by Kū Kahakalau, Ph.D. and Leilani DeMello

“E pū paʻakai kākou” is a Hawaiian saying, which literally means letʻs share some salt together. In traditional Hawaiʻi, it was customary to offer guests, whether family, friends, or a random passerby, food, drink and if desired a place to sleep. “Mai, mai e ʻai!” (Come, come and eat!) was called out to all who approached. When possible, a feast was prepared even for complete strangers and the best one had to offer was shared. When the food was ready, instead of bragging about it, our ancestors said, “e pū paʻakai kākou,” – (letʻs share some salt) since, when there was no food at home when a guest arrived, one offered a least some salt and water to the visitor.

Choosing “E pū paʻakai kākou” as a title for this piece, we intend to reflect on the aim of EA (Education with Aloha) Ecoversity, an innovative post-secondary initiative scheduled for start-up in 2020, particularly to contribute to the re-establishment of food sovereignty in Hawaiʻi by helping learners return to the traditional practice of growing our own food and generously sharing those foods with others. EA Ecoversity is built on over 30 years of Indigenous action research and a culturally-driven Pedagogy of Aloha, which means sovereignty in Hawaiian. Over the decades, EA has been tested and consolidated with thousands of native Hawaiian children, youth and adults on multiple islands and is based on a formula that states Relations + Relevance + Responsibility = Rigor + Fun. EA is grounded in Hawaiian traditional wisdom and knowledge systems, and rooted in the understanding of our Hawaiian ancestors that consider aloha, or love, care and compassion, as the most essential ingredient in education. EA Ecoversity is also part of the emerging Ecoversities Network, an informal global alliance of learners and communities reclaiming diverse knowledges, relationships and imaginaries, to design approaches to higher education that are at once ancient and modern.

As recent as 1778, when Westerners first sighted the Hawaiian islands, Hawaiʻi was 100% self-sufficient, producing adequate amounts of food for a population estimated as high as 1 Million, who managed land and water resources sustainably. In fact, Hawaiians produced everything needed not just to survive, but to thrive. Today, with a population of only a few 100,000 more than in 1778, over 90% of our food is imported from somewhere at least 2000 miles away. This serious food crisis is being addressed by a steadily increasing number of individuals and groups who collectively – and increasingly more collaboratively – are aiming to re-establish food sovereignty throughout the Hawaiian archipelago. These efforts include not only increasing local food production, but more importantly shifting the mindset of Native Hawaiians and other Hawaiʻi residents, as it pertains to the imperative of growing our own food, once again.

This article explores the efforts of EA Ecoversity to contribute to this shift in mindset and the advancement of Hawaiʻiʻs food sovereignty movement, aligning with the goal of the global Ecoversities network, the Hawaiian Independence movement, and attempts of Indigenous people’s worldwide to re-establish a reciprocal relation with earth mother, whom we call Papa in Hawaiian.

According to a Hawaiian cosmogonic genealogy, this relationship goes back to the beginning of time, when earth mother Papa gave birth to a female before giving birth to the islands. Her daughter then gave birth to the first kalo, or taro, our primary staple, as well as the first Hawaiian. This creation story provides the foundation for the traditional, familial, reciprocal relationship between the islands, i.e. the land, the taro and man, with man being responsible to serve and take care of the islands and the taro, so that these older siblings can take care of us.

In pre-Western-contact Hawaiʻi, all food consumed in the islands came from the land and the ocean. These foods were considered kinolau (body forms) of our gods and therefore treated with utmost respect and care. In fact, Hawaiʻiʻs most important law at the time of Western contact was the Aikapu, or Sacred Eating, which included many taboos relating to food, food preparation, eating and disposal of food. There is no doubt that our ancestors understood the value of food and its inherent sacredness. They understood that food did much more than satisfy our hunger and satiate one of our most basic human needs. Food empowers and strengthens, comforts and pacifies, it builds and solidifies relationships. It also enables cultures to transfer deeply held beliefs and traditions. In Hawaiʻi, for example, where eating was highly ritualized, to ʻai kū, which literally means to eat while standing, or to eat without proper reverence and ceremony, was considered a huge transgression against the gods and applied to a person who broke taboos, or did as he wished.

In general, most extended families, called ʻohana, grew their own food on fertile volcanic soil, which allowed planting and harvesting 12 months out of the year. They also raised their own pigs, dogs and chickens and harvested fish, seaweed and other delicacies from the ocean, the rivers and from man-made fishponds. In addition, ʻohana members generously shared food resources with one another, their chiefs, as well as the larger community. In fact, gifting food is still an important value among Hawaiians today, especially among the older generations, with most of us bringing gifts of food when going to someone elseʻs house and our hosts giving us food both while we are there and when we leave.

To assure that there was an abundance of food for all, our Hawaiian ancestors made great efforts to maintain and enhance the well-being of the land and the ocean for the greater good. A traditional Hawaiian proverb states, “He aliʻi ka ʻāina; he kauwā ke kanaka,” which translates to the land is the chief and man is the servant. This proverb can only be understood in the context of the traditional relation between the aliʻi (the chiefs) and the kanaka (the common people), which was a reciprocal relation of aloha (love, compassion) and care. This meant that the chiefs had a responsibility to take care of the people and the people had a responsibility to take care of the chiefs. Those chiefs, remembered as pono, or righteous and honorable, who were deeply revered and cared for by the people, always took good care of the land, the people and the gods. By saying the land is the chief, our ancestors validated that the land takes care of the people and assures our good health, just like a good chief would. Moreover, the proverb implies that we, the people, need to take care of the land, like we traditionally took care of an honorable and righteous chief.

This sacred, reciprocal relationship was irreparably damaged after US missionaries introduced not just a new God, Western laws, and the palapala (reading and writing), but also the concept of private land ownership in the 1840s. Within less than 50 years, this radical change in the reciprocal relation between the land and the people, resulted in the alienation and separations of most Native Hawaiian families from our ancestral lands and over time from the consumption of our traditional foods. At the same time, “ownership” of Hawaiian land was claimed by white foreigners, who quickly transitioned Hawaiʻi from a fully independent gifting economy to one focusing on large-scale export agriculture and the import of new foods.

While the traditional Hawaiian diet resulted, according to early Western eyewitness accounts, in an extremely fit and healthy population and exceptional general health and welfare, the change to a Western diet continues to contribute directly to chronic illnesses like obesity, diabetes and heart disease, rampant among native Hawaiians, which have put us on the bottom of all negative health statistics in Hawaiʻi. This change resulted both from a loss of access to traditional staples like kalo (taro), ʻulu (breadfruit) and ʻuala (sweet potatoes), as a result of Hawaiian alienation from the land, as well as intense pressure to adopt new, primarily North American foods, eating habits and values associated with food.

In addition to new foods and other goods, Hawaiʻiʻs sugar and pineapple plantation owners, many missionary descendants, also imported hundreds of thousands of primary Asian contract laborers in the 1800s, promoting a plantation mentality still affecting the local psyche. This large scale export plantation economy also contributed to a steady decline of locally produced foods. While Hawaiʻi still grew about 60% of itʻs own food in the early 1960s, today only about 10% of our food is produced locally. Indeed, importing food into Hawaiʻi has become a multi-billion dollar a year industry.

Regrettably, depending on 90% of our food delivered from harbors thousands of miles away has put Hawaiʻi into a state of extreme food insecurity and dependency on outside resources. If food shipments from the U.S. were interrupted for any reason, it is estimated that the island of Oʻahu where 80% of Hawaiʻiʻs population resides, would run out of food within three days. While the other six less populated islands might survive a little longer, even there, food would soon become a scarce commodity.

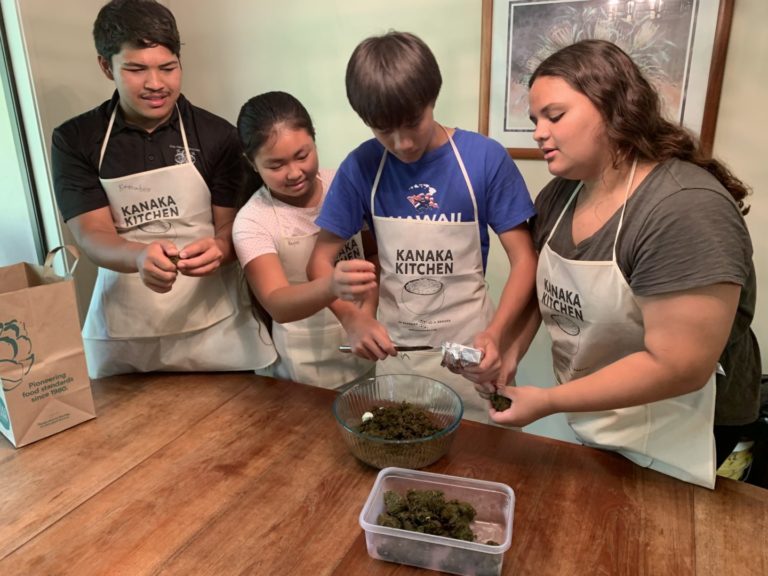

In response to this extreme food insecurity, diverse individuals and organizations throughout Hawaiʻi have been working on growing healthy, organic food on Hawaiian soil, and increasing the amount of fresh produce available at local markets and stores. These initiatives have become even stronger as a result of Covid19 at the time of this writing, showing how our effort in promoting an understanding of our individual and collective responsibility in re-establishing and maintaining a traditional, reciprocal relationship with the land, is something that is still necessary in our contemporary, everyday living. EA Ecoversity encourages learners to consume and share our foods in a way that is culturally appropriate.

The initiative ensures that learners have a solid Hawaiian language and cultural foundation pertaining to food and its relation to health, preparing them to become involved in tackling critical questions on how to recreate traditional agricultural systems and take charge of Hawaiʻiʻs food systems. We do this by studying advocacy efforts to increase local, “grown-here, not flown-here” food production, contribute to the development of policies relating to food sovereignty that reflect Hawaiian knowledge and values, and become involved in politics impacting food production and distribution. This includes fighting to obtain access to land for cultivation that is free of contaminants, as well as demanding land on which a farmer can live on while farming. These aspects are all fundamentals in ensuring support of local farmers and businesses whose mission is to provide nourishing foods, and contribute to a healthy environment and a positive lifestyle in their communities.

EA Ecoversity also hopes to assist in growing the next generation of Hawaiian mahiʻai, or farmers, one of the most challenging, yet rewarding careers. This includes re-learning how to become involved in growing our own food like our ancestors did, and engaging in mahiʻai or food production as a way of life. By familiarizing learners with place, and inviting them to renew their traditional, reciprocal relation to land, EA Ecoversity hopes to entice and convince learners not only to engage in food production for themselves and their families, but also to consider mahiʻai or farming for a living, fully understanding both the economic opportunities, as well as the challenges facing farmers in Hawaiʻi. According to Mahiʻai Match-up winner and EA Ecoversity partner Brandon Lee, “mahiʻai means more than farmer: itʻs about a deep connection with the ʻāina, observing the weather, and understanding the water and resources around us.”

To stimulate a learner’s relationship to the land, involvement in land stewardship and hands-on food production, EA Ecoversity has developed an Aloha ʻĀina (love for the land) Badge, which concentrates on four areas:

- HOʻOʻULU ʻAI (Growing Food) – Learners grow food for personal consumption and gifting

- MĀLAMA ʻĀINA (Take Care of the Land) – Learners are active in hands-on land stewardship

- ALOHA ʻĀINA – (Love for the Land) Learners practice food sustainability and land stewardship, and exhibit Hawaiian patriotism and political activism around food sovereignty

- KIAʻI ʻĀINA – (Protection of the Land) Learners are passionate guardians of the environment

Over a 2-year period, learners engage in the above four areas using Indigenous action-research and hands-on exploration. Once they are ready to demonstrate that they are proficient in these matters, learners prepare for and execute authentic presentations of knowledge, called hōʻike in Hawaiian. These hōʻike can consist of performances, products or projects that involve authentic audiences and have a real-world impact, or significance in our everyday experiences. Using multimedia, learners capture these hōʻike, which are pre-approved by their learning ʻohana, or family of supporters and include them in their Electronic Portfolio. By planning and executing a personalized, authentic demonstration of their practice of hoʻoʻulu ʻai, mālama ʻāina, aloha ʻāina and kiaʻi ʻāina to their audiences, learners publically validate their skills, while at the same time are already teaching others what they have learned.

One of multiple badges offered by EA Ecoversity, Aloha ʻĀina Badge is designed specifically to solidify the relation between learners and ʻāina (environment) and help them build a deep, familial relationship to their place. Aligned with individual passions and interests, the Aloha ʻĀina Badge also provides ongoing personalized opportunities for hands-on interaction with the environment and allows learners to develop ʻike ʻāina or knowledge of the environment, especially as it relates to food production and preparing and consuming healthy, locally sourced foods, including our primary traditional staples. The Aloha ʻĀina Badge is also meant to function as an asset when applying for a wide range of jobs. While the concept of badges and micro credentialing, in general, is still relatively unknown in Hawaiʻi, a 2018 study by UH doctoral students in Education revealed that non-profit employers, as well as younger employers in government, are open to allowing applicants with microcredentials to apply for land management positions, instead of only considering applicants with a Bachelorʻs in Land Conservation or a related field. In our case, the Aloha ʻĀina Badge validates learners specific skills, not just revolving around growing food, but also around distribution, and other systems to circulate these foods to the local consumers.

EA Ecoversityʻs first cohort is scheduled to begin in the fall of 2020, with a small group of learners who are considered at once co-researchers and pilot testers, and who will be actively involved in shaping our instruction, curriculum and assessment model. These learners will be invited to create a personalized learning plan based on their personal, preferred ways of learning. For some, that means tackling the topic of food sovereignty through the use of art, and using different mediums of expression ranging from colored felt pens to watercolor paints, to digital visuals that allow them to share what might not be easily reflected through words alone. EA Ecoversity strongly supports the process of “arting” (a blend of art and writing) as a way to nurture passion and to approach an issue from different perspectives. EA Ecoversity also encourages performing arts, particularly hula (traditional dance), and other ways of learning, knowing and sharing preferred by the learner.

As Hawaiian youth and families face considerable political, economic, social, and cultural barriers as a result of the systemic alienation of Hawaiians from our ancestral lands, culture, language and traditions, it is imperative that we create models of education that embrace a re-awakening of a deep personal connection and strong sense of responsibility to the land. Data clearly confirm, indeed, that westernization and urbanization have resulted in a detrimental disconnect of native Hawaiian ‘ōpio (youth) and their families from the ‘āina (land) that once nurtured a strong and cohesive culture. EA Ecoversity’s goal is to reconnect our people to one another, to the land and the spiritual world by providing both a solid foundation in Hawaiian language and culture, and a sound practice of aloha ʻāina, which includes growing our own food.

By collaborating with individuals, organizations and communities throughout Hawaiʻi, EA Ecoversity wants to contribute to current efforts to increase food security in a sustainable manner, one that respects land and water resources and revives traditional sharing, or gifting practices. In addition, by working not just with existing partners, but enhancing relationships and partnerships throughout the archipelago, EA Ecoversity aims to strengthen the future of subsistence living and sustainable farming and has already partnered with dozens organizations that are at the forefront of culturally-responsible food production. These organizations are excited to share the current work in their respective programs and businesses with EA Ecoversity learners. This includes MAʻO, a local farm operation on the Waiʻanae Coast on the island of Oʻahu, which provides internships and employment to young adults so they can learn how to grow fruits and vegetables, including traditional Hawaiian staples, while concurrently attending college. Specifically, MAʻO involves rural youth in edu-preneurial projects to empower and support youth leadership for a just, healthy, sustainable and resilient community. Moreover, working together with partners from throughout the archipelago and beyond, EA Ecoversity aims to directly contribute to remedying the unnecessary import of fruits and vegetables to Hawaiʻi and instead assist in the growing of more domestically produced, healthy, and sustainably sourced foods.

Just like our aim to re-establish a politically sovereign Hawaiʻi will not be easily achieved, ending Hawaiʻiʻs dependence on outside food is not an easy goal, either. In fact, it may take decades until Hawaiʻi once again reaches food sovereignty. Yet, progress is definitely underway with more and more Hawaiian children, youth and adults every year learning stories, songs, chants and proverbs about our traditional relationship and responsibility to the land and the spiritual world, and exhibiting an increased knowledge of traditional practices of farming and gathering. More and more Hawaiian of all ages are becoming involved in preparing and consuming healthy, locally-sourced foods.

By requiring all learners to become involved in food production, by growing and preparing at least part of the foods they consume on a daily basis, EA Ecoversity hopes to help them re-establish personal connections between the land, the foods we eat and our survival as native peoples. In addition, EA Ecoversity hopes to contribute to the re-establishment of a gift-economy in Hawaiʻi, where we once again generously share salt with one another.

Bio:

Dr. Kū Hinahinakūikahakai Kahakalau is a native Hawaiian educator, researcher, cultural practitioner, grassroots activist, song writer, and expert in Hawaiian language, history and culture. Since the mid 90s Aunty Kū, as she prefers to be called, has led the Hawaiian-focused education movement, creating the first Hawaiian culture-based school within a school, and the first culturally-driven charter school and teacher licensing program. Her latest efforts center around developing EA Ecoversity, a Hawaiian-focused post-secondary program designed to transition Hawaiian youth to happy, culturally-grounded, thriving, responsible global citizens, able to walk comfortably in multiple worlds. EA, which stands for Education with Aloha, also means sovereignty in Hawaiian.

Residents of Hawaiʻi Island, Aunty Kū and her husband Nālei have been active in Hawaiian grassroots struggles for over 35 years, stopping the bombing of the sacred island of Kahoʻolawe, fighting geothermal development and as of late preventing the desecration of Mauna Kea. In 2017, Aunty Kū was the first anti-TMT expert witness on the Mauna Kea Contested Case Hearing and has been teaching classes at Puʻuhonua o Puʻuhuluhulu University sharing her highly successful Pedagogy of Aloha (love/compassion), which promotes the revitalization of Hawaiian values along with Hawaiian language and culture, hands-on learning in the environment, community sustainability, food sovereignty and Hawaiian self-determination in education and beyond.

Since 2015, Aunty Kū has been part of the Ecoversities Alliance, for which she volunteers sitting as active member of its Shepherding Committee, and sharing her knowledge within this global network, reuniting more than 100 initiatives from all over the world engaged in reimagining education.

Leilani DeMello is a Hawaiian woman, mother, and lifelong learner. She works at Kū-A-Kanaka LLC as the Director of Operations, dedicating herself to projects that benefit the Hawaiian people through the advancement of Hawaiian language, culture, and traditions. Leilani lives with her family in verdant ʻŌlaʻa, in the Puna district of Hawaiʻi island. In her free time Leilani enjoys being outdoors working on the land, spending time with her family and friends, and going on adventures