he can receive food only in the morning, makes it easier for people to give it. With a loss of lived customs of hospitality, there is a need to frame interactions for them to be palatable, until new customs are shaped and old ones rebirthed.

It is like hospitality sits in every human body, but for some people, individuals, cultures, it sits on the surface of the skin ready to pounce, and for others, it has lodged itself deep in the marrow.

In the summer of 2003 I did some research around Nahr Al Kabeer, Al Kabeer River, which forms the northern border of Lebanon with Syria. I spent a day driving with my host, Hani Daraghmeh, along the borderlands in Akkar province looking for a community to host me for the summer. As we approached the end of the day we found ourselves in a meander of the river known as Al Baqaa. Soon we were seated around an outdoor family restaurant table in the dappled sun, by a flowing tributary with children jumping into the water off a bridge, and our hosts, Spiro and his family, laid out without request, mezzes followed by grilled meats for us with joy. We came to pay and all forms of payment were strictly and adamantly refused. I would go on to spend 2 months of the summer with them, playing with the children and crossing the river in and out of Syria learning stories of this permeable and fluid boundary.

Many years later I found out that on a visit to see me there, my mom had taken Spiro aside and with her air of diplomatic proficiency, set out to settle the score. What do you want me to pay you for hosting my daughter, she had asked. There are costs and she can’t just stay for free. Nothing he responded. We’re happy to have her here, he said, with the shrieks of water play echoing through the trees behind them. My mother insisted.

So Spiro asked her for her wallet, which she took out and handed to him. It had a wad of notes inside. He looked at her and took all the money out.

Spiro thumbed through the pack of notes, and from one end peeled away a single 10,000 Lira note. The equivalent at that time of $4. He separated it from the pack, put the rest in the wallet, and handed it back to her. That can’t be it, she said.

So he then asked her if she had a pen. She rummaged in her handbag, found one and handed it over. He put it behind his ear.

That’s my payment he said. Thank you.

The next 2 months would be an olive oil infused mujaawara, both for me, and for Spriro’s family who hosted me, and their extended kin of family and neighbours. Mujaawara is the term elder Munir Fasheh uses to describe the innate process of learning through relationship and proximity. And so, from afternoons stuffing stuffed aubergines into oil filled jars on the terrace with the women, giggling children in our wake, to sunset kezdouras, leisurely walks, with Spriro’s teenage children, Samira and Sa’er, learning about each other’s worlds, the learning, growth and joy of each other’s company was dancing, trustingly along the lines of mutuality – so that any payment, I expect Spiro thought, would spin the relationship out of balance.

Elsewhere, in Iraq, where my family comes from, the whole of the south of the country transforms into a hospitality bonanza, as pilgrim routes for hundreds of miles become lined during the Arba’een period with Husseiniyas to host the millions of pilgrims who walk to Kerbala and Najaf. My maternal second cousins who live in the town of Souq al Shioukh, await this season with joyful anticipation, knowing that they’ll be cooking and offering abode to the masses for weeks, and the sensorial learning journey that that offers them as hosts.

In England, traditions of almshouses, churches as sanctuaries or simple traditions which have now become performative like putting a candle in the window at Christmas so that lost souls may know they will be welcomed, evolved for a reason, and are testimony to the existence of hospitality in these islands’ marrow. At a time when Britain was seething with anti migrant sentiment, and flimsy boats were sinking in the channel, it felt like a quest for these flickering lights was necessary.

Second pilgrimage: Sandling to Canterbury - July 2019

Oh what a glorious time this was!

The second pilgrimage I did with my friend Dan, whom I had met through my work with the Freedom to Learn Network, who had been searching into the idea of rewilding education and wild pedagogies. Pilgrimage had come up in conversation and soon we were on a call planning one.

Early in the conversation, Dan had a proposition: how about he doing some research and contacting places along our route who may be open to hosting us.

The schooled part of me resisted. There were rules! We can’t just break them! But the deschooled part of me knew that rules are there to be broken, plus, what rule was it anyway that forbade that from happening? That was my own fabrication. And surely what’s more important is that pilgrims can design their own journey in a way that feels good.

So Dan did the research, and I requested that we keep at least one night without planned accommodation.

The result was incredible. Suddenly the walk went from being one of endurance and trust and resilience and creativity, and spun like a sycamore seed into a spiritual space. Walking along the land, without the stress of finding shelter, the encounters we had were slow and deep and we were able to linger in the relationships and the places. I was eased into a spiritual realm through the walk and the company and I am ever grateful.

Here it felt that we were guests of the land. We were not simply passing through. We were able to stop more, to linger, to notice and be noticed. And just as previously we’d had conversations with people, tuning in to how they were receiving us, here, under a beech tree, in a chamomile field, we were more able to notice the signs of the land and the spirit of the places acknowledging and welcoming us. There are stories to be told, but some stories can only be told in person. Here is a poem from Dan, written upon our return:

Signs

The body of the Blue Jay,

later, its feather.

Three crows ahead, on the path.

The insistent alarm of the wren.

Two staffs, one branch.

A carpet of camomile.

The language of the desert, unexpectedly shared.

The company of a Djinn.

Small moments, amplified,

To us, sensitised to significance.

Tenderised on the path,

in the flow of all things.

There was more space for noticing.

Our time with our guests was immediately leisurely. Leisure sometimes gets a bad rap, but it captures what you might choose to do in your free time. And when free time brings together souls who haven’t met each other before, brought together for a moment of intersection, of pollination, of eddies, the learning can only be as glorious as a murmuration of starlings.

Two of our hosts, Lizzie and John, were the wardens of a garden, a sanctuary, called the Quiet View. Through the summer blossom you walk and meander until you reach a labyrinth, drawn in the earth with stones. A labyrinth is a path that spirals and turns round to a central point. It is an ancient spiritual tool, found in all corners of the world. As Lizzie describes it, ‘it transcends all cultural and religious boundaries and can be calming, enlightening or healing’. We learnt of the journey, to release, receive and return. For times when a long walk is not possible, the labyrinth provides a local, mini walking journey.Through providing a walking path, a certainty to reach a destination, and a clear return route, they provide the journey space for a spiritual, inner enquiry, which many are drawn to pilgrimages for. It’s learning that is internal, free of the encounters along the way, apart from those with self. Though, bring a group of children to a labyrinth and you’ll have encounters galore! There is a map of labyrinths around the world that you can explore and it’s also easy to make one with sticks or lines drawn in the sand, or even use your finger to trace one on a parchment.

We also became more aware of the path itself. Noticing when paths were used, when they were overgrown, when we could see evidence of them being maintained, signposted. The number of public footpaths in Britain has been in steep decline as the sharp claws of private ownership swallows ancestral ways, and there are movements of people, walkers, ramblers, around the country walking to claim them and keep them within the public realm.

Here is another poem and words from Dan, written upon our return:

Wayfaring

How beautiful

that You went ahead

and left a sign

for those that tread these paths

are blind

to the possibility

of being lost.

Thank you, for all those that give of themselves and that have to us on the journey. To keep the way open, to keep the path signposted. That it is enough to glimpse the way when you are uncertain, when the path, and the canopy, and the green, all look alike, and there is a moment of feeling lost, of losing the way, and yet it seems it is also about an older way of knowing, and of being guided, of being taken care of.

My heart was enlarged by the men and women who move through the woodlands and over the fields, with old maps in one hand and wood and tools in the other, to maintain the way, to not allow the way to become overgrown, for the waymarkers to remain clear, to keep the way open.

In part this has to do with familiarity. When we walk near to where we live, near to home, where everything is known and recognised, we do not need maps and signs, directions and signposts. But when we are far from home, not lost but uncertain, unclear, hesitant, unsure which way to turn, which path to follow, which fork in the road to take, it is then that we sigh in relief, when we glimpse a marker, a sign, that brings the journey into focus, that gives us back our bearings. I thought of God, of a someone going ahead, knowing the way. Not that there is only one direction or route, but that there are ways of staying found, and it was this feeling found that we loved, that we did not have to fall into fear through being disoriented, or through feeling lost, wondering, worrying about where we were or where we were going, or how we would find our way, about the obstacles we would face and the kind of help we would find. We felt a peace, a restful sense of being supported, that it would all work, that we were being held.

Third pilgrimage: Devon and the map of hosts - July 2022

Three years later, I had found a wider community of practitioners exploring what it would mean to rewild education, and so, talk of walking and pilgrimage was alive, and a few were keen to try this out.

We were drawn to the west country, and specifically Devon, which over the last few years has emerged as a spiritual, cultural and ecologically minded hub of connection and creativity within these isles. We revisited the question of accommodation and hosting and decided to write an open letter to our friends and networks in Devon and invite people to add themselves to a map of hosts.

In this iteration, we didn’t have a set destination, but rather, designed a circular journey which would take us around to visit some of our forthcoming hosts and return with a warm welcome to our start point, the old stone walled home of our dear friend Laurie in Totnes. Again, we decided to keep one day without a confirmed abode so that we may be guests of the land – the ever generous host.

A new consideration for me on this pilgrimage was the invitation from my fellow pilgrims, Max, and Marina, to tune in to our intentions for the pilgrimage at the threshold of setting out. This initially felt like an intrusion to me! For me, pilgrimage had felt like a full hearted surrender into emergence, into the unknown – and pre-determining intentions felt like channelising a meandering brook! And yet the invitation was there. For this time, I settled with an intention to be with emergence – and yet the power of intention, and how it interplays with the openness for emergence has become a curious theme in my work and explorations. I have come to learn of the power of it in its fullness, the ecstasy of surrendering without it, and the skill of holding it lightly so it may shape journeys and yet, like a healthy river, break the bank if need be.

There were many moments of beauty in this pilgrimage. I remember the moment, with Marina and Max on either side, noticing the steady tri-rhythm of our footsteps, our heart and our breath. A grounding tethering of body, spirit and place – all the better with friends by our side, feeling the same things.

On this pilgrimage I was also moved by the clarity with which it became apparent that the host/guest relationship is one of mutual benefit, learning, growth, and joy. Something I had felt in previous mujawaraht, but now sang its own virtues.

After three days of walking up to Schumacher College, where tea and toast was plenty, jumping the fence into Martin Crawford’s food forest, being hosted on loved and cared for lands and swimming in crystal waters, moving piles of logs for our hosts and eating soup and buttered crusty bread, then sleeping out on Dartmoor, quenched by kin’s deep waters and feathered by its gorse, we made our way back down to an area called Diptford where we’d be hosted by a family who had just moved to a new home on Barn Hill where they were looking to set up a learning community. Tallis, Lloyd and Amity had been in their home for a few weeks and had not had a moment to stop and breathe. Our arrival, alongside our combined experience of working within alternative education settings, and the spirit of gift and exchange led to an evening and a day replete with gifts in the form of conversations, shared food, local exploits and deep water swims, play, a yurt and a woods, dreams, deep cleaning extractor fans and a pair of bejewelled labradorites. In that moment, the learning exchange, and the giving and taking in the encounter felt like it had struck a sacred balance and came at just the right moment for all involved. From then on, that relationship, between host and guest would take on a different meaning for me, where the hope, desperation, fear and values discord, the aplastic gap, encountered in the first pilgrimage, would transform into an oxygenated trove of mutuality, comfort and learning.

In writing this piece, I reached out to Lloyd to invite a remembering of how they experienced our visit, and he sent back these words:

At the time of Rowan and Max’s visit, it was a wonderfully warm and hazy summer. My family had just arrived at the property a few months before and the land was vast and untouched. Turning a dream into reality can be daunting and exciting at the same time, emotions and what directions to take can be a whirlwind, however, there was something very grounding from their visit. Like guardian angels they bridged the gap between the project on the ground to a wider movement that I wanted to be part of. It felt very encouraging that they considered Barn Hill a place of interest and confirmation that I was pursuing something of value to myself and the wider community.

As well as providing encouragement towards the project, Rowan and Max contributed towards a warm felt atmosphere within the house, not only helping improve the condition of the house that we had not been in very long, but towards conversation and discussion that our daughter too loved and appreciated. Those two days are still firmly etched in my memory and still arise in every day chatter, for that alone we are eternally grateful for their visit.

A moment to look around

There is a growing grassroots network of individuals and groups in the UK looking at pilgrimage, walking, hosting, and being free on the land who are doing incredibly beautiful and important work to liberate the marrow of hospitality from our bones. In particular the Right to Roam movement and the Stars are for Everyone who are campaigning for the right to access the British countryside as well as the right to sleep under the stars – a campaign which is fighting the tentacluar arms of capitalist law with trust and trespass. These are supported by ever more singers and storytellers who, through rambles, fireside gatherings and instagram posts are telling the history of land rights so that we may remember that we can shape it.

There are also individuals and groupings searching into the history and traditions of wayfaring, and carving out relationships along the way which may help the blood flow through old arteries. Of note is Will Parsons from Wayfairing Britain and the work he has done to build relationships with churches as sanctuaries and Nancy Powell from Etheria Pilgrims who after a childhood of going for family walks and bringing her friend along, noticed the joys, connection, curiosity and capacity to learn through walking. There was also a moment of insight that we live on this land and we can get to know it and love it. That we don’t need to seek satisfaction elsewhere, warmer, more splendid. At 18 she simply started walking with friends and self styling pilgrimages of the heart.

There are also black, brown, women, queer, Muslim and other movements, fully aware that the history of these islands has meant that there are layers to the disconnect and that some people’s connection to the land has been severed so astutely or never allowed to take root at all. Severed so much and filled with so many layers of control that we have forgotten that we can walk, that we can love the land and that the land can love us back. This is being healed, and that work is joyful, beautiful and full of feeling. Part of this is inviting tuning into how we practiced walking in our ancestral lands, so that we may let the blood flow from our marrows, and give red fuel to our step.

This has led me to further inquire into what pilgrimage and walking in particular look like in the lands I come from. We have a whole treasure trove of traditions of walking and hosting, some of which are explicitly about learning and connection.

My friend Saleh Abu Shamallah describes masaars in Palestine as organised walks that pause along a route. There will be an initial meeting place and an end destination, but the walk itself is the event and along the route, you see the features of the land, you meet the people who live there and hear stories of the ancestors, you eat from the land and drink the water, listen to the birds and joke with your friends in locations with memories.

Masaars can be organised by associations or individuals, a local person who tells the history of a local area, or they just happen because they exist. For example, you might join a shepherd along her route and help tend to the goats, hear her stories and pick the herbs.

Saleh describes a masaar happening when there’s a ‘3ilaqat hub bein shakhs wa masaar’, علاقة حب بين شخص و مسار ; a love relationship between a person and a route, as well as an unacknowledged awareness that “everything you know, know that there is someone who will want to know it,” or that the celebration of the place, the honouring of the story, the knowledge, comes from sharing it.

Deep within the vernacular technology of what a learning journey, pad-yatra, masaar offers is the very action of walking, the path that you walk and the encounters that you have. The destination that the word pilgrimage so readily glorifies, I’ve noticed, is in some ways by the by.

Walking, or moving away from what we know to what we don’t know, is one of our earliest ever learning technologies, both within the age of humanity, and the age of a person. A baby will be held close to the warmth, comfort and knowing of their parent’s bosom, and then as soon as they are able to, they will want to go ‘there’. There is what they don’t know and what they want to learn about. And so, they learn to crawl and learn to walk so that they may go there.

Within human scale time, we lived in groups, villages, communities on lands that we knew and conglomerations which we understood. But as soon as we needed to learn more, we walked to new places. Of course some of these were pilgrimages, but some were also purely learning journeys, exploratory, in self and outside of self.

On the flip side of that, living in a village, if a traveller came by, then we knew to welcome them. Because they would bring news and stories of the world, and it is with that that our knowledge, understanding and wisdom grew, and hence hospitality became an instinct.

When I lived in the northern mountains of Hajjah district in Yemen in 2005, there was a saying that the inhabitants of the 7 mountain ranges around you are your friends. The family who hosted me invariably had travellers stay in their mafraj, or what we would call in Iraq, the diwan. I remember, on one occasion, a lone female traveller being hosted in the women’s quarters.

My friend Nariman Mustapha also speaks of oudhat al musafireen, اوضة المسافرين, the traveller’s room often seen in homes in Egypt, and especially common in the Nubian South, whereby every home will traditionally have a travellers’ room. A room on the edge of a house, with its own entrance, and a key hanging on the outside wall. Any traveller can let themselves in, moving the key indoors, by which the hosts know it’s occupied. For the first three days they provide food and water and do not require engagement if not desired from the traveller. Only upon the third day, does an exchange ensue.

Fourth Pilgrimage: Summer 2025

It’s been three years since the last pilgrimage, and the tripartite tethering is calling me.

I’m not sure yet what it is going to look like, but gosh am I excited! There are a few friends and acquaintances now who are keen to try this out, either as guests or as hosts.

I feel like the evolution of the map of hosts has been a pretty cool thing. I’m not techy – so get in touch if you’d like to help spruce it up, but I feel like it could be an incredible resource to support people to map their masaars, their pathways. So here is the invitation: add yourself to it! I feel like once you identify where you want to walk, you could do a call out in that area and invite people to add themselves. The way the map currently works is pretty open. You add the information that you’re happy to share, and either provide details of your home so that people can just show up, or provide a rough location and contact details for people to reach out to you. It could grow in patches as each new person or group exploring this form of pilgrimage can use it to invite hosts. The wealth of knowledge and wisdom and connection could be a real gift to our learning ecosystems. I am also aware that there remains something beautiful about serendipitous encounters, and want to protect that possibility as well. The aplastic gap, with time and choice, can also be healed.

I’ve also had a lot more practice bivvying. Bivvying is the liberating practice of sleeping out in a sleeping bag covered in an extra waterproof and breathable bivouac bag. The discovery of this has revolutionised my access. I recommend it. It means that your route can meander, you can spend nights being a guest of the wild, and you can have longer distances between hosts.

I still love the idea of walking without money or mobile phones. I think it adds so much. Our modern society has gotten us so used to the security blanket that these two commodities offer – and in much of life, that is a blessing. But somehow it feels like the absence of them helps us unearth more innate and relational powers. Human powers of survival, of ingenuity, of noticing and of connection the depths of which we can be quite unfamiliar with. It helps us notice our own and others’ gifts, which can be obscured by how easy and shiny these two commodities are. This spurs us into a journey of unlearning and an opening of new possibilities. In this transition, something seems to happen to our perception of fear – an unlearning of the stories of fear which hold us captive, and in doing so, a release into trust and the unfurling of emergence. It is this trust that my friends in Udaipur sang about, and which I am celebrating and singing on about here.

The thing about money is that it becomes the default gift. When you don’t know what else to give, money will do the trick. But the learning journey is an invitation to engage with the other, to tune in to what may be desired, and to tune in to what gifts you have to meet that desire. It involves listening, and being present to yourself and to the other. At its apex, when the moment shows up where the expression of hospitality and gratitude wants to be expressed, it is through that relationship of gift and desire finding each other, that exchange and mutual learning happens. This moment can be ecstatic. And it can take any gazillion of shapes. Money is helpful, but it’s just one shape. And the story it tells is kind of known, and kind of boring. Gift exchange happens throughout encounters, through being present, and its expression can dive deep into our beings, doing loop-the-loops in our souls and soaring, as we search for meaning, connection and understanding.

And yet, the surrender of these items is an invitation, and each at their own discretion. I’ve learnt that holding on to rigid rules isn’t so much fun. Nevertheless, these are valuable options.

So far all of my pilgrimages have been with adults. However, pilgrimages would be incredible to do with younger people or for young people to do by themselves. I’d really like to explore this. I’m also aware that within the UK youth landscape, there is a deeply routed and bureaucratised sense of fear which manifests in a need to safeguard. I’m curious about how to name this, understand how to take due diligence, whilst also being open, enabling and liberating.

I’m curiously cautious about the role of the gatekeeper, permission giver, guide. There was a project in Belgium which took young offenders on a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela, and if they made it to their destination they got early release from custody, with the understanding that the learning and growth they will have experienced would forge them changed beings. But the project had a caveat, that the adults who join the young people only take part once. They are just as new to it as the young people they join. Somehow, within pilgrimage, it’s the journey of the self, the trust in the unknown, and the mutual learning which holds the magic within it. The guide is the path and the journey, and your relationship is with it, rather than the teacher alongside. For as long as we’ve lived, we’ve been able to pack a little bag and walk. People can make incredible guides, many masaars have guides as part and parcel of a path, because they are part of the path. Masaar guides are hosts along a stretch, operating within a gift culture born by love. But many modern pilgrimages are sold as packages with guides who take care of all the logistics, and there are livelihoods associated with that; or where the liability for the journey rests outside of the body of the walker and within another body. Somehow that shifts things. Perhaps not needing to concern oneself with logistics and exchanges opens up room for a more spiritually tuned, inner pilgrimage. That is something I’m curious to understand more. But central to walking as a vernacular learning technology is its simplicity, and its accessibility. Open the door, and walk out.

A note on friendship. There is an article I really appreciate called Friendship is a Route to Freedom. It in sum explores how freedom was once inseparable from interdependence, close ties and kinship. When travelling with others, you have time alone, in communion with the land, and in different constellations with each other, finding a balance that works. Reciprocity and relationality, soaring and doing loop the loops, and learning together, happens all along the way when travellers journey together. We are in a dance of supporting each other and convening together. In learning how to be in kinship, in sharing mujaawarah, the reliance on each other, the exchanges and the slow chew of the encounters form soil rich for growth and love. Friendship is a gift of journeying together, and one through which trust and liberation can be found.

I was lucky on the 8th of October 2024 to encounter my own wandering traveller and be invited to host him. He was a young Irish/Canadian man, travelling on a magical bike which he had designed with his friend, across many lands and countries. I stumbled upon him outside the high court of justice as the Right to Roam movement was awaiting the high court’s response to an appeal about the right to sleep under the stars on Dartmoor. Curiosity was followed by conversation, then were sandwiches, and soon, my own plans for the day were gloriously thwarted as we journeyed across London to visit the Community Camp for Palestine outside the American embassy, then made it home for a meal and slept out in the local woods. The following day I took him to the community garden where my neighbourhood kids were mesmerised by the handmade travelling machine and its intoxicating musical instruments. These encounters are the things of dreams, and yet they’re so possible.

Pilgrimages, pad-yatras, walking journeys, masaars, and all the names of these journeys from around the world, from your lands, from your grandmothers and grandfathers, are sublime tools for learning. What fuels them is a set of very human qualities, deeply rooted in our bodies, from our footsteps, to our heartbeat, to our breath. They are amongst others, hospitality, generosity, curiosity to the strange, gift culture, gratitude. The qualities these in turn give birth to are children to mighty trees. They are, amongst others, resilience, self knowledge, learnedness, being a good friend, a capacity for connection, for care and for growth.

Like play and story, walking journeys are a vernacular learning technology. We can read books, go to workshops, and attend lectures, and we will learn; and let’s also remember that our bodies; our tongues, eyes, backs, brains, tummies, toes, are hardwired to learn in certain ways, and allow ourselves to indulge.

Our communities, and our lands are also used to us walking. They say that when children don’t play in the forest, the forest misses them. Likewise, maybe when we don’t walk the land, the land, and the mycelial connections between its people, miss us.

–

If you’d like to explore some of the ideas in this article, or help spruce up the map of hosts, get in touch at rowansalim@gmail.com.

Join us on May 29th for a global zoom call exploring the learning union of guests and hosts, held as part of Giftival.

The line drawings in this article were made by Jan Rymer during the first pilgrimage.

About the Author

Rowan Salim is a learning activist, searching, researching, experimenting with and piloting alternative, grounded and vernacular learning technologies. She’s a walk out from the world international development, aid and mainstream education and has in the last 10 years co-founded Free We Grow, a self directed learning community in South London, helped to establish the Freedom to Learn Network in the UK, and been learning how to learn, grow food, forage, make crafts and forge communities out of diversity in her local neighbourhood through Putney Community Gardens.